Universities and sports have always been a turbulent marriage

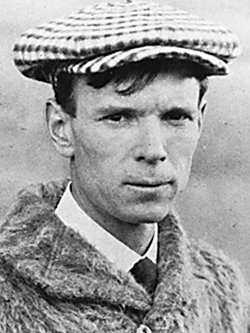

UW football coach Gilmour Dobie.

The alumni were angry. They had had enough of the rampant commercialism of intercollegiate athletics—especially the salary of the football coach. It is time to shrink back on the excessive competition, they declared. Some even suggested playing against teams only from Washington, Idaho and Oregon.

But why should I summarize the controversy when I have the account in writing at my desk:

“A resolution will be offered at the annual [alumni] meeting asking the association to go on record as opposed to intercollegiate contests with institutions outside of the states of Washington, Idaho and Oregon. … The resolution is good as far as it goes. But why not strike at the root of the matter-why not resolve against the commercialism which is rampant in not only the undergraduate’s athletics, but which is spreading into every line of these activities as well?

“Everything is measured today in gate receipts. There is scarcely a function during the college year, in which the question, ‘How much can we make?’ does not enter. … Few activities are carried on for pure love of doing. It is come to such a pass that the student who is willing to do something for nothing is regarded with suspicion. … This state of affairs is a result of the athletic policy of the American university today. The football coach is paid more money for three months’ work than a dean gets for the year.”

These words come from the May 1910 edition of the Washington Alumnus, the original title for Columns, during the coaching tenure of Gilmour Dobie, whose nine seasons as a Husky football coach set an NCAA record with 58 wins, three ties and no losses.

UW President Henry Suzzallo.

The resolution never passed and Dobie had six more seasons before he was fired by a new UW president—Henry Suzzallo. During the 1916 season, one of the star football players had examination “irregularities.” The faculty investigating the incident recommended suspending the player before the final game of the season against California. The players went on strike, insisting the suspension come after the game. Dobie backed the players while the new UW president backed the faculty.

The Sundodgers (as they were called then) finally ended their strike and beat Cal 14-7 without their star tackle. But eight days later, Suzzallo issued the following statement: “Mr. Dobie will not be with us next year. That is now final. The chief function of this University is to train character. Mr. Dobie failed to perform his full share of this service on the football field. Therefore, we do not wish him to return next year.”

While Dobie made his mark on Husky football, there is no question who made his mark on the history of the University of Washington. Suzzallo came to a quiet college in a far corner of the nation. When he left in 1926 (ironically, he was also fired), it was on its way to becoming one of the premier public universities on the West Coast—and eventually the nation.