UW grad overcomes near-fatal disorder to succeed in marathons and medicine

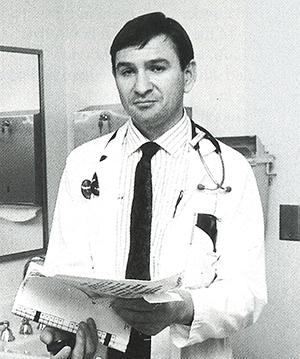

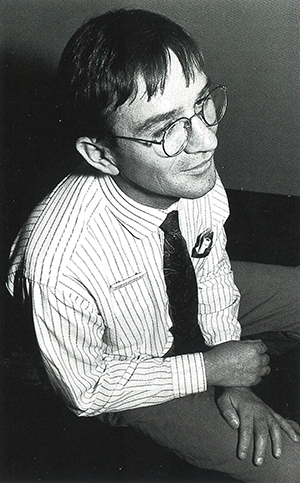

Dr. Jeffrey Dutton, ’86, ’91. Photo by Mary Levin.

Feeding Jeffrey Dutton costs about $125,000 a year, yet you would find that his grocery bills are ridiculously low.

Dutton, a 3:30 marathon runner and 1991 UW medical school graduate, obtains all his nutrition from fluid that is pumped into his body through a shunt—a slender, resealable tube implanted into a blood vessel near his heart. The technique is called home parenteral nutrition (HPN). Nicknamed the “artificial gut,” HPN has kept the 36-year-old Oregon native alive and vigorous since his body suddenly stopped absorbing food in 1976.

In fact, Dutton is exceptionally vigorous. He ran the New York City Marathon in 1985 under the sponsorship of the Achilles Track Club, a group of disabled athletes. Within the last year he raced in Poland and the Soviet Union. He planned to run in the 1991 New York Marathon until he developed an infection affecting the shunt. Dutton, now a resident in psychiatry at the UW, generally runs the 26 miles in about four hours. His best time is 3 hours 30 minutes.

The commitment to run a marathon is a “major decision,” says Dutton, because of the extra fluids demanded by the training process and the amount of time it takes to pump them into his system. Normally he spends nine out of every 24 hours hooked up to a pumping mechanism that forces a blend of amino acids, glucose, vitamins and minerals into his body. He usually hooks up the apparatus at about 9:30 in the evening and lets it run until 6:30 the following morning. Training for a marathon adds an extra seven to ten hours of pump time each week.

While the pump runs Dutton goes about his normal life—reading, studying, watching television, sleeping or, if he happens to be on night call, seeing patients at the UW. He wears the equipment in a backpack and his fellow physicians at Harborview Medical Center, where he is now assigned, refer to the low, clicking noise of the machinery as Dutton’s “crickets.”

“It’s easy for me to forget about it when I get busy,” he says about his nightly nutrition regime. Although he rarely feels hungry, missing a day of HPN leaves him feeling somewhat “dry.” Nevertheless, about twice a month he takes what he calls “mental health days” and skips the whole process.

Dutton can, and does, eat just like everyone, but it’s a social and psychological experience rather than a source of nourishment. He generally eats something every night when he gets home from work “just as a break.”

“It amazes me how well it works,” says Dutton about his treatment. “I was so sick, so weak. It still amazes me.”

Dutton could say that he owes not only his M.D., but his life to the UW. He was in constant pain and weighed a scant 80 pounds when he arrived in Seattle 15 years ago to undergo a then-experimental treatment called “total parenteral nutrition.” (The designation “home” was added when the equipment was simplified to the point where patients and families could perform the procedure outside of the hospital.)

A few months earlier Dutton, who was then a 19-year-old junior at the University of Oregon, had suddenly experienced nausea and abdominal pain whenever he ate. At first, he blamed the dormitory food. Unfortunately, the real culprit turned out to be a chronic obstruction in his digestive system that had halted his body’s ability to absorb food.

His weight in a steep decline, Dutton dropped out of school and went home to Bend, Ore. Fortunately, Dutton’s local physician had taken postgraduate training at the UW and was aware of the “artificial gut” work being done by Dr. Belding Scribner, Dr. Alan Chait and other researchers at the UW.

Scribner has been recognized across the world for his pioneering work in the field of kidney dialysis through the use of a shunt. Although UW researchers did not invent the artificial gut, Scribner, Chait and their colleagues made significant refinements to the process. UW scientists also spearheaded efforts to teach patients and their families to perform the process themselves, outside of the hospital. “The UW was one of the leaders in helping to bring it home,” says Dutton.

Dr. Jeffrey Dutton, ’86, ’91. Photo by Mary Levin.

Back in 1976, Dutton’s physicians hoped the tube-feeding would be a temporary measure, keeping him alive until his digestive system resumed its task. It was not to be. Today Dutton estimates that he’s one of about 5,000 people in the United States using the artificial gut on a long term basis.

Blockage in the shunt or an infection—such as the one that knocked him out of training for the 1991 New York Marathon—is a continuing worry. “They try antibiotics but usually that doesn’t work and they have to pull out the line,” he explains. Removing and replacing the tube requires surgery, followed by a couple of days off work. Unfortunately, scars from previous lines leave fewer and fewer places to attach new ones. “In the long run they run out of spaces for these things,” he explains.

Less than a year after treatment began, with his weight back to 110 pounds, Dutton returned to classes at Oregon, where he earned a degree in biology in 1980. Initially, he put his degree to work in the pathology laboratories at the UW. When that environment proved to be an infection hazard, he returned to the classroom and earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology at Washington. That, in turn, sparked his interest in psychiatry which, ultimately, led him to medical school.

Because Dutton’s disability isn’t immediately obvious (the shunt is covered by his clothing), few of his teachers and classmates knew there was anything unusual about him. The few faculty members who knew of his condition were supportive. “It took tremendous determination on Jeffs part to overcome the emotional and financial burdens of his treatment in order to finish college and medical school,” notes Scribner about his former patient.

Now that he has graduated, Dutton is willing to tell his story to enlighten and encourage other people. “My aim is for physicians and patients to think of HPN therapy as a nuisance rather than a tragedy.”

Would he have become a physician if he had never been ill? Dutton’s not sure. A biology major, he was thinking about a career in the health care field. But, he adds, his parents are working class people and neither has a college education. “The mention of medical school would have probably brought the response ‘We can’t afford it,’ ” Dutton reflects.

Whatever led him to become a physician, he’s learned something from his personal experience with illness. “I know what it’s like to sit in a hospital forever and be bored to death,” he points out. He also knows something about the balance between dependency and getting on with your life. Dutton has high praise for his parents, who supported him when he was desperately ill but were wise enough to know when it was time “to let me fly again.”

But, Dutton notes, he and others with disabilities can find their wings clipped by a number of things—including the inflexibility of government bureaucracy and the problem of paying for their continuing care.

“People start out as sick as heck and then get their health back but they can’t get insurance,” he observes. So they are condemned to depend on state and federal assistance, which they risk losing if they go to work.

Beyond that, he cautions, living on disability benefits can be seductive. Dutton himself once lived in subsidized housing in Seattle’s Yesler Terrace and state vocational rehabilitation funds helped pay for his psychology degree. Even close friends discouraged him from applying to medical school, reminding him that, after all, disability programs are designed “for people like you.”

They misjudged him. “I listened to myself, I knew what I could do,” he says. “You’re lucky if you have a goal, something you get a kick out of.”