UW alumnus takes readers inside the Balkans’ postwar struggle

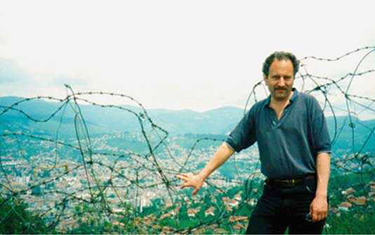

Peter Lippman

Peter Lippman has always followed his own True North—his most deeply held values as a human rights activist. While many of us look away in times of human tragedy, Lippman faces the suffering of others with compassion. He listens, he observes, he writes. And he acts.

Much of his work has involved the Balkans. He has strong personal connections to families in Bosnia, where he bore witness to the aftermath of the bitter war that raged from 1992 to 1995, claiming more than 100,000 lives. (The war involved Bosnian Serbs, Croats and Bosniak Muslims.) This was after an interest sparked during his teenage years, when he helped found the Radost Folklore Ensemble in Seattle and traveled to the Balkans on tour in 1981. While in northern Serbia, he studied Serbo-Croatian and the local folk music scene.

Vanderbilt University Press just published Lippman’s new book, “Surviving the Peace: The Struggle for Postwar Recovery in Bosnia-Herzegovina.” It’s a book no one else could have written, given Lippman’s decades of grassroots connections to the people there.

Lippman on a visit to the region in 1999.

Lippman, ’95, and his three brothers all became human rights activists because socially progressive involvement and awareness of other cultures was the mother’s milk of politics in the family home. “From the age of 10, I wanted to learn languages and travel,” he says. “My whole family was politically aware and progressively oriented, anti-Vietnam War, anti-nuclear.”

In late 1992, Lippman read a newspaper article that said refugees from Bosnia were coming to Seattle. “I called a lot of my friends and we set up a grassroots organization to help a family,” recalls Lippman. He quickly became close to the family because he could speak their language. “Which explains why I went back to Bosnia after the war. I became curious about how they became displaced and their village bombed, and their relatives killed and put in concentration camps,” he explains. “I became curious about what would happen after the war.”

As a student in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, he expanded the context for his human rights work. “Before, I didn’t even know what an NGO was (a nonprofit organization that operates independently from government.) My UW education helped with my reading and writing, and I familiarized myself with new aspects of international politics,” says Lippman.

In 1995, he returned to Bosnia for two years and since then, he has been back 17 more times. As a self-employed building contractor, Lippman has the flexibility to travel frequently to the region.

Lippman’s book comes after more than two decades of study.

The story of Bosnia 25 years after the war is not an uplifting tale. Lippman says the unemployment rate approaches 40 percent and that there has been a huge exodus of people. The country’s population has dropped from 4 1/2 million before the war to under 3 million today. Bosnia’s two biggest problems are corruption and the lack of work opportunities. In his view, hope hinges on the grassroots activists because he says the international community stopped caring once the guns fell silent.

“The leaders have goons who try to intimidate grassroots activists who are fighting corruption and working for better living conditions and the right of return for war refugees,” Lippman explains.

When he’s home in West Seattle, Lippman plays Balkan folk music as well as Klezmer music in a band called Malke and the Boychiks.

Lippman, who is 67, doesn’t intend to give up his day job just yet. “When I can’t carry a 60-pound bag of concrete up a ladder, then I’ll stop,” he says. But he’ll continue giving voice to the people the international community has largely forgotten once the killing stopped.

To read more of Lippman’s writing over the past 20 years, go to http://balkanwitness.glypx.com/journal.htm.