Letters: Story about racism was ‘a painful reminder of what happened to me’ Letters: Story about racism was ‘a painful reminder of what happened to me’ Letters: Story about racism was ‘a painful reminder of what happened to me’

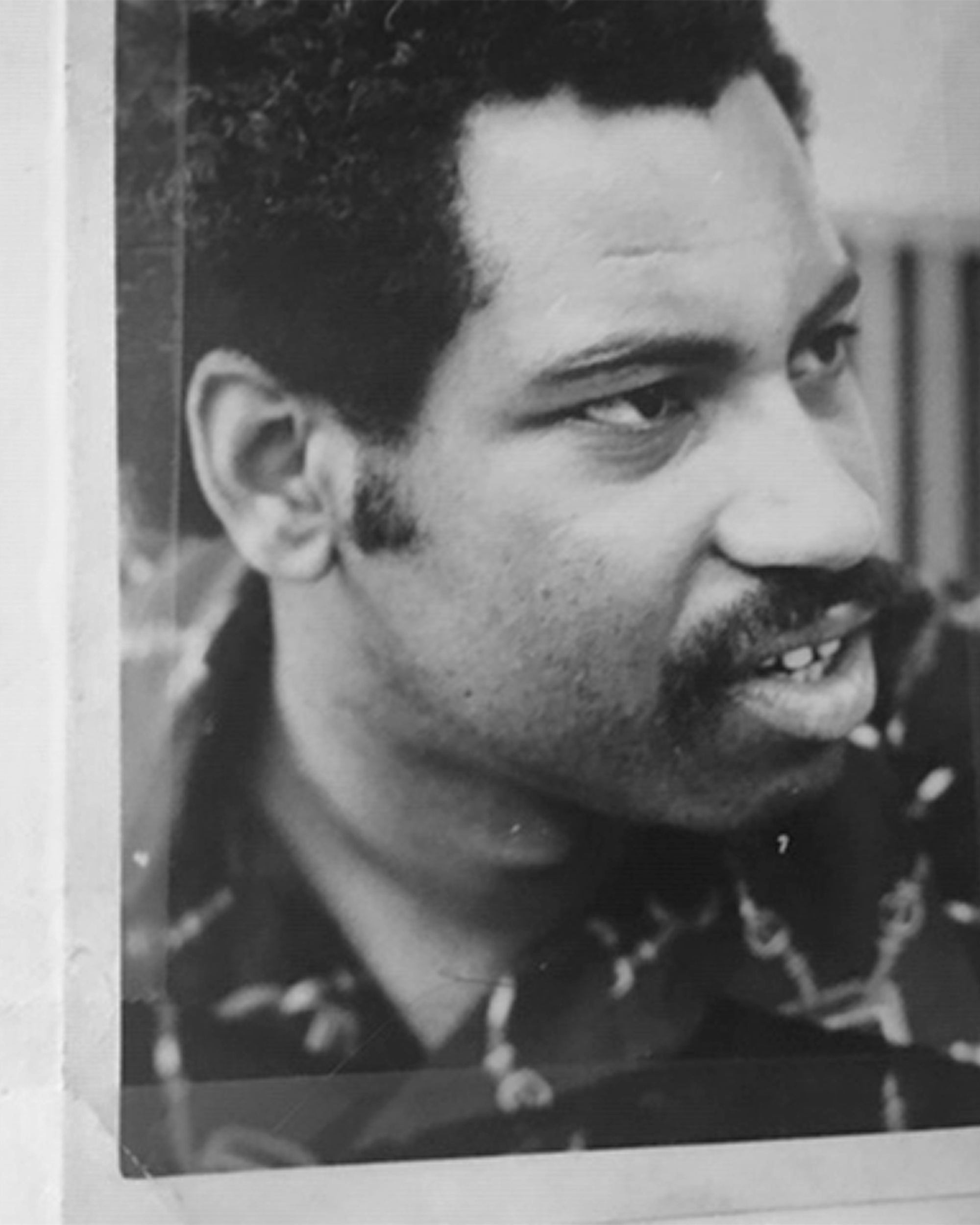

By Frederick H. Lowe, ’72 | August 26, 2019

Frederick H. Lowe, a 1972 grad who became a lifelong journalist, was prompted to share his experience with racism after reading our story “The Great American Barrier” (June 2019), which is about a black man being asked to leave a Kirkland frozen yogurt shop because his presence frightened employees.

The Great American Barrier was a painful reminder of what happened to me. I am a native of Tacoma and a 1972 graduate of the University of Washington Seattle.

After graduation, I drove my red Karmann Ghia with a canvas suitcase strapped to the luggage rack to Pittsburgh to take a job as a reporter for The New Pittsburgh Courier, a weekly newspaper. I rented a room with a shared kitchen and a shared bathroom at 342 Craig Street.

I had only lived there a month when I decided to walk to Carnegie Mellon University to attend a Donald Byrd concert. I was a block from my house when a police patrol car pulled up behind me, and another policeman in a squad car slammed on his brakes in front of me, cutting off my path.

One of the cops demanded to see my identification, which I showed him. The ID included my New Pittsburgh Courier press pass and my Washington State driver’s license.

My identification meant nothing to him. The cop slammed me against the side of the patrol car and tightly handcuffed me behind my back.

I had no idea why I was stopped and why I was being arrested.

Once at the police station, the arresting cop pushed me into an empty cell. About thirty minutes later, he ran into the cell and began hitting and kicking me as he screamed, “I hate you, n—s.”

Several other cops ran into the cell and joined in beating me. A sergeant then ran off a list of charges. If I had been found guilty and convicted of any of the charges, I would have spent 5 to 10 years in prison.

A few weeks earlier, I had graduated from the University of Washington, which was a proud moment for my parents and me. Now, I have a white cop telling me I am nothing but a “n—r.” This was a brutal onslaught of racism. The cop had the power to kill me, and I was powerless to stop him. He could lie, and the system was designed to believe him, not me. I was living in a nightmare. I stupidly assumed my UW degree would protect me from ever experiencing such brutality. After all, I considered myself special. I quickly learned I wasn’t special in the eyes of white cops. My college degree didn’t protect me from being beaten and falsely charged with a crime.

The cop walked me to a police van behind the station. We were the only ones there and I was sure he would kill me.

Police drove me to central booking in downtown Pittsburgh. Except for two white guys, everyone there was black.

The cop drove me there at night. As the sun began to rise, the other men began to whisper the name of judge we were to appear before.

“He’s a high bond judge,” a man standing next me told me.

When I walked into the courtroom, the judge looked up saying, “Fred, what are doing here?” As a reporter, I covered his courtroom, but I was so scared I didn’t remember his name.

He saw that I had a black eye and dried blood under my left nostril. I told him what happened. He shook his head, not in disbelief but in anger.

“You are a college graduate; you don’t belong here,” the judge said. He told me to go home. I walked back and stayed in my room.

My ordeal with police wasn’t over. Cops parked a patrol car in front of the building where I lived to intimidate me. The cop who arrested and beat me held up a newspaper to hide his face as I passed by.

When I returned to court a few months later, the cop attempted to arrest me on another charge. The judge ordered him to sit down. The cop told me to “keep my nose clean.” I turned my back on him and walked to the other side of the room.

I finally learned why I initially was arrested. The police charged me with burglary although I didn’t match the suspect’s description and didn’t know the location of the house or apartment. I had lived in Pittsburgh a month, and I only knew how to drive to and from work.

The person the police were looking for was 5’8” and weighed 200 pounds. I was 5’11” and weighed 155. It didn’t matter because we were both men and we were both black. It was as though blackness itself was a sufficient indication of guilt.

Getting beaten or intimidated by the police is not an academic exercise. It is pure terrorism, and black men need a way of fighting back.