When the queen came to the UW

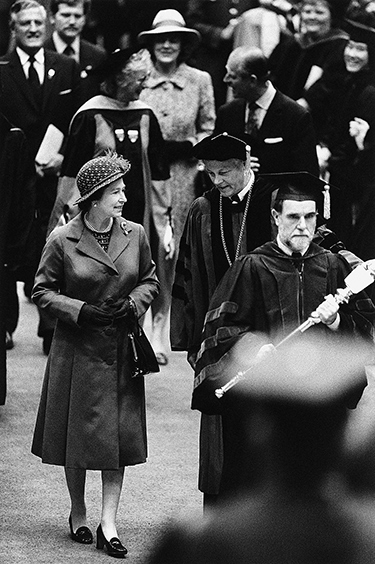

UW President William P. Gerberding (center) chats with Queen Elizabeth as he escorts her down the main aisle in Hec Edmundson Pavilion during her UW visit. Photo by Greg Gilbert, The Seattle Times.

The demand for tickets was extraordinary, comparable to a Final Four basketball tournament. Preparations were made with Scotland Yard and the Secret Service. Some 8,500 spectators filled a transformed Hec Edmundson Pavilion amid red carpeting, mammoth British and U.S. flags, white chrysanthemums, and numerous living trees native to the Northwest. More than 500 faculty dressed in their alma mater’s robes entered the pavilion followed by the sound of trumpets announcing the much-anticipated visitor and her escort, then UW President William Gerberding.

For a campus that had seen U.S. presidents, rock stars and Hollywood icons, it was still a momentous occasion. Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip were coming to the UW on the last stop of a 10-day West Coast visit to the U.S.

“We were flattered,” says Gerberding. “It was a great honor for the UW.”

On March 7, 1983, Queen Elizabeth spoke to students, faculty and presidents of the state’s four-year colleges and universities about the lasting ties between the United States and Great Britain. She even told a joke about the “Pig War,” a conflict between the two countries that started over a stray pig in the San Juan Islands in 1859. She said, “Such conflict seems impossible today,” adding that she was sure “the people of our two countries will be able to transcend the problems of the future.”

“She was very gracious and very patient; even more shy in a public setting than I had expected,” recalls Gerberding.

The event attracted media from around the world and the UW employed extensive security to ensure the queen’s safety. The Secret Service trained the University of Washington Police Department on how to handle dignitary visits. UWPD officers also completed a two-week training course with the CIA.

“One thing we had going for us is we are used to dealing with large crowds where the average police department isn’t,” says former UWPD Chief Mike Shanahan, who ran the department in 1983.

Along with the UWPD, numerous federal and state officers were on hand to guarantee the queen’s protection. The officers took precautionary measures such as keeping the doorways clear in case of an unexpected need to exit the queen safely. Even in the waters surrounding her 412-foot yacht in Elliott Bay, divers made certain there was no threat of danger.

One of the most significant public events in the history of the UW didn’t come without apprehension, but it “came off without a hitch,” says Jim Collier, who was vice president for university relations at the time. Some two-dozen IRA sympathizers waiting outside the pavilion protested peacefully, yet the queen never saw them.

There was a remarkable sense of calm in the pavilion, undoubtedly aided by the queen’s reassuring and relaxed demeanor, Shanahan remembers. The monarch commanded the audience’s attention and seemed to be having as good a time as the thousands who came to see her.

For a while, as a sign of her comfort, she even used “I” when referring to herself. “I am delighted that at last I have been given the opportunity to visit the other Washington, and particularly the city of Seattle,” she said. But in the end, protocol and tradition took over, as she concluded, “We have had a wonderful and enjoyable journey.”