Snickering aside, author Bryn Nelson, ’98, sees treasure in human waste

When he was 10, Bryn Nelson wanted to grow up to be a veterinarian. The Minnesota boy loved his cat, Smokey, and his dog, Heather, and catching and releasing frogs. He did not dream his penchant for pets would lead him to study microscopic life forms and author a 432-page book about human feces. He followed his love for animals and science to become both a microbiologist and a writer.

When he was 10, Bryn Nelson wanted to grow up to be a veterinarian. The Minnesota boy loved his cat, Smokey, and his dog, Heather, and catching and releasing frogs. He did not dream his penchant for pets would lead him to study microscopic life forms and author a 432-page book about human feces. He followed his love for animals and science to become both a microbiologist and a writer.

Nelson, ’98, became a scientist first. After his junior year at Concordia College, he spent the summer inside a fly genetics laboratory at the Baylor College of Medicine. That experience and an older brother already in grad school primed Nelson as he headed for graduate studies at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Partway through his doctorate at the School of Medicine, he heard about a science writing master’s degree at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He met someone who attended, and grilled them to make sure this was the right path. He started writing about science for The Daily to build up clips.

Now “there’s certainly much more awareness of alternative careers, but at the time there wasn’t,” he says. At the time, students could either do postdoctoral research and hope to someday have their own labs at research universities, or they could work for industry. Neither was for him.

His expertise in science writing turned out to be a golden ticket. Nelson completed two internships with Newsday and eventually was offered a full-time job. In the heyday of science coverage, the newspaper would fly him to space shuttle launches and news events about cloning. He worked with a photographer and graphic designer for big print projects. Then, with the downturn of the newspaper industry, he shifted to freelance work and moved to Seattle from Brooklyn with his husband-to-be.

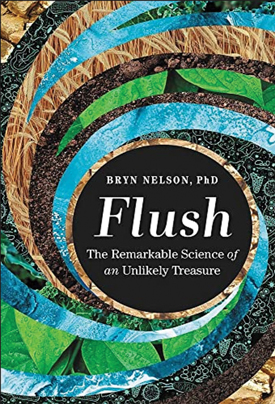

Nelson’s new book, “Flush: The Remarkable Science of an Unlikely Treasure,” began with him researching a magazine article on fecal transplants. Fecal transplants are the donation of one person’s waste into another person’s gastrointestinal tract to restore a balance of gut microbes. This is an effective treatment for some patients with a runaway infection from Clostridium difficile, or C. diff, one kind of gut bacteria that causes severe diarrhea and can be fatal. Treatment with antibiotics is often not effective.

In 2014, when Nelson wrote a magazine story about a woman who almost died from a C. diff infection, he became fascinated with how our cultural disgust with feces might have delayed the medical community from fully accepting the value of fecal transplants in certain cases. Such transplants are much more widely practiced now. In September, the Food and Drug Administration gave committee approval for a fecal transplant product prepared by Ferring Pharmaceutical.

“It was this rapid evolution of something from this kind of laughed-at folk remedy essentially into something saving lives and vastly outperforming antibiotics,” Nelson says. “That got me thinking about other potential uses.”

In his book, different chapters identify ways that human waste can serve as a resource that returns clean water to a community, or fertilizes agricultural land, or helps an environmentally responsible building stay green. The circular economy for human waste offers approaches for some of the challenges of climate change. To give just one example, recycling water from urine and feces is a way to restore drinking water to California areas that are dependent on the Colorado River.

“Eventually, I was able to find an agent,” Nelson says, for what he calls his quirky topic. His book was published in September and has been reviewed by news outlets including The New York Times. That review, by Elizabeth Royte, calls Nelson “irrepressibly curious, prone to punning and incapable of embarrassment.” He “examined his stool daily for a year, using three apps that tracked frequency, speed of transit, quantity, consistency and color.”

Nelson does bring a scientist’s zeal for detail to all that he examines in the book. That includes his own waste as well as studies of the waste of thousands of other humans.