The best of 1991: Teaching and public service awards

Traditionally, June is the month when the UW and its alumni association announce the winners of the annual teaching and public service awards. This year there are eight exceptional people and one famous organization that have contributed greatly to the University’s teaching and public service missions. Brief profiles of the winners follow.

Stephen Woods

Stephen Woods has “students” who aren’t even his students.

Stephen Woods has “students” who aren’t even his students.

“There are two kinds of teaching,” explains the 49-year-old professor of psychology and winner of a 1991 Distinguished Teaching Award. The first is classroom teaching. “I try to make lectures interesting with content that relates to students’ everyday lives,” he notes.

But it’s the second kind of teaching, serving as an “informal counselor of sons,” that “perhaps I’m proudest of,” says Woods. He devotes liberal amounts of out-of-classroom time to help students—from “freshmen through doctoral candidates”—discover what they want to do and what they want to get out of life. In many cases, the students who accept his well-publicized invitation to drop by and talk are not taking his classes.

As one graduate student said, “I hope I can adequately describe the seemingly magical way Dr. Woods can make almost any individual feel immediately comfortable with him as a person.”

Born in Pasadena, Calif., Woods moved to Olympia when he was in the eighth grade. He received UW undergraduate degrees in zoology and psychology in 1965 and 1966, respectively, and earned a Ph.D. in psychology and physiology, also from the UW, in 1970. After two years as an assistant professor at Columbia University, he joined this faculty in 1972.

Also an adjunct professor of medicine, Woods teaches in a range of situations from 100-level lectures with up to 700 students to “Surgical and Histological Techniques,” an intensive course for would-be physicians and animal specialists.

He also teaches “Survival Skills in Academia,” a highly praised course drawing on his own experience as chairman of the department from 1981 to 1988.

Woods has developed a course on the psychobiology of human eating which relates to his major research focus: human eating and eating disorders. He and his research team have found that the insulin levels in the brains of rats and baboons are instrumental in monitoring and controlling appetite. If it turns out that humans respond in similar ways, the research may eventually help both the obese and the very underweight, such as anorexia nervosa sufferers.

Thomas Quinn

When Thomas Quinn was a graduate student at the University of Washington, one of his professors told him, “If you really want to be in academics, you should be willing to give your best ideas away.”

When Thomas Quinn was a graduate student at the University of Washington, one of his professors told him, “If you really want to be in academics, you should be willing to give your best ideas away.”

Quinn has followed that advice, giving away not only his best ideas, but sharing his skills as a teacher in the School of Fisheries. A winner of the 1991 Distinguished Teaching Award, the associate professor teaches a basic course in fishery ecology to both undergraduate and graduate students, as well as a graduate level course in his specialty—salmon and trout ecology and behavior.

His philosophy of teaching is simple. “I try to treat them like colleagues rather than like underlings,” he says of his students. “If I get a good idea, they are the first ones I bring it to.” These research ideas may get dropped by the student, but often, he reports, “They do a better job than I could.”

This kind of encouragement fosters an ideal environment for learning.

“Many students volunteer to go beyond the original work assignments,” reports one woman graduate. The 37-year-old Quinn is also well known for his field trips.

A native of New York City, Quinn says he learned the basics of teaching from his parents, who were both English teachers in the City College of New York system. His itch for ichthyology was the result of a third grade teacher’s fish tank. “She let me take care of the fish,” he recalls, and soon he was hooked. “My parents bought me a tank, and then some books about fish, and then more tanks and more books.”

After getting his B.A. at Swarthmore College, Quinn came to one of the best fishery schools in the nation—the University of Washington. Here too he encountered good teaching, citing Zoology Professor Gordon Orians as “the best teacher I had here.” He earned an M.S. and Ph.D. at the UW in 1978 and 1981 respectively, and then spent four years doing postdoctoral work in Canada before he returned to teach in 1986.

Quinn discounts the prejudice that some say big research universities have against teaching. “When I came up for tenure, the message was clear. It was considered very important.”

For Quinn, it is an importance he will continue to foster. He rejects what he calls “a class society” in education. “When we work well with students, we break down the barriers.”

Samuel Wineburg

Teaching is the only profession with a 13,000-hour apprenticeship, notes Educational Psychology Assistant Professor Samuel Wineburg. “Teacher education begins the first day you go to kindergarten.”

Teaching is the only profession with a 13,000-hour apprenticeship, notes Educational Psychology Assistant Professor Samuel Wineburg. “Teacher education begins the first day you go to kindergarten.”

In the typical apprenticeship, the student follows the master through case studies, such as a physician on rounds or an intern at a newspaper. But in those 13,000 hours of grade school, middle school and high school, a student is never “taken behind the wings, never shown the teaching decision-making process,” notes this winner of a 1991 Distinguished Teaching Award.

When his own students walk through the classroom door to attend an introduction to educational psychology course, Wineburg takes them behind the lectern in surprising and innovative ways. He is famous for his ruse on the first day of class. A pseudo-professor presents himself as Wineburg and stans the session with a pop quiz and a jargon-filled lecture. Wineburg, masquerading as a student, asks the professor to “please stop and explain this.”

The other students are usually aghast, as Wineburg presses the fake professor. “I’m the only one who is saying ‘Help,'” he notes. When the ruse is revealed, Wineburg spends the rest of the time analyzing the students’ attitudes, particularly their tendency toward apathy in the face of insufficient teaching.

Wineburg refuses to use a textbook. He spends hours preparing for each lecture, looking for simulations, metaphors and other techniques to illustrate his point. On an “off” day, he will even stop the class to analyze his own mistakes in teaching.

The effect on his students is indelible. “A psychology student sat in his class by mistake, but wanted to stay because he found Sam the best teacher he had seen in his four years at Washington,” reports Education Dean Allen Glenn.

The 33-year-old Wineburg is a native of Utica, N.Y. He spent his undergraduate years at Brown and Cal-Berkeley, and then taught remedial reading for two years at an inner city school near Oakland, Calif. Wineburg got his Ph.D. from Stanford in 1989, the same year he came to the UW.

Tsianina Lomawaima

Somehow, in the crush and confusion as thousands of graduates lined up for the 1990 commencement exercises, Tsianina Lomawaima and her Native American students found each other.

Somehow, in the crush and confusion as thousands of graduates lined up for the 1990 commencement exercises, Tsianina Lomawaima and her Native American students found each other.

It was all “pretty miraculous” considering the number of participants, says the assistant professor of anthropology and winner of a 1991 Distinguished Teaching Award. Lomawaima, herself a Native American, served as a marshal at both sessions of commencement. “Somehow, the American Indian graduates found me and we all walked in together,” she recalls.

Helping Native American students achieve a sense of “place” in the classroom is an important influence on her teaching. “It’s not the curriculum content alone, but the way classes are run, the way people interact with the rules,” she notes. “What are the rules for being a good student? For being a good teacher? The challenge of diversity is how to open up those rules.”

She starts by “just telling people they have a right to be here,” a message she appreciated receiving from her colleagues when she began her UW teaching career three years ago. “It’s a very simple message but it doesn’t get said as often as it should.”

Next comes developing the writing and speaking skills the academic environment demands. It’s hard work but Lomawaima discourages excuses. “It’s easy to say, ‘It’s all somebody else’s fault, poor me,'” she notes.

Lomawaima has developed four new courses at the UW. She’s also a popular guest lecturer in courses taught by other faculty.

Born in Kansas City, Kansas, in 1955, Lomawaima earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology at the University of Arizona as a National Merit Scholar. She received her master’s and Ph.D. from Stanford University. She is currently conducting research on the history of Native American education.

Betty Jane Narver

The winner of the University’s Outstanding Public Service Award almost single-handedly saved a public affairs league from certain death, coauthored a landmark series about growth that appeared in the Seattle Times and last fall spent four months in an Ethiopian village teaching agricultural practices to the subsistence farmers.

The winner of the University’s Outstanding Public Service Award almost single-handedly saved a public affairs league from certain death, coauthored a landmark series about growth that appeared in the Seattle Times and last fall spent four months in an Ethiopian village teaching agricultural practices to the subsistence farmers.

And Betty Jane Narver did all this while running the Institute for Public Policy and Management in the UW Graduate School of Public Affairs. On the staff of the institute since 1975, Narver has been a catalyst for change on such vital issues as education, growth and economic vitality.

“It’s a seamless life,” she says. “I see no distinction between the work I do here at the UW and the work outside.”

One secret of Narver’s success is “her truly amazing capacity to see connections between and among people, and her willingness to generously reach out to all of them,” says Public Affairs Dean Margaret Gordon.

Perhaps her most remarkable feat was to bring the Municipal League of King County back to life—after most political wags had tagged the nonpartisan organization as terminal. The league’s coffers were empty and its director was removed when Narver took over as chair of the league’s board in 1988. Narver helped find a new director, set a new direction for the league and was critical in raising more than $100,000 to support the rebuilding. “There would be no Municipal League today if it were not for Betty Jane Narver,” wrote the current league leaders, Joseph McGavick and Cynthia Curreri.

One of the issues that the revived league addressed was the problem of growth in the Puget Sound region, at a time when “it was not perceived as a really central issue,” Narver recalls. When the Seattle Times hired Neil Peirce to write a series on growth, he turned to Narver as a guide. They worked so well together that he invited her to co-author the series.

The 56-year-old Narver also made the personal commitment of spending last fall in the village of Godina, Ethiopia, where she worked on a Plowshares agricultural project. The group tried to encourage farmers to diversify their crops and to include more vegetables in their diets.

Narver says her commitment to public service comes as no surprise.

“I grew up in a family where a lot of attention was paid to public service, politics and the civic life,” she says.

She got her B.A. from Mills College in 1956 and worked in such varied settings as a reformatory in Pennsylvania and as a Congressional assistant. She earned a master’s degree in Asian languages and literature at the UW. She entered public affairs through volunteer work at her children’s schools.

Looking ahead, Narver sees integration of social services and education as one of the coming challenges facing our society. She admits the problems are great, but remains optimistic. “I have to be. Anyone who is energetic has to be an optimist or it’s all over. I work very hard, and I feel there are ways things can be changed.”

Betty Kramer

“I’ve always wanted to go into social work,” says Betty Kramer, a social work teaching assistant who won a 1991 Excellence in Teaching Award. “I really enjoy people and I want to be in a profession that allows me to work with others in a meaningful way.”

“I’ve always wanted to go into social work,” says Betty Kramer, a social work teaching assistant who won a 1991 Excellence in Teaching Award. “I really enjoy people and I want to be in a profession that allows me to work with others in a meaningful way.”

At first Kramer dedicated herself to older Americans by working at hospitals, nursing homes and social service agencies. But after earning a bachelor’s and a master’s in the Midwest, she came to the University of Washington to earn a Ph.D. and to teach others human service practice skills.

After being a TA in several courses, department leaders were so impressed that they put her in charge of two graduate-level courses: Introduction to Human Services Practice and Advanced Human Services Practice.

The best example of Kramer’s style comes from her reaction to an interpersonal conflict between two students Winter Quarter. The class was extremely upset over the dispute. “I could have lost the class for the rest of the quarter,” admits the 31-year-old doctoral student. Instead, she delivered a lecture on the values of respecting diversity and the use of effective communication. She won the class over, notes one social work professor, who adds, “It was a piece of unforgettable learning for a group of fortunate students.”

Somehow Kramer has balanced her teaching duties with the demands of graduate study, including preparing for her doctoral exams given this spring. She hopes to have her dissertation—and degree—by June of 1992.

J.T. Ptacek

One of the aspects of teaching J.T. Ptacek likes best is the instant feedback it provides.

One of the aspects of teaching J.T. Ptacek likes best is the instant feedback it provides.

“You get your rewards every day with teaching,” observes the psychology teaching assistant and recipient of a 1991 Excellence in Teaching award. With research, he notes, results are usually two or three years away.

The 28-year-old Ptacek, whose given names are John Thomas, sees enthusiasm as a key to good teaching. Not just enthusiasm for the material but for the process as well. Some people are excited about the material, their own research or psychology in general, but find stimulation only discussing it with colleagues, he observes.

But not Ptacek. “I get in the classroom and I’m darn glad I’m there,” he says. “It’s a real emotional charge that sticks around for a couple of hours.”

Ptacek was born in Iowa and raised in Oregon. A 1985 graduate of Willamette University, he “floundered” for a year or two before entering the UW where he earned a master’s degree in psychology in 1989. Now writing his dissertation, he expects to get his Ph.D. in 1992.

One of his greatest challenges is serving as teaching assistant for a graduate-level statistics course. The material is demanding and the students, some of whom have math backgrounds superior to his own, are also his colleagues. “There’s the sense that I really, really have to prepare for this,” he says.

That preparation must be enough because, as one veteran of the class wrote in support of the nomination,

“J.T. was always available, patient and somehow able to translate the (to me) most abstruse statistical mumbo-jumbo into the kind of prosaic terms I could grasp.”

H. Mason Keeler

Next time you drop a hook in the water, while you’re waiting for that big one to strike, take a moment and thank H. Mason Keeler for what he once called his “investment in the outdoors.”

Next time you drop a hook in the water, while you’re waiting for that big one to strike, take a moment and thank H. Mason Keeler for what he once called his “investment in the outdoors.”

An avid sports fisherman for six decades, Keeler has given more than $2 million to the UW, most going to the School of Fisheries for research and education in sports fisheries, especially salmon and trout.

Keeler also encourages others to give to the University, especially to fisheries, as a volunteer for the current $250-million Campaign for Washington. Unique among campaign volunteers, he serves on three campaign committees—regional gifts, major gifts and leadership gifts—as well as the committee raising funds for his class’s 50th year reunion.

For his outstanding support of the University, Keeler receives the UW Alumni Association Recognition Award for 1991.

“I owe somebody something for all the pleasure I’ve had from the outdoors,” says the 1941 graduate in economics and retired president of Overall Laundry Services. “I want to make sure there are fish for tomorrow.”

Keeler has established the H. Mason Keeler Endowment for Excellence, the H. M. Keeler Lake Washington Fund for Fisheries (which supports the Seward Park Hatchery) and the H. Mason Keeler Professorship in Sports Fisheries Management. The professorship, currently held by Ray Hilborn, was matched with $250,000 in state funds through the Distinguished Professorship Trust Fund created by the state legislature in 1985.

Keeler’s gifts have made sports fisheries an important element in the UW’s overall research program, says Hilborn, and that’s something that few universities can boast. “The jealousy I get from friends on other campuses is impressive,” he adds.

“Mason Keeler has provided an enduring legacy not only to the University but to the Pacific Northwest,” says UW Foundation President Marilyn Dunn. “He is an enthusiastic advocate for and an extraordinarily generous supporter of the University. We are delighted to recognize his service.”

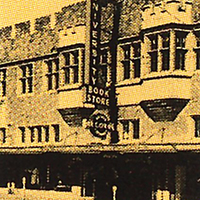

University Book Store

It’s the place you bought your textbooks and sold them back at the end of the quarter. It’s the place you went to buy a Husky T-shirt for your kid brother, a last-minute card for your mother’s birthday and, when the last exam was over, it’s the place you went to pick up your cap and gown.

It’s the place you bought your textbooks and sold them back at the end of the quarter. It’s the place you went to buy a Husky T-shirt for your kid brother, a last-minute card for your mother’s birthday and, when the last exam was over, it’s the place you went to pick up your cap and gown.

The University Book Store, which first opened for business on Jan. 10, 1900, in a cloak room in Denny Hall, has been named winner of the 1991 UW Alumni Association Distinguished Service Award.

“The University Book Store supports our membership program by making members eligible for its patronage refund program,” notes UWAA Executive Director Jon Rider. “In recent years it’s helped sponsor Alumni Association programs—such as Dawg Dash—that we probably couldn’t have carried out without their support.”

“My greatest ambition is to have people feel good about the book store,” says General Manager Bob Cross. “So when something like this alumni association (award) comes along it’s particularly meaningful.”

Achieving good will is not as easy as it may sound. “Students on any campus tend to look at the book store as the enemy,” Cross observes. “They are required to buy books they don’t want to buy and pay more for them than they want to pay.”

The University Book Store sells more books than any other college or university book store in the United States. In sales of all merchandise, it ranks third behind Harvard and UCIA. It stocks about 110,000 titles (out of about 800,000 books in print in English). “We probably have as large a selection of current book titles as any bookstore in the country,” he says. The textbook department carries more than 5,000 different titles any given quarter.

Cross credits the store’s success, in large measure, to its long standing and rather unusual status as a “for-profit” business independent of the institution whose students it serves. “The vast majority of college book stores are owned and operated by the college, located on campus … like food service or housing,” he remarks.

After occupying several locations on campus—including space in the old chemistry shack behind Denny Hall and the basement of the old Meany Hall—it moved, in 1925, to its present location on the “Ave.” where, through a number of property acquisitions and renovations, it has grown into the present 90,000-square-foot complex.