UW experts weigh in on the crisis in the Gulf

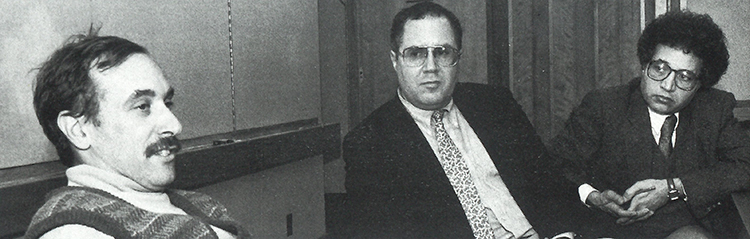

UW Middle East experts (from left) Ellis Goldberg, Jere Bacharach and Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak.

UW Professors Jere Bacharach, Ellis Goldberg and Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak met with Columns Editor Tom Griffin in mid-October to discuss developments in the Persian Gulf. Bacharach is chair of the UW Department of History and heads the Middle East Studies program in the Jackson School of International Studies. Goldberg is a political science professor and specialist on the Middle East. Karimi-Hakkak is a professor in Near Eastern languages and civilization and an expert on Iran. Excerpts from their discussion follow.

GRIFFIN: One commentator said that the West is basically refighting World War II, the destruction of defenseless nations by a cruel and powerful dictator, whereas the Arab world seems to be fighting the Crusades, Western nations seeking to occupy and colonize their countries. Is this an accurate assessment?

GOLDBERG: It’s not clear to me that either of those descriptions is very apt. George Bush probably thinks that he’s refighting World War II in some sense, and I suppose that a lot of people have decided this is Munich 1938. The thing that I find most remarkable about that is the assertion that Iraq, with 17 million people in the world of 1990, is somehow to be equated with the Germany of 1938. I just find that a stupid, blind kind of assumption and one that’s remarkably wrong-headed, regardless of anything else that you think about the Gulf. There are a lot of other issues here, most of which have to do with the exhaustion of the Iraqi regime due to the war with Iran.

BACHARACH: Let me pick up from what Ellis was saying in terms of perceptions …. While I believe that the public statements of the administration speak of the defense of a nation which has been overrun by a foreign invader, the primary reason that the U.S. is in that area … is to ensure the relative free flow, at a relative stable price, of an absolutely essential element in the world economic system—oil. The great fear on the part of the administration and many Europeans and some others is that Saddam Hussein’s conquest will put him in a position to dictate world oil prices and their supply.

GOLDBERG: I think based on recent history, the fear of lots of people is that the U.S. will get what it wants at the expense of everybody else who lives in the Middle East. If oil prices are low relative to what the market will bear, then that represents a transfer from one person to another. It’s a subsidization of the U.S. and the West.

… I don’t think either analogy is very helpful in understanding what’s happening. I don’t think the average American believes we are refighting World War II. I don’t think the average Arab thinks that they’re refighting the Crusades. What [Arab] people see themselves as fighting once again is the anti-colonial struggles of two decades ago …. The sense here is that the West is prepared now to inflict enormous punishment on Iraq largely because the West would prefer to do that, than face a powerful oligopolist in the oil markets.

GRIFFIN: I’d like to talk about the present situation, perhaps the strange alliance we see right now with Syria aligned with the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, Egypt and the Gulf nations. How long can a structure like this hold up?

BACHARACH: I would say that leaders in nations try to act in what they perceive, or define, as the national interest. The U.S. is involved in what it perceives is its national interest. Syria, whose priorities often are at odds with those of the United States, but not always, acted in this particular crisis in what it sees as its national interest. … The alliance will last as long as each individual participant sees that there is still some advantage for their priorities to be a member. If the Palestinian-Israeli issue comes to dominate and the U.S. is being perceived as having unlimited support for the state of Israel, then the obvious cracks in the alliance will emerge.

GRIFFIN: Secretary of State James Baker was floating around the idea of an alliance, a “NATO-on-the-Gulf’ pact. Do you think there’s much realism in that? KARIMI-HAKKAK: Alliances are difficult to form, especially in countries which have had long histories of difficulties with one another. I don’t see in what form it could succeed in establishing a Persian Gulf NATO kind of organization.

BACHARACH: Let me go further. I think that the pushing of such an alliance, or the statements that the United States intends to spend an indefinite time in the Arabian Peninsula, are some of the more damaging statements coming out of the administration. Up until this point, they have orchestrated their position extremely well in trying to get a united front against the Iraqi invasion. But one of the great sensitivities of the nations and the populaces of the Middle East region is the fear that the Americans will use this as a justification for a long-term, obvious, open presence.

GOLDBERG: Actually I think that to some degree people are afraid that the U.S. will use its power in the Middle East in precisely the wrong way …. Under Ronald Reagan we talked about democracy but did nothing. We now have decided to stop even talking about it. Which means that the idealist strain of American foreign policy has completely vanished and now we have this kind of cruel realpolitik, realism, neo-realism. We want their oil cheaply and they want to sell it to us expensively. Nobody is going to die for very long for that kind of deal.

… For the last decade and one-half, the U.S. has not frankly cared very much about the issues of democracy or the nature of the regimes …. I think given what’s going on in Kuwait, the dramatic refusal of the Kuwaitis for years to recognize the barest rights of non-residents, . . . the refusal of the Kuwaiti emirs to allow a parliament to exist except when it suited their very narrow purposes, the repression of the Shiah community in eastern Saudi Arabia by the Saudi ruling family, the repression of every attempt to form a trade union, the refusal of the Saudi royal family to allow democratic reforms to occur in Saudi Arabia, I think those should be at the top of the agenda.

Frankly, from my point of view, it’s time for the U.S. to tell the Saudis, we can’t defend a country like this. We learned this lesson in Vietnam and American boys can’t be sent to do what Saudi boys have to do for themselves. If you want a country that you can defend, you’ve got to change the country. If you don’t want to begin to change the country, frankly, we’re out of here. OK. We’ll buy oil from Saddam Hussein because we can afford to buy oil. You want us to defend you, you’ve got to have a country that you can defend. And frankly, since there are about eight million Saudis, they presumably should be a match for the 17 million Iraqis. Vietnam, with 80 million people, held off 1.1 billion Chinese in the 1970s.

KARIMI-HAKKAK: The question really goes to the heart of the dilemma. I think this whole notion of what kinds of regimes we form alliances with ought to be at the top of the agenda. You know, we speak a lot about the American way of life and we seemed to have developed a semantic equivalent for that—the low price of oil. But, the American way of life ought to at least include something more substantial, more valuable than that, more worthy of defending. If the American way of life includes the notion of democracy then the realistic politics Ellis is referring to is a travesty.

BACHARACH: I have some problems. In an idealistic way I agree with both Ahmad and Ellis …. I concur with both of my colleagues that one of the tragedies of American foreign policy throughout the world is our failure to demand greater democratic institutions in numerous parts of the world—this is not unique to the Middle East by any means. I am not sure ultimately how much leverage we really have.

GRIFFIN: Can we talk a little bit about the current stalemate here? President Bush has been very strong—not willing to negotiate at all—he just says to Saddam get out of Kuwait first. Do you think he’s drawing too hard of a line in the sand?

BACHARACH: My feeling is that we have a president and coterie of people around him whose goal is to eliminate Saddam Hussein and—I have nothing positive to say about Saddam Hussein—but I think that the goal of the American foreign policy at this moment is not the restoration of some governmental system to Kuwait. I think it is a larger goal and since it is a larger goal which includes the elimination of Saddam Hussein, I’m not sure what room there is for negotiation on the American side, and I could understand why Saddam Hussein would not perceive any room for negotiation on his side.

GOLDBERG: We’ve structured it as a zero-sum game. Our wins are their losses. Their wins are our losses and until you commit force nobody knows who’s actually telling the truth.

KARIMI-HAKKAK: And I think that’s the kind of line in the sand that’s likely to be blown away by the desert wind. I think, in other words, the time is playing very much in favor of Saddam and the actual establishment of his invasion of Kuwait and the development of events as if it could be a permanent change in the region.

GRIFFIN: You don’t feel the sanctions are going to have any effect?

KARIMI-HAKKAK: Show me one kind of embargo that has had the desired effect. I just don’t think embargoes work.

GRIFFIN: Do you both agree with that?

BACHARACH: I think there’s another element here. I’m not sure to what degree they will have an effect. I want to pick up what Ahmad was saying in a different way, and that is part of Saddam Hussein’s policy is what I will call, badly, the “Iraqization” of Kuwait. The Iraqi army demonstrated in the long and terrible war with Iran that on the defense, it was brilliant. … Taking that concept and applying it to Kuwait, what Saddam Hussein is doing is repopulating the country with as many Iraqis as possible, so that the troops who are there are not invaders but are going to be ending up defending their apartments.

GOLDBERG: Do we dare say it’s like the policy that Ariel Sharon would like to have take place on the West Bank?

GRIFFIN: Do you think there is a lot of pressure for a war in this respect, not only from Bush’s advisers but also from the other parties, the Saudis, the Israelis, the Egyptians?

GOLDBERG: The Saudis and Kuwaitis evidently want to.

BACHARACH: I would say those two …. The Israelis are going to lose no matter what happens. On one hand I think there are leaders within the Israeli political community who would like a war for two sets of reasons. The first is that it would immediately take the pressures off of them vis-a-vis the Palestinian issue. The second reason is that the invasion of Kuwait demonstrated that the role of Israel as a strategic ally, and the only stable base that the U.S. had in the Middle East, was, in this particular case, not valid. And since oil is a U.S. priority—back to pragmatic rather than idealistic goals—in order to demonstrate … the Israeli value to the U.S., a war where they can play an important role would enhance their position vis-a-vis the U.S.

GOLDBERG: I think the Israelis’ strategic thinking here is probably simply more precise than American strategic thinking. The Israelis have the same problem. When they fight a war, they can’t fight a very long war. Wars are very destructive and very unpopular in a certain way in Israel. They cause lots of internal dissension if they are prolonged.

GRIFFIN: Getting back to Professor Bacharach, you said Israel is going to be a loser no matter what.

BACHARACH: If there is a stalemate, then the linkage with the Palestinian issue becomes more and more prominent. The necessity of addressing the Palestinian issue to hold the alliance the U.S. has created together becomes more and more apparent as the degree to which they are a strategic ally lessens. If a war takes place and Saddam Hussein sees himself in serious trouble, what he will do is fire some missiles at the Israelis in the hope that he will get them to be militarily involved, to split the Arabs.

GRIFFIN: Will he succeed in that?

BACHARACH: Well, I would think that for both the Egyptians and the Syrians it would be an impossible dilemma. If the Israelis are attacking the Iraqis I don’t know on which side the Syrians would want to be. They don’t like either.

GRIFFIN: Many Palestinians are linking the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait with Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, the Golan Heights and Gaza. Basically, aren’t they the same thing, in the sense that a country has invaded another country and taken over the territory?

KARIMI-HAKKAK: Sure, it is the strongest argument you can make to the Arab masses these days. The analogy is very anchored in their minds and it has the power to mobilize them. That, in itself, is an important issue rather than whether the analogy is actually true or not. The analogy has the power to move, has the power to uncover what we call the hypocrisy of American foreign policy, the double standard so to speak.

BACHARACH: I think here, and I differ slightly, I would absolutely concur with Ahmad’s statement, that it is the appeal of the analogy …. I think that there are a lot of fundamental differences in the historical developments that took place in terms of the territorial occupations, but whatever I may believe and footnote has nothing to do with a perception which links these two as being analogous series of occupations. Since they have become so powerfully linked in the minds of (at least from what we can understand) the Middle East masses, and in the minds of at least a number of Middle East leaders, they for all intents and purposes have become linked.

GOLDBERG: … I don’t understand exactly what the problem is. Most states in the world today do seem to believe that the Israelis ought to end the occupation of the West Bank. Israelis themselves, up until very recently, were moving in that direction. A very eminent Israeli academic … suggested immediately after the invasion that Israel unilaterally return the West Bank to Palestinian sovereignty precisely to deprive the Iraqis of this issue. One can argue very obviously that there are similarities …. The other question is should they be linked at a [peace] conference? It seems pretty clear that Saddam Hussein wants them linked, because he knows that it’ll make it more difficult for anybody to get him out of Kuwait and the U.S. wants them not linked because they believe it’ll make it easier.

GRIFFIN: Could something good come out of all of this? Could this lead to a democratic solution for the Kuwaiti and Saudi Arabian populations? Could there be a settlement to the Israel-Palestinian question? Could you see a happy ending?

GOLDBERG: It depends on timing. Was there a happy ending to World War II and if so, was that the best way to get to that happy ending? These aren’t very useful questions in the end.

GRIFFIN: Is it a possibility?

BACHARACH: Let me respond differently. The first thing is that your question is what I call an American question. That is, somehow there has to be happy answers or solutions, that somehow things get wrapped up in a neat package and everyone goes home happy. I don’t think most events in most parts of the world work that way. … I think that whatever comes out of Northern Ireland would be an analogy for me. There is no solution to Northern Ireland in a nice, neat American way. There is no solution to the Arab-Israeli question. There are serious areas in which accommodation could be made, in which some very important compromises and changes could be undertaken, which could significantly improve the position of Palestinians and in many ways the position of Israelis …. The second thing is that we’ve spoken a fair amount criticizing the lack of democracy in Kuwait and I will have to agree with all of that, but I think that those terms should not be limited to Kuwait. I think that the region as a whole has been unfortunately noteworthy for both the lack of democratic institutions and the lack of serious discussions about democracy …. If in fact there is a movement toward greater democratic institutions throughout the whole region, whether they be in Kuwait, Iraq or any other nation in that region, then, in that sense, there has been a positive benefit of this whole tragedy.