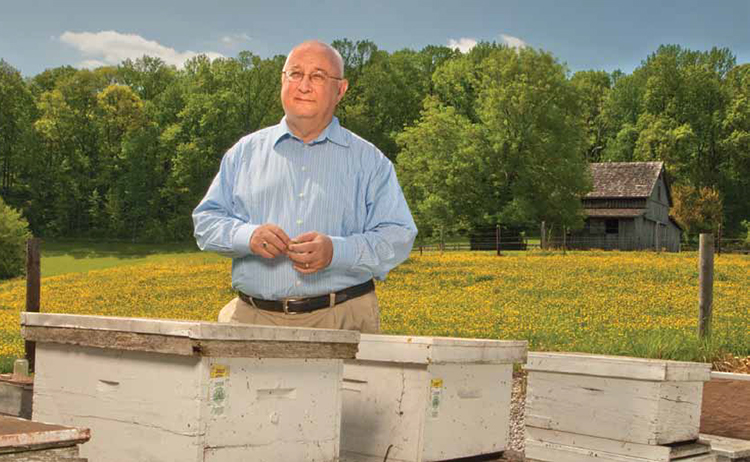

Triple alumnus Charles Wick got to the bottom of honeybee ‘plague’

Charles Wick, ’71, ’73, ’79, may not wear the trademark deerstalker hat and smoke a long-stemmed pipe but when it comes to bees, he’s an ace detective. In fact, his acumen helped provide the answer to one of the most troubling mysteries in today’s natural world: What is killing the honeybees?

Officially called “colony collapse disorder,” the bee “plague” is so serious it has been threatening U.S. food production. Some experts suggest that because bees are essential pollinators for many different kinds of plants, up to one-third of America’s yearly food crop could be wiped out eventually if the epidemic spreads throughout U.S. agriculture.

While insects have not been his field of study, Wick brought to the problem a 28-year career as a nuclear, chemical and biological weapons expert with plenty of molecular detective experience. Wick retired from the Army in 1999 as a Lieutenant Colonel with 25 decorations and citations for his cutting-edge research. Currently a microbiologist with the Army’s Edgewood Chemical Biological Center northeast of Baltimore, Wick holds the patent for the Integrated Virus Detector System (IVDS) that allows the military to test for and identify biological threats.

In the case of the bees, Wick used mass spectroscopy imaging—measuring a compound based on its mass and recreating it as an image—to track peptide sequences in the bee protein. By pinpointing the structure of the peptide DNA, he and his team were able to identify a “foreign” protein from viruses and fungi that had attacked the dead bees.

After two years of investigation, Wick’s team discovered that every dead bee was carrying a unique peptide belonging to a bee-attacking “iridescent virus,” as well as a protein from a fungus (nosema ceranae) known to be lethal to bees.

Wick and his team worked with researchers at the University of Montana in Missoula and at Montana State University in Bozeman to discover that a virus/fungus combination was giving the bees a killer double-whammy. It appears the combination of the two did the deadly damage as neither the virus nor the fungus can kill bees independently.

How did Wick and his team of Army researchers end up working with academic researchers in Montana? Nothing less than serendipity. Wick’s brother, David—who studied botany and microbiology at the UW from 1971 to 1976—understands how his brother’s rapid virus screening instrument worked. David, a Montana entrepreneur, happened to catch a television interview with a Montana researcher who talked about bees. He also happened to have met the researcher and retained his business card. The two research teams with their disparate perspectives came together because David Wick imagined the possibilities.

Although the army/academic liaison did not produce a cure for the problem, figuring out the cause produced concrete advice for beekeepers. Because both pathogens—the virus and the fungus—flourish in cool, wet conditions, Wick counseled beekeepers to keep the bees as warm and dry as possible.

Ask Charles Wick how he and his germ analysts figured out the puzzle and he’ll tell you it was “mostly a mostly a matter of looking at what was right there in front of your nose.”

Wick credits his ability to really “see” as a scientist to an experience he had as a UW undergraduate walking around campus with Forestry Professor Reinhard Stettler, now a UW professor emeritus. Wick asked Stettler what he should study to become a scientist. Stettler pointed to a pine tree and said, “Why don’t you study that? See what you can learn about it on your own, then get back to me.”

“What Professor Stettler taught me that day was how to look closely at things,” Wick says. “That’s the first step on the road to discoveries.”