With major projects on the horizon, UW relies on community spirit

That sound you hear rumbling through the University of Washington and the Seattle neighborhoods that surround the campus? Could it be the collective grinding of teeth by the 50,000 people who live within a mile of the UW, and the 50,000 or so UW employees, faculty and students who populate the campus? The reason? The region is going to be hit with three of the messiest, biggest-impact projects ever—and all at about the same time.

Brace yourself:

- Light rail is coming.

- The Seahawks will play at Husky Stadium in 2000 and 2001.

- The UW could build up to 3 million square feet on campus over the next 12 years.

In other words, life in and around the UW could be a total headache. For years. Consider: six years of construction (beginning in late 2000) on a subway line on the campus side of 15th Avenue N.E.; 71,000 Seahawk fans jamming into Husky Stadium on Sundays in the next two autumns; and a cornucopia of construction projects—ranging from the new William H. Gates Hall for the law school to possibly putting a lid over Pacific Avenue N.E.—to accommodate 10,000 more people on campus in the next decade.

“It’s pretty overwhelming,” says Louise Little, ’81, president of the Greater University District Chamber of Commerce and personnel director at the University Book Store.

Yet, despite the coming disruption, there is a strange feeling permeating these parts. For the first time in recent memory, the UW and the surrounding neighborhoods have been acting, well, neighborly toward each other. Years of rancor, mistrust and suspicion seem to be subsiding.

And just in time, too.

Oh, things are not perfect. There are still lots of ongoing squabbles. “But the situation is much better than it used to be,” says Steve Sheppard, ’71, supervisor of the Neighborhood Programs Division for the city of Seattle, who for years has been involved in dealings between the University and surrounding resident groups.

Perhaps the best example of how relations between the University and community have changed was the stunning resolution of a potentially nasty situation—the siting of a new UW indoor athletic practice facility. It looked like yet another big University-community battle.

The $26 million facility will be about 80 feet high and 150 yards long, holding about 95,000 square feet. The original site was north of the IMA Building parallel to Montlake Boulevard. But fearing it would create a “canyon effect” down the busy thoroughfare (because of the hill on the other side of the street), residents declared it unacceptable.

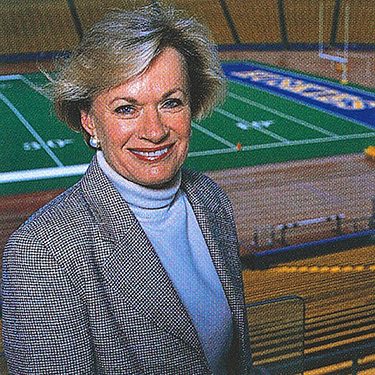

Just as tempers were beginning to flare, Barbara Hedges, the UW athletic director, turned out to attend several community meetings to see how the situation could be worked out. Her mere presence at those meetings blew many people away.

UW Athletic Director Barbara Hedges heeded community concerns by coming up with an alternative site for a new indoor practice facility, even though it will cost more and delay the project. (Photo by Kathy Sauber)

“Community concerns are of great importance to us all,” she explains. “It became very apparent to me that the concerns of the community regarding the site were much greater than anyone had anticipated. I listened very carefully to what they were saying to us.”

So she went back to the drawing board and came up with a new site on the Lake Washington waterfront behind Husky Stadium. That alternative site will cost the athletic department approximately $2 million more and delay the project by a year because construction near the shoreline prompts environmental concerns. But the UW gets the facility it wants, and preserves harmony with the community.

That move generated such good will that community organizers have begun writing government officials in support of the UW’s application for permits in that sensitive wetland area.

The solution of this matter has been hailed in all quarters. “This solution is very symbolic,” says Sheppard. “People listened. That made for a tremendous change in University-community relations. It built trust and understanding. The people involved learned they could talk, listen and work things out, even if the answers weren’t quite what they wanted to hear.”

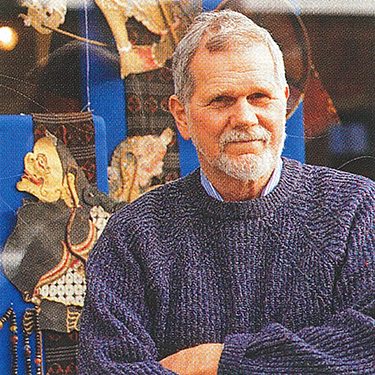

For many years much of the talking between the two sides was not exactly friendly. Bad feelings started back in the 1950s and 1960s, when communities felt the University and city were in cahoots to make sure the UW could gobble up all the land it wanted along Portage Bay so it could expand. Those moves generated lawsuits and a distrust of the UW that lingers to this day. “There’s always been the feeling that the UW would buy up more land to preserve the sylvan feel of campus,” says Fred Hart, proprietor of La Tienda, a shop on University Way N.E. “The University is here to provide education. It should not be looked at as a national park.”

“U” District businessman Fred Hart says the UW’s neighbors have long worried that the UW would buy up more land to preserve the sylvan feel of campus. (Photo by Jon Marmor)

Those hard feelings run the gamut, from legal action and threats to stop the expansion of the UW Medical Center and keep the UW from developing the Southwest campus to ongoing clamor to tear down the four-foot-high concrete wall bordering the campus side of 15th Avenue N.E. Just about everyone agrees that wall is an affront to those living and toiling outside the lush campus environs. “That wall is psychological as well,” says Hart. “It’s part of the unfriendliness of the campus, a little thing that shows the University’s attitude and insensitivity to those outside.”

Getting along has always been a prickly proposition here, given the number of players involved. There’s the University. The city. Community councils from Montlake, Ravenna Bryant, University District, University Park, Wallingford and Laurelhurst. There’s the Greater “U” District Chamber of Commerce. Various other quasi-governmental councils, and, last but not least, the 50,000 residents in and around the campus. All have their own interests at stake.

The first attempts at ironing out the cantankerous relationship between the University and surrounding communities began to take shape in 1976. That’s when the city of Seattle and the UW forged a Memorandum of Understanding to create a committee that would serve as a “viable mechanism for information dissemination and citizen input” and help put a stop to increasing enmity between the University and surrounding communities.

As a result, the City University Community Advisory Committee—known as CUCAC—was born. A coalition of 16 members from seven community councils, UW administrators, faculty, students and a city appointee, it was set up to advise the city and University on the orderly physical development of the University, adjacent community and business areas, and protect those areas from adverse effects of University and city actions.

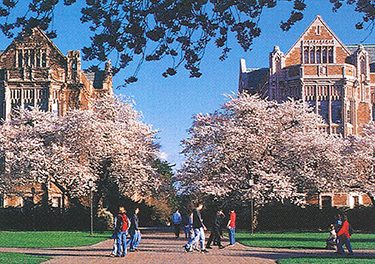

CUCAC has opened a line of communication between the parties, and is playing a vital role in the UW’s current Campus Master Plan, a document that proposes adding 3 million square feet in new buildings and physical refinements in and around campus for the years 2002-2012.

The proposed development responds to the forecasted growth in student enrollment, and is comparable to the physical development that has occurred on the Seattle campus during the past 10 years.

New buildings aren’t the only potential result of the Campus Master Plan. Planners are looking for opportunities to strengthen connections between central campus and other areas both on campus and in the community. One such idea under consideration is putting a “lid” on Pacific Avenue N.E. to treat the busy street as a “seam,” rather than a break between sections of campus. Planners also want to create more inviting campus edges and entrances and seek to do such things as make better use of the Campus Parkway area by improving traffic and circulation, and improving the quality of open space and the image of the University.

A major component of the process is keeping communities apprised of what is being considered and to solicit neighborhood input.

“We want to make sure nothing stands in the way of getting reaction from anyone,” says Theresa Doherty, the acting campus master plan coordinator. “We want an open dialogue.”

Once accused of making expansion plans behind closed doors, the UW tries to get the word out about its plans or get input. During every phase of information gathering, the UW has provided brochures, newsletters, fact sheets, frequently-asked-question sheets, Web sites, press releases, maps, as well as held meetings both on campus and at local community centers.

In June, the UW took CUCAC members on a bus tour of campus to point out 68 potential development sites. The year before that, local residents were invited to campus for a formal luncheon, featuring a string quartet, as a thank you for working so well together.

“We have worked very hard to transform our relationships with the community,” explains Bridgett A. Chandler, the UW’s assistant vice president for regional affairs. “It’s a tall order. We are growing. The communities are growing. Traffic is getting worse.”

The UW is preparing a new Campus Master plan to preserve campus beauty, such as the “Quad” seen above, while adding up to 3 million square feet of new and remodeled buildings. (Photo by Kathy Sauber)

Ah, traffic. Without a doubt, that is the biggest sore point for everyone. It’s no surprise the surrounding communities are quite nervous that the UW plans to have 10,000 more people on campus in the next decade to accommodate the “baby boom echo.” (Only a few thousand of that number are new students. The rest will be faculty and support staff.)

“The community is worried about how we can take that many new students and faculty without impacting the surrounding areas,” says Peter Dewey, the UW’s transportation manager. “Mostly in terms of traffic.”

Despite the projections, one of the University’s primary goals in the master plan is to keep car trips to campus at the same level they were in 1989. “That puts the onus on us,” Doherty says. “I know it is ambitious,” Dewey says, “but the alternatives are worse.”

The UW already made incredible strides in reducing traffic in the “U” District with its fabulously successful U-PASS program, which provides members of the campus community with incentives and options for getting to work and school other than driving alone. Students, faculty and staff purchase the U-PASS for a nominal fee, and enjoy riding public transit, carpools, vanpools and reimbursed night rides home. From 1989 to 1998, while campus population increased by 5,000, the number of automobile trips to campus decreased by 3,000.

To keep those car trips down, the UW plans to raise on-campus parking rates, foster more telecommuting, and encourage people who live near campus to walk or ride a bike. (Surveys show that the single biggest reason for people not bringing a bike to campus is their perception that there is no safe and easy bike path.)

Transportation has been a chronic sore point, but nothing has generated the level of anxiety as the coming of Sound Transit, the regional transit authority that intends to build a light-rail line connecting the University District with SeaTac International Airport. Once it selected 15th Avenue N.E. as its underground route through the “U” District, a huge debate raged: which side would the stations go on? This turned into a real hot potato, as neither the west (business and residential) nor the east (the University) sides wanted them. Placing the line on the west side might require the tearing down of such buildings as the UW Alumni House, Bartell Drugs on the “Ave” and the venerable Malloy Building apartments. Placing it on the campus side means tearing up the greenbelt along 15th Avenue N.E. Stations up to five stories tall would eat up precious campus land meant for landscaping, open space or education.

In the end, Sound Transit decided to spare the business community and place the stations on campus. Although the UW has always been a major proponent of mass transit, the decision did not sit well with UW officials. They have grave reservations about the construction of subway stations on campus, where the impact of construction and regular use could harm sensitive scientific research labs and instruments and disrupt the UW’s mission of teaching, research and service. Negotiations to soften that impact are continuing. Under state law, the Board of Regents has the final say on what happens on University property.

There are myriad issues beyond which side stations will go. They include station security, having the light-rail line terminate at N.E. 45th Street (instead of the Northgate shopping mall) and drawing potentially thousands of people into an already jammed area, and, last but not least, how to get rid of the tons of dirt that will be dug up to create the line. (For the record, a debate on that still rages. Sound Transit wanted to truck out dirt via 15th Avenue N.E. and N.E. 45th Street, while the UW—with community support—is lobbying hard to have it removed via barges on Portage Bay.)

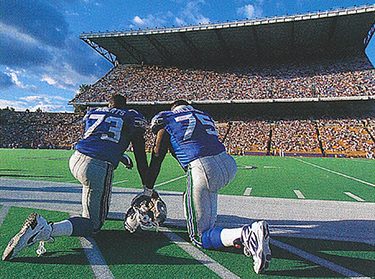

The Seahawks played five games at Husky Stadium in 1994. They will play the 2000 and 2001 seasons there while their new stadium is built. (Photo by Corky Trewin)

At the same time this was under way, hackles were raised regarding the arrival of the Seahawks, who will play at Husky Stadium in 2000 and 2001 while their new stadium is being built on the site of the soon-to-be-toast Kingdome.

With no other place to go, the Seahawks turned to the UW to see about playing at Husky Stadium, just as they did in 1994 when the Kingdome was closed for five games for emergency repairs. The University has tried to be a good citizen all around, accommodating its NFL neighbor and working diligently with the Seahawks to ensure the impact on the Montlake neighborhood will be minimal. Alcohol sales at Seahawk games are prohibited. No Monday night games are permitted. Season ticket holders will get passes for free Metro bus rides at local park-and-ride lots. All in all, the impact could be surprisingly mild.

But that doesn’t mean local residents were happy to see the Seahawks returning. Angry citizens formed a group called Neighborhoods Enduring Seahawk Impacts, which reviewed environmental impact statements, and met regularly with city, Seahawk and UW officials to make sure their neighborhoods didn’t take the brunt of the impact of the NFL team’s temporary new home.

Ironically, while those in Montlake cringe at the prospect of the Seahawks coming, just a mile to the north, others see Seahawk games at Husky Stadium as a glorious opportunity. “What we need to do is find a way to get those 71,000 fans up to the “U” District to shop,” says Hart, the La Tienda shop owner and next year’s president of the Greater University District Chamber of Commerce. “We need to take advantage of this opportunity to have 70,000 more potential shoppers on our doorstep.”

While things overall are improving, there are still hard feelings about the University. “I have lived here all my life, I went to the UW, but the “U” is not a good neighbor,” declares Judy Foss, ’69, who lives in Laurelhurst just down the waterfront from Husky Stadium. “There are huge problems with the University building baseball fields, soccer fields and this proposed indoor practice facility on landfill in Portage Bay. That used to be a garbage dump. An earthquake could be a real problem. The Urban Horticulture Center is built on a peat bog dump. What if an earthquake hits?”

“And the University is first and foremost a university. Why would it even consider having the Seahawks play in Husky Stadium? That is going to make our neighborhood a nightmare. The “U” is supposed to be dignified and not have an emphasis on making money off pro sports.”

But the UW’s role as a neighbor has been appreciated more and more. Ave activists cheered the relocation of KUOW’s offices into the old JC Penney Building on the Ave because of the stability and prestige it brings. When 11th Avenue N.E. was torn up last summer for construction, the UW allowed Metro to park its buses in campus parking lots. The UW College of Architecture and Urban Planning will be involved in a facelift and redesign of the beloved University Heights Center for the Community’s grounds. And when Chris Curtis, ’73, started up the University District Farmers Market back in 1993, she benefited from the help of students in the public relations and marketing program at the UW School of Communications. Her farmers market is now the state’s largest.

“While some people have felt the University couldn’t be trusted,” says Patty Whisler, who heads up The Ave Planning Group, an organization devoted to improving the area adjacent to campus, “there’s a lot more understanding of the University as a benefit to the community, and to our lives.”

“In the past,” adds Chandler, “neighborhoods were afraid of us as the 800-pound gorilla that was going to expand beyond our boundaries. But now we talk about being partners, of understanding each other, and creating situations where we both win.”