Scholarship honors tunnel creator John Arthur Elliott

For centuries the Cascade Mountain Range was a formidable barrier between the Pacific Ocean and the eastern inland. Until the 1910s, the only access was by way of footpaths, railroads or the Columbia River, a daunting waterway hosting turbulent rapids, landslides and sheer rocky cliffs. As cars and trucks became more common, it became clear that a highway was needed.

For centuries the Cascade Mountain Range was a formidable barrier between the Pacific Ocean and the eastern inland. Until the 1910s, the only access was by way of footpaths, railroads or the Columbia River, a daunting waterway hosting turbulent rapids, landslides and sheer rocky cliffs. As cars and trucks became more common, it became clear that a highway was needed.

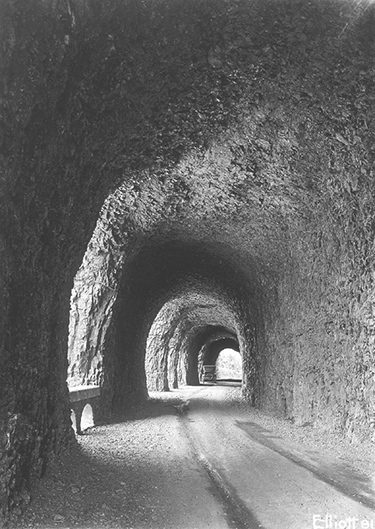

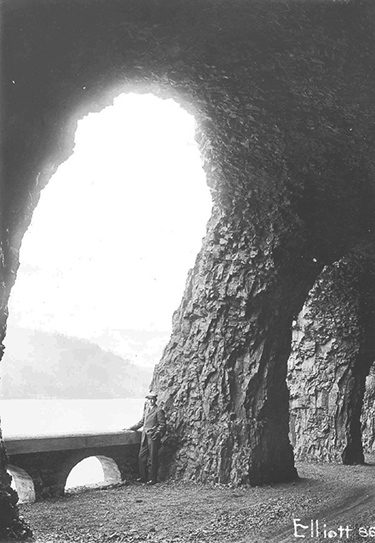

John Arthur Elliott, ’09, ’29, an engineer for the Columbia River Highway construction project, was charged with identifying the least obtrusive way to open the country’s scenic beauty to motor travelers. Elliott was inspired by a photo of a tunnel in Lucerne, Switzerland, which had four windows looking out on Lake Uri and the Alps, and he thought a similar design could be used along Mitchell Point, a prominent cliff on the Columbia River’s edge. But building a tunnel carved entirely from the riverbank’s natural cliff presented a huge engineering challenge. Contractors with years of experience would have no part of the project.

Elliott forged ahead with support from the Oregon State Highway Commission and the U.S. Geological Service and completed the tunnel in eight months. The finished product had five arched windows through which travelers could see the flowing Columbia River and-on clear days-the snowy peaks of Mount St. Helens and Mount Rainier. The Mitchell Point Tunnel was both a feat of engineering and a work of art.

It was also the focus of family fun for Elliott’s daughter Marjorie Elliott Bevlin. “A favorite Sunday outing was to take a picnic lunch up the highway and eat it by a stream or waterfall, and then go on and visit Daddy’s tunnel,” she says.

It was also the focus of family fun for Elliott’s daughter Marjorie Elliott Bevlin. “A favorite Sunday outing was to take a picnic lunch up the highway and eat it by a stream or waterfall, and then go on and visit Daddy’s tunnel,” she says.

The tunnel served as a primary car and truck route along the Columbia until 1932, when Tooth Rock Tunnel was opened, offering an alternative route. In the 1950s Interstate Highway 84 was built for heavier traffic, and the narrow Mitchell Point Tunnel was permanently closed. State officials began to worry about the potential hazard of rock from the tunnel falling onto the highway below, and in 1966, 10 years after Elliott’s death, contractors blasted the tunnel from the face of the cliff.

Although the tunnel is gone, Elliott’s legacy lives on. To honor her father’s accomplishments Bevlin has named the UW Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering as a beneficiary of her life insurance plan. The future gift will establish an endowed scholarship in John Arthur Elliott’s name. The scholarship will be awarded to undergraduate students who share Elliott’s awareness that engineering can improve function as well as nurture the spirit.