Powerhouses of poetry have visited UW in tribute to one of their own

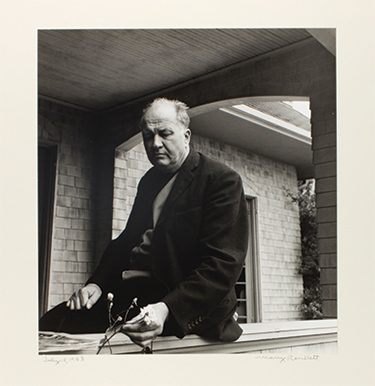

Over the last half century, some of the greatest poets of the English language including John Berryman, Archibald MacLeish and Elizabeth Bishop have come to the UW to perform their own works in the name of Professor Theodore Roethke. Fellow poet, friend and colleague William H. Matchett offers an inside history of the readings.

In the spring of 1963, when Ted Roethke died of a heart attack suddenly while swimming in the Bloedel family’s pool on Bainbridge Island, many friends and admirers from across the country made spontaneous gifts in his memory to the UW Department of English. Robert Heilman, chair of the department, asked Ted’s widow, Beatrice, Professor David Wagoner and me to discuss with him an appropriate use to be made of what was, for then, a generous endowment. We came up with the idea of the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Readings.

In the spring of 1963, when Ted Roethke died of a heart attack suddenly while swimming in the Bloedel family’s pool on Bainbridge Island, many friends and admirers from across the country made spontaneous gifts in his memory to the UW Department of English. Robert Heilman, chair of the department, asked Ted’s widow, Beatrice, Professor David Wagoner and me to discuss with him an appropriate use to be made of what was, for then, a generous endowment. We came up with the idea of the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Readings.

It had been a sad year for American poetry. Besides the loss of Ted, Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams died, as well as Sylvia Plath, who was just reaching prominence. Williams had given a reading at the University just a short time before this, but many other leading poets had not. So we decided to use the fund to bring such poets to the campus while they were still available.

As first established, the readings were a cooperative venture. The honorarium came from the endowment; travel expenses were covered by The Graduate School, and the Department of English provided a reception after each reading, giving the audience a chance to meet the poets and seek autographs. Each poet also had a session the next day with students in the advanced creative writing poetry class.

The first of the readings was set for Thursday, May 25, 1965. Beatrice was touched that we had chosen Ted’s birthday, but that was in fact coincidence. We had merely aimed at the end of the academic year. With his birthday in mind thereafter, we chose the closest Thursday for each subsequent reading.

To open the series, we invited John Crowe Ransom, whom, already in his 80s, we wanted to be sure to include. He gave a fine reading. I especially remember his gusto in presenting “Captain Carpenter.” There was, however, an embarrassing moment. He apparently forgot in whose honor the readings had been established and took the occasion to pay a lengthy tribute to Wallace Stevens, who had died a few years earlier. Ransom was not, however, one of the many poets we had to reassure that we wanted them to read their own poems, not Ted’s.

Though Robert Lowell, the second reader, was considerably younger than the others we invited in those early years, there was a reason for wanting him among the first. Ted tended to think of poetic reputations as a kind of athletic contest. He wanted always to be No. 1 and saw Lowell as his principal competitor. He regularly calculated their relative standing as various reviews were published. There was, you could say, a mixture of admiration and jealousy. Under these circumstances it was a moving occasion to have Lowell come and voice his tribute.

The excitement around these early readings was palpable. Thanks to help from the University’s publicity office, interviews with the poets appeared regularly in the Seattle newspapers as well as on public radio the morning of the reading, which certainly helped to attract an enormous audience. I remember particularly when Archibald MacLeish not only filled the HUB Ballroom but a number of other nearby rooms where equipment was available to broadcast to the overflow.

Once the Roethke Auditorium had been dedicated in Kane Hall in 1972, that became our obvious venue. It was regularly filled, balcony and all. Indeed, when Gary Snyder read in 1976, not only were all seats filled but so, quite illegally, were the aisles. Snyder had a tremendous following among the many Northwest communes of that era, and the odor of marijuana was pervasive in the auditorium.

We had only a few disappointments. Almost a year in advance,

W. H. Auden had accepted our invitation to be the third reader. Some six weeks before the date, however, when I finally managed to reach him by phone, he announced that he “had decided not to come.” I have never seen Bob Heilman so angry; he thought the University had been insulted by Auden’s not bothering to inform us of his change of mind.

Rolfe Humphries was on hand teaching in what was called “the Roethke slot” and, by agreeing at that late date to give the reading, saved us from the embarrassment of having to cancel it.

In 1974, Elizabeth Bishop was the first woman to give the reading. Elizabeth was already popular in our department, where she had twice taught with us in the Roethke slot. Indeed, she was persuaded to give her first public reading anywhere that first time she taught with us.

The “Roethke slot” preceded Ted’s death by some years, referring to the need to find a suitable poet to take over his classes when he was on leave. After his death, with his salary now available, the position became even more attractive and a number of well-established poets, American and British, filled it. In addition to former visiting faculty members, three of the readers were members of our regular faculty: David Wagoner, Colleen McElroy and Heather McHugh.

Our readers in those first years were indeed of the highest caliber. Thinking back now, I recognize that two factors led them to accept our invitations in spite of our modest honorarium. Some came as friends of Ted’s, happy to honor him; others came because they were pleased to be added to so distinguished a company.

Four of the readers had been students of Ted’s: James Wright, David Wagoner, Richard Hugo and Carolyn Kizer. It was one of the strengths of Ted’s teaching that, far from creating disciples who sounded like him, he encouraged young poets to find their own voices. The four we invited were well-acquainted colleagues, but none of them sounded like Ted or like each other. Twice it was a particular delight when, between accepting the invitation and giving the reading, Kizer and Wright each received Pulitzer Prizes.

Wright was happy indeed to be back in Seattle and spent the morning of his reading in the halls of Padelford hunting up faculty members he remembered. Having run into a colleague, he got into the elevator with him to continue their encounter, not interrupting an anecdote that unfortunately included a racially offensive word. An outraged Black student in the elevator swung at Jim with a hard right to the jaw. The student might have appreciated the point of the anecdote, had he heard it in full, but he heard only the offensive word. Jim spent that afternoon writing a poem of apology, which he read that evening.

John Berryman, who read in 1969, proved difficult to handle. No sooner had I met him at SeaTac Wednesday evening than he wanted me to take him to buy a bottle of whiskey. I proposed instead a meeting with some of our better student poets. I knew that, at that moment, a crew was at Paul Hunter’s house collating copies of the latest issue of Consumption, a little magazine they edited. I knew also that they would probably be drinking beer—certainly not whiskey—and that Berryman would very likely find Paul’s conversation stimulating.

It worked beautifully. Berryman spent the rest of that evening talking with Paul in his kitchen and I was able to deliver him to his hotel still sober.

The next day was more difficult. While I had classes to meet, a member of the publicity office agreed to shepherd Berryman to interviews and to show him the sights of Seattle. She called for help in the early afternoon, however, finding it difficult to keep him out of bars. I took over again and stayed with him through supper, delivering him to David, who was to introduce him, in time for the reading.

David knew nothing of what had been going on for the preceding 24 hours, so was caught off guard when, just as he was rising to introduce him, Berryman whispered, “I think I will dedicate this reading to Paul Hunter.” “But,” protested a startled David, “it is the Roethke Reading.” “Oh, yes,” said Berryman and fortunately dropped that idea. Berryman was able, even when intoxicated, to give an astonishingly well-controlled reading.

From 1965 through 1997, the readings were recorded. These tapes, some of which are now lost, are scattered through various Suzzallo collections.

With the exception of Robert Penn Warren’s reading in 1968 and Richard Wilbur’s in 1971, I am happy to take credit for handling the first 25 readings—those through Adrienne Rich in 1988. But the series had gradually been hitting hard times.

When we invited John Ciardi sometime in the 1970s, he responded that he only read for a fee of $5,000. Though there had been additions to the Roethke fund over the years, it could not support a figure like that. Many major poets demanded fees beyond the fund’s means. The Graduate School stopped underwriting the transportation costs, leaving the English Department to cover both those and the reception.

Without the help of different campus partners, the readings have been much less widely announced and what was considered a cultural event for the University and for Seattle has now been reduced to a departmental focus. Sadly, no reading at all was offered in 2017. The money was simply not available. However, things looked up again in 2018 when, despite late publicity, Charles Simic gave what was called the 54th annual reading to a large and enthusiastic audience.

There is every intention to keep presenting readings, but the word “Annual” will probably have to be dropped.