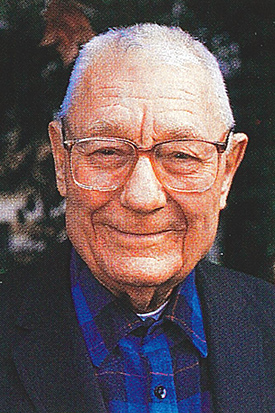

To Spain, Bob Reed, ’65, ’67, is a war hero

Bob Reed, ’65, ’67, says he is not a hero, but don’t tell the Spanish government he said so. Two years ago, Spain offered Reed an honorary citizenship for fighting in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Reed, who was 22 when he volunteered to fight in 1937, is now 84 and is the last living UW alumnus who is a veteran of the conflict, the “dress rehearsal” for World War II.

Bob Reed, ’65, ’67, says he is not a hero, but don’t tell the Spanish government he said so. Two years ago, Spain offered Reed an honorary citizenship for fighting in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War. Reed, who was 22 when he volunteered to fight in 1937, is now 84 and is the last living UW alumnus who is a veteran of the conflict, the “dress rehearsal” for World War II.

While the Spanish Civil War may be a historical footnote to younger alumni, it was a rallying point for leftist students and workers in the 1930s. With the backing of Hitler and Mussolini, Generalissimo Francisco Franco led a military coup to overthrow the Spanish Republic, which had the support of socialist, communist and other leftist groups.

At the time of the coup in 1936, Reed was a labor organizer in Arkansas and Michigan. A number of his friends in Detroit volunteered to fight in the International Brigade of the Republican army. “I debated about going. It was a matter of conscience,” he recalls. “If fascism isn’t stopped there, where will it be stopped? We had to give it our best shot. And we thought we’d win.” Nearly 3,000 Americans fought in the International Brigade, which had a total of about 40,000 volunteers; by the war’s end about half of the Americans would be dead.

Reed found out how hard the war would be before he even stepped on Spanish soil. An Italian submarine sunk the City of Barcelona, the ferry he and other volunteers were taking from Marseilles to Barcelona. He saw plenty of action during the conflict, including the winter battle of Teruel and the retreat and recrossing of the Ebro River. While taking a fortified hilltop in one battle, a bullet penetrated his helmet. “It was a minor head wound, but if it had been an eighth of an inch lower, I wouldn’t be here today,” he says.

While Germany and Italy poured men and materiel into Franco’s army, Britain, France and the U.S. had a policy of non-intervention. Only the Soviet Union supported the Republic. “We were overwhelmed by airplanes and machine guns,” Reed says. “We just didn’t have the stuff to fight with.” Reed admits that he suffered from mood swings.

“We can’t possibly do this,” he remembers thinking, “but we were hoping the blockade would be lifted. It never happened.”

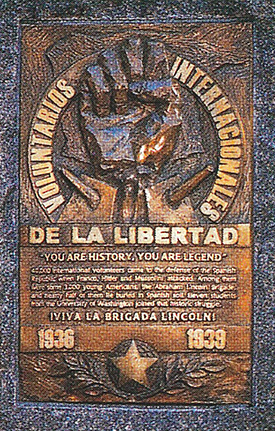

The first U.S. monument to volunteers in the Spanish Civil War.

The International Brigade was disbanded in late 1938 and Reed made his way back to Detroit. The Republic collapsed in early 1939. After Pearl Harbor he immediately signed up in the U.S. Army. “I was happy that fascism was finally going to be defeated and I hoped that Franco would be put out of power too,” he says. After serving honorably in the second world war, he tried his hand at writing the Great American Novel and worked for a left-wing newspaper. But during the post-war crusade against Communism, the brigade’s politics put its members in jeopardy. In 1947, U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark released a list of “subversive” organizations that included the brigade and its veterans.

Reed says he had to “lay low” during the height of the Red Scare. He found out the FBI was questioning his former neighbors and believes he was fired from one job for his political beliefs. However, he questioned his own activism as well. “Politically things were in chaos on the left. Gradually my activism just faded away,” he says.

When his wife completed her social work degree and found a job in Seattle, the couple moved to Washington. Reed decided to make a fresh start. “I grew up on a farm in Texas. We were dirt poor. I couldn’t go to college when I graduated from high school.” So, in 1961 at the age of 47, he enrolled at the UW. He earned a B.A. in anthropology in 1965 and, working with Professor Larry Northwood, a master’s in social work in 1967. After school he spent most of his career as the director of the Holly Park Neighborhood Center in south Seattle.

But he never forgot his fellow veterans and tried to keep in contact. His personal papers on the brigade are deposited in the UW Libraries. And on Oct. 14, he was part of the dedication of the first monument in the U.S. to American volunteers of the conflict: a block of granite with a sculpted bronze plaque located just west of the HUB on the UW campus. The monument, which was privately funded, was spearheaded by Abe Osheroff, another veteran who resides in Seattle.

For Reed, perhaps the most moving monument came in November 1996, when all the living members of the International Brigade were invited back to Spain and honored at a special ceremony in Barcelona. “It was almost unbelievable. It was just a tremendous experience,” he says. When the government offered all veterans honorary citizenship, Reed says he was extremely touched. “I never expected that to happen. I’m gratified but I don’t consider myself any kind of hero. What I did was normal for me.”