Research creates deep bonds between faculty, students

While research expands knowledge, it also forges bonds between professors and students that can't be broken by fires, disabilities or even death.

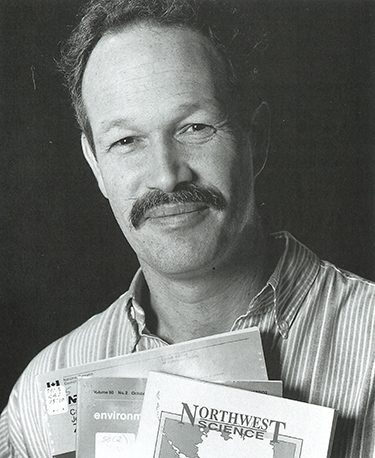

Fisheries Professor Tom Quinn holds the three research journal’s with his late-student’s research papers. Photo by Mary Levin.

John T. Konecki had it made. On the quiet Sunday afternoon of Sept. 11, 1992, the 42-year-old UW graduate student-coffee lover-gadget maker was at the controls of his own plane, a Cessna 170 he named Felix, flying over the San Juan Islands. The woman he loved, his wife Susan, 39, was at his side. Two of his best friends, Sarah and Richard Hacker, both 52, were in the back seat. They were headed for a hiking trip on Lopez Island.

It was a flight Konecki could probably do in his sleep, he had done it so often. The plane was approaching jagged cliffs on the edge of the island, into the typically gusting winds that sweep up the Strait of Juan de Fuca. But this time, wind shear thrashed the little plane, causing Felix to sputter and stall. It went into a nose-dive, plunging 1,500 feet down like a bullet, into an open field. The foursome was killed instantly, just a quarter of a mile from the airstrip.

The news devastated the foursome’s many friends. Tom Quinn was one of them.

Konecki was studying fisheries science at the University of Washington. Quinn, who was about the same age, was his professor, adviser — and good friend. They had flown together to Oregon and Alaska, dined with each other’s families, worked on research projects together. Quinn was pleased and proud that an older graduate student like Konecki was close to earning his Ph.D. after spending years studying the effects of temperatures on Coho salmon.

Before the shock of the tragedy began to wear off, Quinn knew instinctively what he had to do: publish the three research papers Konecki was working on at the time of his death. It was a daunting task, taking over someone else’s sweat, research, experiments, data, intuition and findings and make them publication-worthy. But Quinn never hesitated. “I knew it was a big deal for him to go back to school at his age,” Quinn says, “and I knew his family was aware of him pursuing his dream. It was the right thing to do.” So he contacted Konecki’s mother, back in Maine, as well as the agencies and foundations that sponsored Konecki’s research. “I made a promise that I would publish his work,” Quinn says.

He had little idea what was in store. Konecki’s data — computer disks, papers, files — were all over the place: at his Vashon Island home, in his car, in his lab at the Fisheries Building on the UW campus, at a lab near Hood Canal. Moreover, despite years of meticulous data collection, Konecki had not started writing any manuscripts. Quinn first had to figure out what Konecki had, hire a helper to painstakingly reconstruct what there was, then work up detailed, scientific research papers worthy of peer-review journals. It was like working in the dark.

But in the spring of 1995 came the light at the end of the tunnel: Three different journals accepted for publication the works of the first author, the late John T. Konecki.

“There was no question I was going to see this through,” says Quinn, a UW professor for the past 11 years and, not surprisingly, a winner of a UW Distinguished Teaching Award. “I had to follow through for him.”

Quinn’s devotion to his former student is just one example of the personal research relationships between professors and their students—graduate and undergraduate—at the UW. While the academic stereotype portrays high-paid, aloof professors treating their research students as go-fers who get little recognition, more often faculty and students work together and learn from each other during their course of discovery.

Sometimes it is a disaster that illuminates these relationships. Last March, Zoology Professor Joel Kingsolver and his students were stunned when a fire completely destroyed their fifth-floor lab in Kincaid Hall. The blaze consumed an invaluable butterfly collection, a lab full of equipment, and data and chemicals belonging to his graduate students.

Kingsolver, a renowned authority in his field, not only had to deal with the loss of his priceless collection but the disruption of his students’ works and lives. “The lab looked like a bomb had exploded in there,” Kingsolver recalls. “It was devastating because it brought things to a dead stop.”

There was some good news—the fire only wiped out his lab, not his office or other facilities where some data was stored. And he and his students had saved copies of their research work elsewhere on campus. Still, his three grad students lost valuable information, had no place to work, and were quite shaken. The department was quick to come to everyone’s aid, offering emergency lab space so his students could go on with their work. But Art Woods, a fifth-year Ph.D. student on the cusp of finishing his thesis, was forced to delay completion for a few months.

Replacing the lab, equipment and collections would come in time. But what about everyone’s psyches? Kingsolver made sure to have lunch with his students every day following the fire. “I’m not one who is buddy-buddy with his students,” he says. “But we had to learn to deal with this and what it meant. We talked about what a shock it was, how people felt about it.”

Kingsolver also had students over to his Ravenna home for dinner and more heart-to-heart talks. “There were a lot of hugs and tears,” he says. “In a way, it pulled us together.”

A year later, the lab is rebuilt, and life has pretty much returned to normal. “The support Joel gave us meant a lot,” says Woods, who will be leaving for a postdoctoral assignment at Arizona State University. “We had a lot of fears that we would be blamed for disrupting much of the department’s research. But it wasn’t the case at all. The support we got from Joel and the other professors made the difference.”

UW professors aren’t just making a big difference to graduate students. Currently, 24 percent of graduating seniors report having had some experience in research at the UW. Since he took the helm in 1995, President Richard L. McCormick has emphasized the need to involve more undergraduates in research.

While the emphasis is relatively new, undergrads have been involved in research for years. For instance, a summer program supported by the NASA Space Grant Program, the Mary Gates Foundation and faculty research grants has given practical science experience for 176 undergraduates since it began in 1993. Four undergraduates recently accompanied two geography professors for a 17-day cruise between Seattle and Hawaii to study subtropical oceans and how they absorb greenhouse gasses.

David Salesin. Photo by Mary Levin.

David Salesin, a professor of computer science and engineering, is well known for regularly involving undergraduates in his cutting-edge research projects and having them co-author papers in prestigious journals.

“I try to get undergraduates involved in every part of the research process, from planning to implementing what we do, to collecting the results and writing and presenting the papers,” Salesin says. “They’re a huge part of this success.” The success is phenomenal. Salesin who joined the UW faculty in 1992 and is also a winner of the UW Distinguished Teaching Award, had an astonishing total of eight papers accepted for publication at a 1996 conference. Four were co-authored by undergraduates.

“Having facts and information is useful, but the idea of research is really the discovery process,” says Robert Steiner, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the UW School of Medicine, who has included undergrads in his work for 20 years. Steiner won a UW Distinguished Teaching Award in 1996.

While the University is renowned for its world-class research and attracts more research money from the federal government than any other public institution in the U.S., this kind of research power has its detractors. Critics say faculty concentrate more on research than undergraduate students.

“I want a student who completes a degree at the University of Washington not only to have heard lectures from faculty who are outstanding in research and other practices but to have an opportunity to engage with them in area of their work,” McCormick recently said in an address to the University community.

With these opportunities to discover and disseminate knowledge come the special relationships between professors and their students.

One person who benefited from a personal relationship was Mike Hutnak. He had come to the UW after attending Washington State University for three years before running out of money. “Typical college gig,” he says. “It was the Reagan era. I couldn’t get any more financial aid, and my choices were either to work and save my money for school or work full-time and go to school full-time. I decided to work.”

For five years, he ran pizza joints in Pullman and Moscow, Idaho. When he saved up enough money, he decided he had tired of studying biology at WSU, and came to the UW in 1994 to try his hand at geological oceanography. When he heard that Oceanography Professor H. Paul Johnson needed help in his lab, Hutnak, a junior, jumped at it, even though he had little experience in the field.

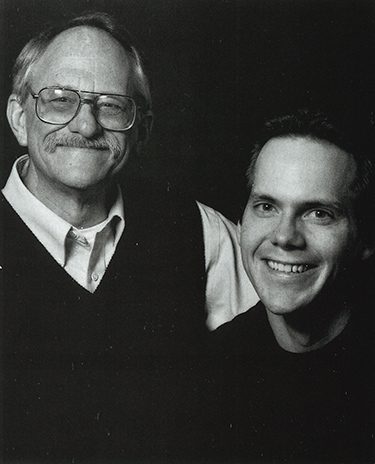

Oceanography Professor H. Paul Johnson stands beside undergraduate research student Mike Hutnak. Photo by Mary Levin.

Right from the start, he got involved in some of Johnson’s biggest projects funded by the National Science Foundation, including trying to measure heat flow in ocean sediments. Hutnak was no “test-tube washer.” He single-handedly devised and built an instrument made out of nylon, padding and electronic thermometers that measured both sea temperature and heat emanating from the ocean floor’s rock surface.

“I just turned him loose,” says Johnson. “He did all the design, construction and testing, and was so successful, the Japanese asked him to build one for them. And he did.”

The success of the project — funded by a special NSF Small Grant for Exploratory Research for “crazy ideas,” Johnson says — could lead to a follow-up $1 million grant.

Hutnak’s work helped record the first-ever measurements of heat coming from bare rocks near seafloor volcanoes. Scientists are using this data to create computer models of the heat coming from deep within the Earth.

“At first, I felt in over my head,” recalls Hutnak. “Grad students have sound footing on theory and a background of looking at a particular problem. They are also taught to think in a different way. But I was able to come into Paul’s office at any time to ask questions, go over things, go get a bite and work things out.”

Why was such a respected oceanographer so open to working with a junior with no background in the field? “I don’t work well talking to myself,” Johnson says. “Students here are not passive receptors. They make major contributions. This is not a government or industrial lab, after all. And he had the initiative and maturity to make it happen. I found that inspiring, and I learned a lot from him.”

Hutnak, who received his bachelor’s degree in 1996, is still around. Shortly after graduation, he was hired as a technician in Johnson’s lab, despite his lack of graduate training. “The support and encouragement I got from Paul and the department is what got me here,” Hutnak says. “We worked almost as peers, on the same level. I am given very important tasks, even ones I don’t know completely. I take it upon myself to learn a computer program, for example, and see how it fits into our projects.”

Li-wei He, a 22-year-old native of China, had the same undergraduate experience in computer science. “Usually undergraduates are hired to do simple programming, but we have helped lead the research,” says He, who helped Salesin and Michael Cohen at Microsoft Research develop “virtual cinematography software.” The program provides movie-like video representations of on-line chat worlds in real time.

Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh, a professor of botany, is another believer in the benefits of undergraduate research. “Research experience is a better way to learn than just taking a course,” she says. “Once students have hands-on experience, they will want to read and study about the subject—and not just so they can pass a test. Research can excite people.”

Yet there is a flip side to having undergrads working in the lab, she points out.

“Having undergraduates involved in research is very time-consuming, inefficient, and will almost never yield publishable results,” she admits, adding that in her field, it is difficult for students just starting out in college to have the background to make significant contributions in the scholarly press. With pressure on faculty to publish, often there isn’t much time to bring new students to a higher level.

Botany Professor Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh (right) and her partially sighted student, Anne Prather. Photo by Mary Levin.

When Van Volkenburgh first heard McCormick’s directive for undergraduate research, she wondered what kind of impact it would have on programs like hers. “I sometimes feel I don’t spend enough time with undergraduates as it is, and when they are involved in research, they sometimes need hand-holding or explicit direction. That takes extra time and effort,” she says.

And with the pressure to win grants and achieve significant results from research projects, she wonders if it would be better to have her graduate or postdoctoral students supervise undergraduates. “Having undergrads involved in research is a terrific teaching tool,” she says, “but we also need to spend time and energy getting grants to fund our labs.”

But there are benefits as well. “There is no denying that a research group does well to have young and old members. Young students ask naive questions—and many times, they are the most astute questions. It is very revealing.”

She and her undergraduate research students have had some wonderful success stories. For example, there was the case of a student who was interested in becoming a teacher. She proposed developing botany experiments for high school biology classes. Van Volkenburgh and her student interviewed a Seattle high school teacher and found that it was too just difficult to mass produce enough experiments for a high school class.

“The project worked absolutely beautifully,” Van Volkenburgh says. “The student came up with the idea and I just helped her when she needed it. The best part was we were able to present our findings to an audience of national high school teachers. It was a valuable, hands-on experience, and we were able to make something very important of the results. That’s what counts.”

So was the relationship she developed with another student, Anne Prather, a legally blind post-baccalaureate researcher.

A year and a half ago, Prather was in Van Volkenburgh’s plant physiology class when she asked to participate in research activity. At first, Van Volkenburgh was worried that Prather’s inability to see would prevent her from making significant research contributions. Van Volkenburgh had not worked with sightless people before. But she was surprised. Prather, who used a Mary Gates Fellowship grant to purchase a special microscope for sightless people, has had a positive impact on research efforts.

Prather, who is interested in genetics, has built a strong relationship with Van Volkenburgh, who knows less about it. “She is teaching me about genetics and how to work with people with disabilities. She is a wonderful person to work with, and I am learning from her a very different learning style. She encounters barriers but I encourage her to go on. I am inspired watching her deal with challenges, and that is rewarding,” says the botany professor.

Adds Quinn: “Building good relationships with students is meaningful not in just what you can produce in terms of research, but because the both of you can learn so much. You get to share, you get to learn. And that is what it is all about.”