Research tests how to put the squeeze on fruity drinks

Fruit drinks are often disguised as nutritious alternatives to soda. But in reality, many have added sugar that can increase the risk for obesity and tooth decay, especially in children. To counter this, a team of UW researchers and colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study about messaging around the sugar-sweetened drinks and then crafted a campaign to reach parents with facts that will help them make healthy decisions for their families.

The study set out to assess the effect of culturally tailored countermarketing messages on drink choices, similar to stark anti-smoking campaigns. It involved more than 1,600 Latinx parents who participated by joining Facebook groups. Study authors focused on this demographic because Latinx children have a high rate of sugary drink consumption, and the beverage industry intentionally targets the Latinx community, says James Krieger, lead author and clinical professor of health systems and population health in the School of Public Health.

“The negative health effects associated with the consumption of sugary drinks—such as tooth decay or, later in life, diabetes—are disproportionately affecting this community,” Krieger says. “We want these and other kids to be able to avoid developing strong taste preferences for a product that’s ultimately going to harm them.”

To design their study, which was published in the American Journal of Public Health, the researchers consulted focus groups involving Latinx parents from across the country to get their perceptions of how marketing works, how they think about what they are buying for their children and how to culturally tailor messages that would resonate in their community.

“They know that targeted marketing happens all the time in the digital era, but what really got them was the fact that they were given deceptive information that they felt was leading them to make unhealthy choices on behalf of their kids,” Krieger says.

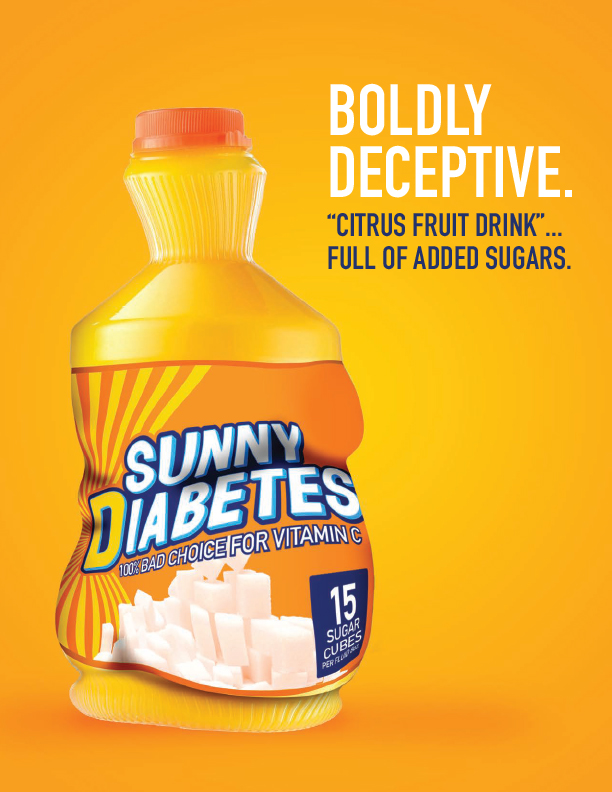

That industry marketing, Krieger adds, led parents to believe fruit drinks are healthy beverages by creating a “halo of health” around the product. Ads, labels and even online games and cartoons often contain claims about nutrients such as vitamin C and images of healthy kids drinking fruit drinks while participating in sports.

Working with a Latinx marketing firm, the researchers created countermarketing graphics and messages in Spanish and English designed to elicit outrage, fear of the harmful effects on children and other negative emotions. The messages, which can be found at truthaboutfruitdrinks.com, call out specific brands and images as well as the adverse effects of these products. “We looked at anti-tobacco messages and the words and types of images they used,” Krieger says. “We wanted messages that would appeal to folks on an emotional level as well as a cognitive one, because that’s what research shows drives people to make choices.”