UW alum recounts 13 days in the hands of Colombian guerrillas

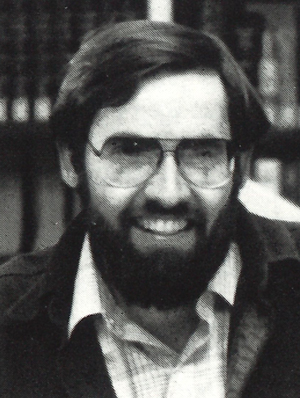

David Kent

It was 7 a.m. on Feb. 13 when David Kent stepped out of his house in Medellin, Colombia, and into his 1982 Suzuki, heading for his job as a school librarian. Suddenly a man, claiming to be an anti-narcotics policeman, appeared at the car’s window and flashed a badge.

Kent, a 1979 UW graduate, asked for more identification. The man pulled out a gun. “I guess that’s enough ID,” Kent told his abductor, displaying a sense of calm and even good humor that characterizes his description of 13 terrifying days spent in captivity at the hands of an ultra-left-wing guerrilla group, the National liberation Army. The group, which is not linked to the drug cartel, is one of Columbia’s most dangerous revolutionary cadres.

Forced into the back of his own car, the captors took Kent to what he calls a “guerrilla house” somewhere in Medellin. Kent says he was physically well-treated. In fact, a toothbrush, deodorant and slippers awaited him at his arrival. He was also assured that his abduction was nothing personal, merely a symbolic gesture to protest President George Bush’s visit to Columbia.

His captors, always armed, also promised they would hold him only two or three days. But Kent’s symbolic captivity took an ugly turn after he criticized the guerrillas’ Marxist philosophy. The kidnappers quickly branded him an enemy of the revolution and reminded him that his words could serve as evidence in a revolutionary trial. “And I know the outcome of a revolutionary trial,” Kent says. “Maybe it was foolish. I did end up making them angry.”

After four days, under cover of darkness, he was moved to a remote mountain location. “I didn’t know if they were taking me to the country to put a bullet through my head,” says Kent, who practices meditation. “I tried to prepare myself for the adventure of dying.”

During Kent’s mountain captivity he was visited by “head-honcho-type” guerrillas who said the organization would contact him after his release. Finally, on Feb. 26, he was handed over to a local commission. During the ordeal Kent had developed hepatitis. He went to the hospital, took a vacation, and then prepared to leave Columbia well in advance of the guerrillas’ threatened return. “I’ve been getting ghost telephone calls,” he says. “I don’t want to live like that.”

A graduate of the UW’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science, Kent began his life in Columbia six years ago, just about the time the drug cartel was going into high gear. “The last six years have been violent years for Columbia,” he observes. “It’s been an interesting time to be here.” Kent returned the U.S. April 21.