To some at UW, violence epidemic is a public-health issue

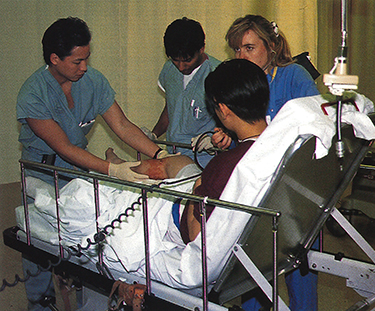

Harborview Emergency Room Doctor Rex Manayan (left) examines the gunshot wound in the leg of a 16-year-old shooting victim. Last year 241 patients were treated for gunshot wounds at Harborview. Photo by Larry Zalin.

“We exist at the bottom of the health care food chain …”

The language is concise and acerbic. It always is when Dr. Michael Copass speaks publicly about the rising tide of violence in America. As director of Harborview’s Emergency Trauma Center and a UW professor of neurology, Copass commands attention: For more than 20 years he’s watched the breakdown of U.S. society reflected in the halls of the emergency room.

The numbers bear out his stark point of view. Last year 241 patients were treated for gunshot wounds at Harborview, an increase of 29 percent over 1990. It cost an average of $17,047 to treat each shooting victim brought to Harborview in 1993. In 1972, Copass recalls, hospital staff treated an average of one gunshot wound a month.

“Was it only one shot?”

It’s a sunny early spring afternoon, and a Shepard ambulance crew has just wheeled a shooting victim into the Harborview Emergency Room.

Lying on a stretcher, the young man nods stoically to the doctor—he was only shot one time. Dr. Rex Manayan, a general surgery resident, verifies that the exit wound in the 16-year-old’s right leg is larger than the entrance wound.

“Can you feel that right there? Does that feel normal? How about there? Hold this toe up—that’s good.”

Manayan is testing for neurological, vascular and motor function. He presses his finger and pushes a pin in the vicinity of the wound to check the boy’s responses, and Manayan asks the youth to move his foot. After checking blood pressure in the area of the wound, Manayan decides no vascular damage has occurred. The physician tells the teenager that he will be X-rayed to check for bone injury.

“What kind of gun, do you know?” The young shooting victim says he thinks he was struck by a .22- or 25-caliber bullet. It’s not the heavy artillery that many gang members carry these days, but the teen-ager claims that gangs had nothing to do with his shooting.

The X-rays reveal no bone injury and that the bullet has exited the boy’s leg. After giving the teen-ager a xylocaine injection for pain relief, Manayan removes dead tissue and irrigates the wound.

Because his injury is minor, the youth will be able to go home with his father and sister. As he dresses the wound, Manayan tells the teen-ager how to care for his leg at home. ER staff schedule him for a follow-up appointment in the surgery clinic, and the boy is told to come back to the emergency room if there’s any sign of infection.

A police officer asks the 16-year-old to fill out a report, and she takes a Polaroid snapshot before she leaves. Despite the boy’s protestations, the officer has reason to believe that the shot was fired during a gang confrontation. Manayan gives the boy antibiotic pills and ointments. Leaning on his father’s shoulder for support, the teen-ager hobbles out the door.

On this day, March 25th, 1994, Harborview records its 81st gunshot injury of the year. Before December 31st, there may be up to 250 more.

Why is there so much violence now, and what can be done to stop it?

In the roaring political debate about how to curtail rampant violence, Harborview is in the line of fire. The hospital is Washington’s only Level One Trauma Center. As they treat trauma patients, physicians, nurses, social workers and psychologists face the effects of violence every day. Since they work at one of two UW teaching hospitals, the staff also conducts research on the causes—and prevention—of violence.

Harborview’s trauma registry—a system tracking every seriously injured patient admitted to the hospital—is a valuable tool for the public health aspects of violence. Of the people hurt by gunfire in 1993, 29 percent were younger than 20 years old. Victims aged 6 to 19 showed the greatest increase of any age group over the previous year. That information disturbs Dr. Abe Bergman, chief of pediatrics at Harborview.

“We’re still a cowboy society,” Bergman claims.

“Our nation hasn’t made the decision the Scandinavian countries have: ‘Thou shalt not drive when drunk. Thou shalt not carry a gun and shoot another person.’ These countries have as much of a democratic tradition as the U.S. has, yet they don’t accept this kind of violence.”

Bergman is one of the founders of the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center (HIPRC). Since 1985, the center’s researchers have looked at the problems of traumatic injury with an eye toward public health techniques. If cholera and smallpox can be controlled through research and prevention, the staff ask, why can’t the same effort can be made to limit the impact of trauma?

Holly Neckerman, a psychologist and research coordinator at the center, believes it may be possible to stop violence through prevention efforts. Asked to list the root causes of interpersonal violence, Neckerman runs off a litany of biological, social and economic factors: hormones, dysfunctional family patterns, access to weapons, peer support for anti-social behavior, gangs, poverty, racism.

“There are so many possible causes that it’s impossible to come up with one intervention,” Neckerman explains. “We need to start with young children and support positive behaviors. Any comprehensive approach, though, should include gun control—it’s part of the problem, so it’s part of the solution.”

Center staff are hopeful about violence prevention because they’ve seen public health tactics work on other injury problems. Harborview’s successful bicycle-helmet campaign shows that injuries can be prevented when behaviors change, according to Dr. David Grossman, a UW professor of pediatrics and acting director of the HIPRC. Thanks to the campaign, Seattle children’s use of bicycle helmets jumped from one percent to 60 percent in seven years.

Injuries aren’t accidents—they’re preventable. That’s the HIPRC credo, and Grossman explains that there are “windows of opportunity” when positive actions can minimize violent injuries before and after they happen.

No one is saying curbing violence is going to be as easy as the bike helmet campaign, but there are steps that can be taken. Interventions beginning in early childhood can prevent violent behavior later, Grossman points out. Reduced access to guns can lessen the severity of an injury during an act of violence. Once the violence has happened, programs of pre-hospital care, such as Airlift Northwest and Seattle’s Medic One program, can soften the blow. Access to regional trauma care and rehabilitation programs accelerate the healing process.

While no single point of view characterizes the opinions of all the UW faculty based at Harborview, most feel that patient care after violent events is stronger than efforts to stop shootings, stabbings or abuse from happening in the first place. Thanks to Copass’ leadership in developing trauma care, victims of violence are assured rapid and extensive treatment for their injuries. The number of deaths from gunshot wounds would be even higher if there weren’t this high-tech medical care.

“There’s now good tertiary care for victims, but prevention efforts are lacking,” explains Social Work Professor Karil Klingbeil, director of social work at Harborview. A frequent expert witness in legal cases involving acts of violence committed by battered spouses and children, Klingbeil has strong views on what can be done to stop the cycle of violence.

From left, Harborview’s Karil Kingbeil, Dr. Michael Copass and Roland Maiuro.

“The current public health model, in vogue since 1959, has led to a passive attitude toward violence,” Klingbeil says. “The model talks about the issues—from prevention to trauma care—but it doesn’t assign responsibility for doing anything about the problem.” She espouses what she calls an “action-responsibility” model emphasizing individual and community action. No one, she argues, is off the hook.

“The individual has an obligation to report violent acts or any other form of interpersonal violence, including name-calling,” Klingbeil says. “Take action when you know something is wrong: tell another person, report it to the police, provide support. We should be as comfortable helping victims of violence as we are helping someone who’s sick with cancer. The least we can do is say, ‘You don’t have to live like this. There are people who can help you.’ ”

Violence-recognition training should be required for health care professionals, Klingbeil says, just as mandatory AIDS training is now. Reforming child-rearing practices to emphasize caring and nurturing, affordable child care, banning guns, and reducing violence in sports and in the media are all aspects of her action-responsibility model.

The political dimension is another key to preventing violence. Klingbeil urges concerned individuals to join citizen groups, teach adult literacy, and get involved in court-sponsored programs that divert first time juvenile offenders from jail into positive programs. Vote on the basis of how candidates stand on interpersonal violence.

“The last legislative session did little to remedy the problem, apart from passing the Pasado Bill to increase the penalty for cruelty to animals,” Klingbeil says.

Like Klingbeil, Roland Maiuro is a forceful advocate for new public health approaches to violence. A UW psychology professor and director of Harborview’s Anger Management and Domestic Violence Program, Maiuro wants to identify high-risk populations and find ways to prevent individuals from becoming perpetrators and victims of violence.

There are key factors that make some children prone to violent behaviors, Maiuro explains. Learning disabilities and hyperactivity are often linked with impulsive, aggressive acts. Drawn to daring behaviors that go right to the point of being injurious to themselves and others, these youthful “action junkies” frequently grow up to be adults who commit violent acts. Bullies who learn to get what they want through intimidation need immediate corrective feedback, Maiuro says, before the behavior is reinforced.

“Children’s direct exposure to domestic violence—either by observing parents beating each other or by suffering as victims—is the single most powerful risk factor for generating violent individuals in our culture,” Maiuro explains. “If these kids don’t go on to have dysfunctional families of their own, they often become general offenders. The prisons are filled with people having these histories.”

Gang activity and the availability of guns are two other crucial elements in the rapid growth of violence as a means of resolving conflict, Maiuro maintains. What would have been a rumble in past years, he says, is now a homicide.

“There seems to be an inappropriate tolerance for gang activity, as if it’s somehow an acceptable form of cultural diversity,” Maiuro says. “Gangs are an updated version of underworld activity tailored to specific cultures and a younger age group. They entrap individuals into believing they don’t need to operate under the same rules other people do. Gangs compound poverty by creating a false landscape to operate in.”

An array of guns were turned in to the Seattle police during a 1992 buy-back program. Harborview expert Holly Neckerman says any comprehensive approach to violence should include gun control. “It’s part of the problem, so it’s part of the solution.” Photo by Benjamin Benschneider, © 1992 Seattle Times.

Maiuro advocates what he calls “pro-social solutions” that provide children alternatives to violence. Late-night programs in community centers offer a positive environment that children appreciate, Maiuro says, and lessons can be taught through activities that they enjoy. Traditional classroom approaches tend to help children who need the help least, he explains, and too many kids are failing.

“Let’s find ways for students to distinguish themselves in ways other than classroom success,” he says. “Schools are places for learning all sorts of lessons in life. Why not include teachers who are in business or vocational trades and may not be college grads. Let plumbers teach in public schools, not just in trade schools for people who realize their 12 years of education haven’t gotten them anywhere.”

Maiuro cites an item he saw on the local news that illustrates positive alternatives for children. “A group of kids were at the Seattle Center for the unveiling of a wall mural they’d made at school,” he recalls. “One of the little girls was interviewed and said, ‘I’m so excited, I could jump up and down and scream.’ It was a wonderful example of how kids can get high on that kind of recognition.”

Punishment has its place, Maiuro says, but it’s being overused. He cites the “three strikes, you’re out” initiative passed last fall by Washington voters as an emotionally satisfying approach that does little to stop the cycle of violence. If our interventions aren’t as sophisticated as the problem, they’re bound to fail.

“The correctional system is our new military-industrial complex, designed to combat our current and most formidable enemy, the one within,” Maiuro argues. “The approach has all the negatives that the military-industrial complex had in remedying issues of democracy and freedom. If the problems are poverty and the lack of a vision of what people can do for themselves, we can’t just be bombing them or locking them in prison. It amazes me how that lesson hasn’t been learned.”

Many citizens now feel that the criminal justice system can take care of the problem, Maiuro says, with the police as our “army” and prison inmates our “POWs.” If current trends continue, Maiuro projects that by the year 2050 everyone in the U.S. will be either a member of that police army or behind bars.

“We need to decide if this is an image of the future we’re comfortable with.”