Coming soon:

The new U District

Coming soon:

The new U District

Coming soon:

The new U District

Change is coming to the UW’s front door. Here’s what it means for all of us.

By Misty Shock Rule | Photos by David Oh | December 2019

Exploring the University District and being in the thick of city life is a big part of what I came to love about attending the UW. I got up to no good with friends, I saw classic films at the Varsity Theatre, and I bought records for a buck at Second Time Around, my favorite record store.

I’m a Korean adoptee raised in a largely white community. I didn’t learn to use chopsticks until my first boyfriend taught me during one of our visits to China First on the Ave. I first tasted Korean food at a tiny spot called the Korean Kitchen, which was run by a Korean grandma and her family.

Back then, those were just new experiences. But now, I see that I was unlocking parts of myself that would form the basis for who I am today.

The U District has changed a lot in the 23 years since I came to the UW. But it is about to change even more dramatically. In 2021, a Sound Transit light rail station will open in the heart of the U District at N.E. 43rd Street and Brooklyn Avenue N.E. Light rail will transform the U District into a neighborhood that is exponentially more connected, making it a desirable place to live, work and play. Developers have taken notice, especially since the Seattle City Council upzoned the neighborhood in 2017, raising maximum building heights up to 320 feet in some areas.

Between N.E. 41st and N.E. 50th streets, west of the Ave—where building heights were raised the most—nine towers up to 30 stories high are in development or planned. Dozens of other projects are in the works across the neighborhood, ranging from townhouses to mixed-use buildings.

The University of Washington’s Campus Master Plan includes intentions to further develop the University’s campus near UW Medical Center, south of N.E. 41st Street and west of 15th Avenue N.E. to the University Bridge. The plan calls for 6 million square feet of new construction, including academic, athletic, research and office space, over the next 10 years and beyond.

Private and public development will drastically alter the U District’s skyline. Seattle’s booming economy means neighborhoods across the city are experiencing the opportunities and pain of prosperity.

All of this leaves me wondering: What will these changes mean for the unique character and community of the neighborhood I love? What scenes will form the backdrop for iconic moments in the lives of future UW students?

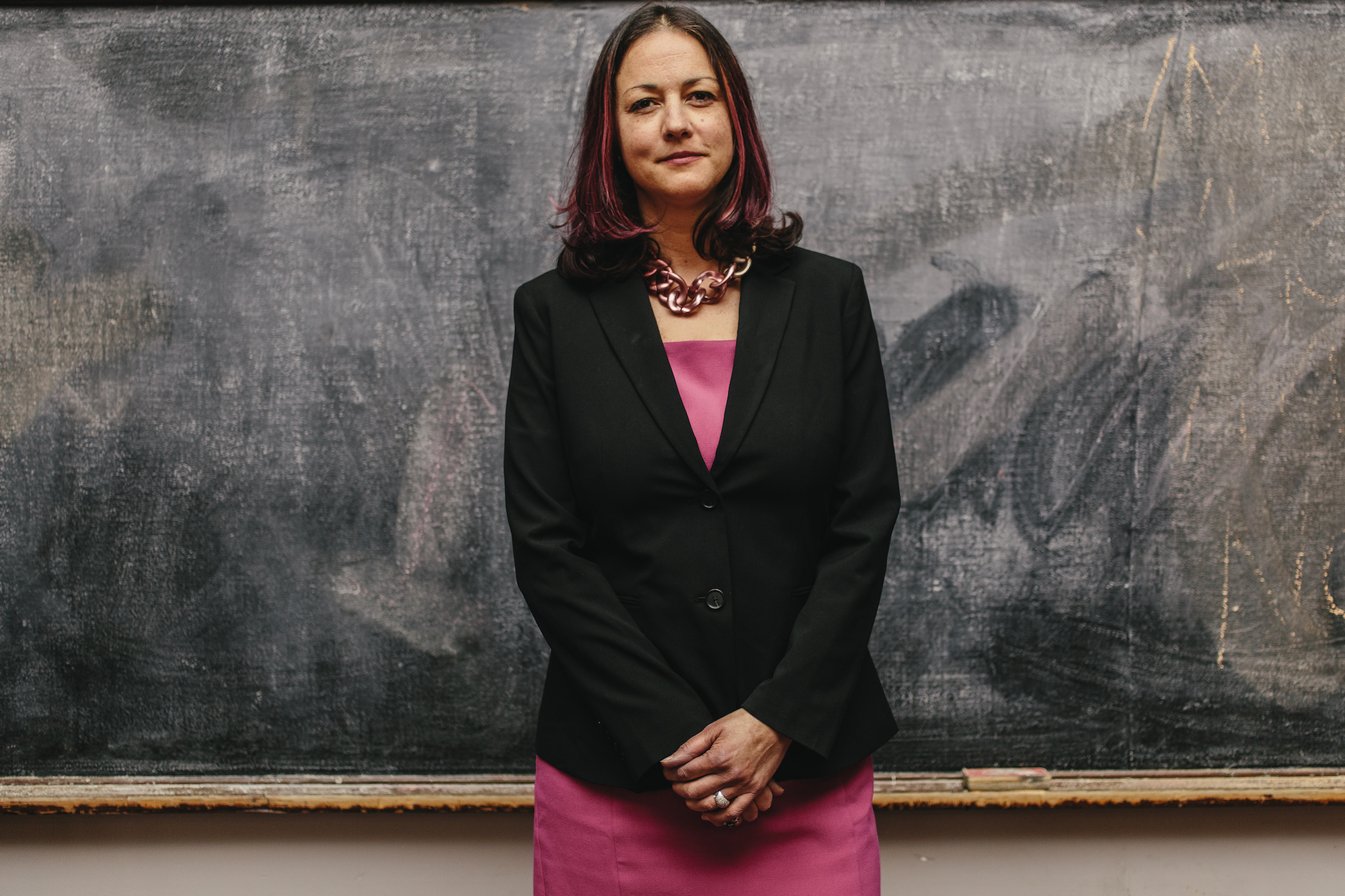

Allison Joseph, owner of Four Corners Art & Frame

Allison Joseph, ’90, has owned Four Corners Art & Frame on the Ave for 26 years. She first started working there when she was 18. She remembers coming to the Ave in the late 1980s and finding a vibrant neighborhood that drew people from all over the city. Tiny restaurants sat beside a Nordstrom Place Two and high-end boutiques like Nelly Stallion. Older people wandered down from their apartments in the morning followed by students and urban professionals as the day wore on.

“As I was buying the business, we went through a major recession. We went through the street being torn up and redone. But for some reason, my view has stayed the same. I look out my door and see Shiga’s,” Joseph says, pointing across the street to Shiga’s Imports, which has occupied the same space since 1962.

“When I open my door and hear snippets of conversation, I’ve heard different versions of the same thing for 32 years: What young people are always interested in, what old people always complain about. … The gift that the Ave gives is that you look at how difficult life can be and say, ‘Here we are all with something to offer to each other. Let’s smile at each other. Let’s hold the door open.’ ”

For many, the character of the U District is captured by the Ave, the central business district that runs parallel to the UW’s west edge. The Ave is the home to many “firsts.” Big Time Brewery, which opened in 1988, is Seattle’s oldest brewery. The U District Farmers Market is the oldest farmers market in the city, and the U District Street Fair is the longest-running street festival in the country. Founded in 1975, legendary Café Allegro wasn’t the city’s first espresso bar, but it is the oldest. Howard Schultz has described the café as a prototype for Starbucks.

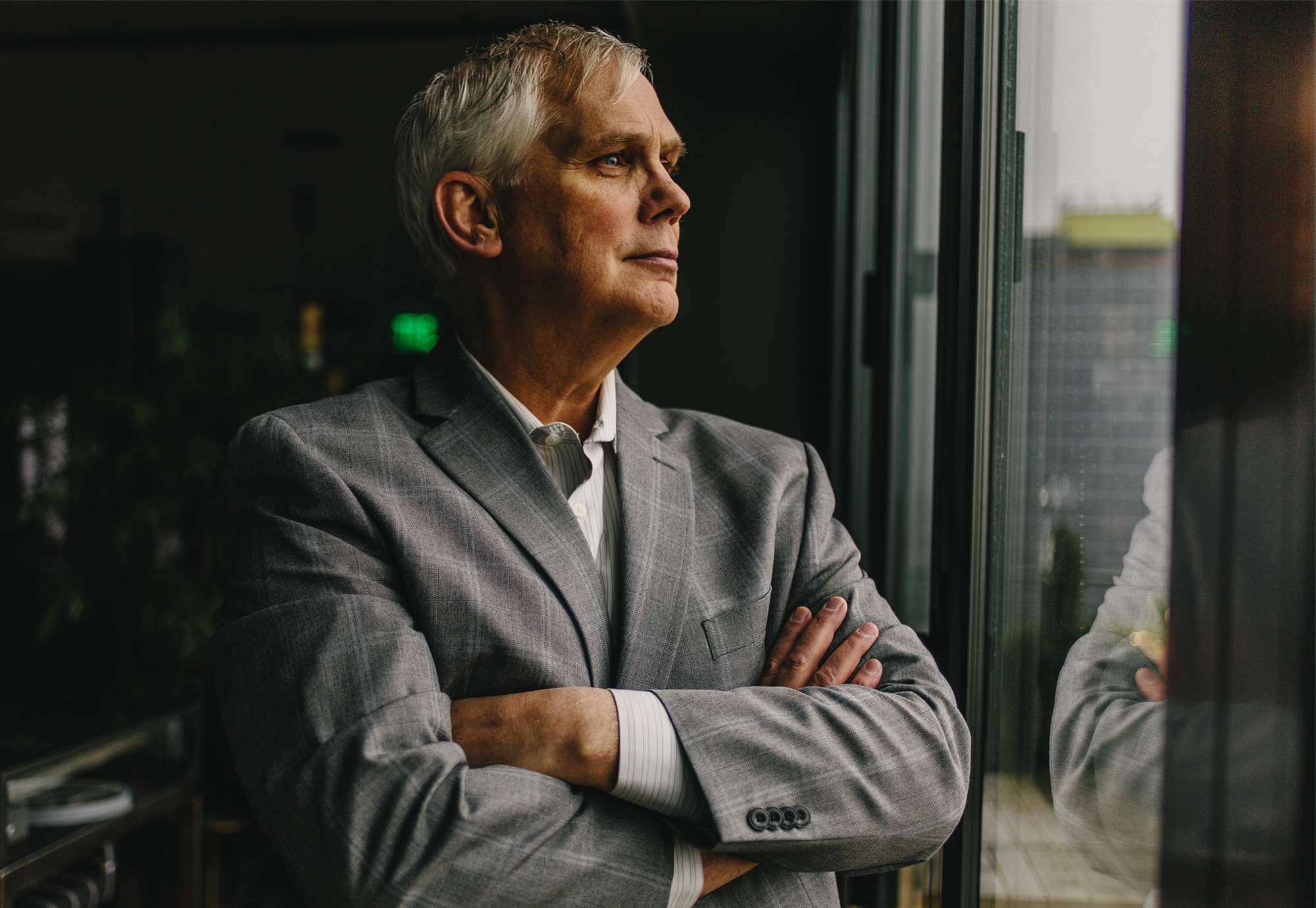

Mark Crawford, interim executive director of the U District Partnership

Much of the Ave north of N.E. 50th has already changed drastically, with sparkling new, tall buildings. And the upzone between N.E. 41st and N.E. 50th streets west of the Ave requires buildings to include retail at ground level. The nine towers planned for that area will change the U District’s commercial landscape, creating what Mark Crawford calls a new “spine” for the neighborhood. Crawford is the interim executive director of the U District Partnership, a nonprofit that represents business, residential and community interests.

“It’s a whole new economic corridor that didn’t exist a year ago,” Crawford says. “So when we think about what we love about the Ave, their monopoly is going away. The question becomes what is needed in the district to support the growing residential, commercial and employee base, and what it is that we continue to cherish about what’s on the Ave? … The district is fundamentally becoming a new place.”

Louise Little, ’81, CEO of University Book Store, is excited about the opportunities ahead. “We’re writing the story of the U District now,” she says. “I don’t think we had a compelling story 20 years ago. … You could come to theaters and you could literally eat yourself around the world. … There were fun little family-operated restaurants where you get to know the owners and meet their families and they become a part of the community. You don’t see that anywhere else. … I don’t think we did a good job of telling people what we had and why they needed to come.”

Some businesses are excited about the changes that are coming but others are worried about their place in the new U District. The conflict is coming down to the fate of the Ave. The U District Small Business Association, a collection of business owners and volunteers who want to preserve the unique characteristics of the U District, has joined with a community organization called U District Advocates to launch the “Save the Ave” campaign.

While the Ave is currently zoned for 65 feet high, most buildings are half that size. The city proposed upzoning the Ave just one story higher to 75 feet. Fearing displacement, small businesses successfully lobbied to postpone the upzone in 2017, asking for more time to study how it would affect them. In May, when the City Council upzoned 27 additional neighborhoods, it again excluded the Ave, citing the need for further analysis.

The Save the Ave campaign is fighting the upzone of the Ave. It wants to preserve its “human-scaled” environment so that it will remain vibrant, livable and recognizable. But some wonder: If developers haven’t built up the Ave already, what difference will 10 additional feet of height make?

“We’ve already given up more development capacity than any other neighborhood. Why can’t we just preserve one small section that people have a deep affection for?”

Chris Peterson, ’85, ’98, owner of Café Allegro

Chris Peterson

“Any time you raise the height limitation, you’re going to put pressure on the properties to be developed to that height because there’s an economic incentive to do it,” says Chris Peterson, ’85, ’98, owner of Café Allegro and a member of the U District Small Business Association. “I don’t think one extra floor will make that big of a difference … but there’s no guarantee that doesn’t change in the future.

“We’ve already given up more development capacity than any other neighborhood. Why can’t we just preserve one small section that people have a deep affection for?”

Peterson and other U District supporters want the Ave preserved as a historic district, citing the fact that 80% of the buildings between N.E. 41st and N.E. 50th streets were built before 1930 or are otherwise significant. In Seattle, each historic district is regulated by a citizen board. Even minor changes like exterior paint color might require formal approval.

A 2017 study by Steinbrueck Urban Strategies surveyed 123 small businesses on the Ave and surrounding areas. A large majority of businesses in the study are managed by their owners, and over half employ just one to five people. Sixty-five percent are women- or minority-owned, and 70% employ minorities, immigrants or both. Only 10% own their space, and nearly 15% are on month-to-month leases, making them more vulnerable to displacement.

At least one business, Pho Tran, decided to close after 15 years due to rising rents. Dean Hardwick of venerable hardware store Hardwick & Sons, founded in 1932, sold his property on Roosevelt Avenue N.E. to a developer for $17.2 million. He’ll continue to operate the store until summer 2020, when construction will begin on a 22-story high-rise. He will then move the business to Post Falls, Idaho, closer to his wife’s family.

Lois Ko, ’04, was born in the United States to Korean immigrants and grew up in South Korea before returning to the U.S. For 10 years, she ran the Haagen-Dazs franchise on N.E. 43rd Street and the Ave before opening her own ice cream shop, Sweet Alchemy, there in 2016. She understands the fear of other small-business owners whose landlords don’t have a connection with the area. Some landlords have even used scare tactics to bully business owners, she says.

Lois Ko, ’04, owner of Sweet Alchemy

But it’s not a fear she has. “The first time I got any wind of upzoning, I called my landlord to see what his plans were. He is so supportive of me, and he is so supportive of immigrant business owners and women business owners,” she says of her landlord, who has even offered lower rent if needed.

As a member of the U District Partnership board, she is keeping a close eye on what’s happening in the neighborhood. She keeps her neighbors informed, some of whom are immigrants who might face language barriers, and are hesitant to advocate for themselves.

“The more I’m in business,” Ko says, “the more I’m astounded by how much I need to be involved in politics.”

Sally Clark, ’90, ’04, is the UW’s director of Regional & Community Relations. When she was a UW student, she remembers that, for the University, “the end of the world was 15th Avenue N.E.”

“There was a change at some point to recognize that our students, staff and faculty are in and out of the U District every day and that UW can be a more intentional force for good in the neighborhood, ” Clark says. “You’ve seen the University go beyond 15th metaphorically in terms of being much more involved with conversations the city has sponsored around zoning and supporting efforts like the U District Partnership. You’ve also seen the University look at 15th as too much of a physical barrier and change that with new development.” Both the Burke Museum, which opened in October, and the Population Health building, which is set to open in 2020, sit right on 15th Avenue N.E. and feature more open designs integrated into the neighborhood.

The light rail station at Husky Stadium has already transformed Rainier Vista as a gateway to the UW. Likewise, N.E. 43rd Street is slated to become a major University entrance and thoroughfare between the U District light rail station and campus. The UW plans to build a roughly 12-story building above the station that will be used for office space.

If fully implemented, the Campus Master Plan will allow the University’s square footage to grow a third larger. The additional 6 million square feet will become academic, office and research space needed to accommodate 7,000-plus students and employees. It allows towers up to 240 feet high in some places and two new green spaces on the Montlake Cut and Portage Bay, including a 7½ acre park on west campus.

Half the growth will take place at west campus, which is envisioned as an “innovation district.” Legally, the campus can only be used for functions that fulfill the mission of the University, which range from traditional academic facilities, like classrooms and labs, to other uses, like housing and industry partnerships. “We’re going to try our hardest to make a really great neighborhood, a place where people want to be and where they are looking for unique, authentic experiences,” Clark says.

The City Council and the UW agreed to a provision in the Campus Master Plan for the UW to build 450 units of affordable housing for lower-wage employees. The UW had already announced a partnership to develop up to 150 of those apartments in the U District.

In 2016, 60% of U District residents were below the poverty line. In 2014, with the average rent for U District apartments at $1,241, students called on the City Council and the mayor to form a student housing affordability task force. It’s unclear if the increased market-rate housing will help relieve pressure on U District renters. Recently announced developments largely consist of high-end student housing or luxury apartments.

As part of the upzone and the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability legislation, developers must include affordable housing in their buildings or contribute to an affordable housing fund. Most opt to contribute, which means there is no guarantee of affordable housing staying in the U District.

“Part of the character of the Ave is that it does change.”

Rocky Yeh, ’01

Nancy Amidei, senior lecturer emeritus at the UW School of Social Work, has been advocating for the homeless for more than 20 years. She remembers a man named Hal, who “adopted” the Social Work building in the 1980s. He was working on a book and became part of the U District-University Partnership for Youth, an initiative Amidei helped start, and dropped by monthly meetings, took notes and interviewed people. When Hal died, one of the local churches hosted a memorial service for him, and Amidei and her colleagues took part in honoring his memory.

It’s an example of how the community has come together to care for all of its residents. “No matter how different someone might be, there’s a place for you in the U District,” Amidei says.

The U District attracts vulnerable youth because they can blend in easily. It’s common in other college areas, too, Amidei says. Sometimes, they’re even part of the UW student body. In May, a tri-campus study led by Rachel Fyall, assistant professor in the Evans School of Public Policy & Governance, found that 160 students reported that they lived in a car, shelter or “other area not intended for habitation,” and 4,800 to 5,600 students experienced housing instability at some point during the year, at the time of the study in 2018.

In response, the U District is home to services supporting homeless youth and adults. But like the residents who live in the neighborhood, those services could also be displaced.

Many services are housed in churches with shrinking congregations and rising costs. A task force convened by the U District Partnership found that more than 50% of churches providing homelessness services are at risk of losing their space. University Christian Church, which sat on N.E. 50th Street and 15th Avenue N.E., has already been demolished, displacing a dozen nonprofits.

University Temple United Methodist Church on 15th Avenue N.E. and N.E. 43rd Street houses ROOTS Young Adult Shelter, the largest shelter of its kind in Washington, and Urban Rest Stop, a hygiene center for the homeless run by the Low Income Housing Institute. The church’s property is being redeveloped into two towers, one 22 stories and the other 12 stories, which will house retail with the church below and private student housing above. Thanks to a supporter, ROOTS and Urban Rest Stop have found a home in an old fraternity house on 19th Avenue N.E., and they will move next year.

University Heights, a U District community center on the northern end of the Ave

Maureen Ewing, executive director of University Heights

“We weren’t fully appreciating the work churches were doing to keep the social safety net together. I don’t know what we’re going to do,” says Maureen Ewing, executive director of University Heights, the U District community center that offers space to nonprofits below market rate. “Who is filling the gap of these faith-based communities? The U District is the canary in the coal mine, and a city-wide assessment should be conducted to prevent further loss of critical community services.”

This September, I sat down with my friend Rocky Yeh, ’01, to get his perspective. He bought his condo in the U District in 1999, and he’s not afraid of change in the neighborhood. “The U District is ideal to become a neighborhood where you don’t need a car. This can be a transit hub of its own outside of downtown that can serve north Seattle and Ballard and points east since you have 520 right there,” he says.

“I can’t fault the upzone because the neighborhood’s supposed to be a transit corridor. It needs renewal. … Part of the character of the Ave is that it does change.”

Rocky Yeh, who has been called “a charismatic food and drinks maven,” died unexpectedly at age 42 shortly before this article went to press. We wrote an obituary for him here.

Right now, the scale of the change is still somewhat in limbo. Most of the development so far has happened in spots that were gas stations and parking lots. Ko opened a new Sweet Alchemy shop in Ballard but she is committed to staying in the U District. “The diversity of not just people, but their stages of life, who might come in because of the new housing—it will ultimately be better for our neighborhood,” she says. “I’m going to find a way to survive. I came to school here. I grew up here. I’m raising my family here. This is my neighborhood.”

I recently brought my 6-year-old daughter Penny to the U District. We ate chicken wings at Bok a Bok, the new Korean fried chicken place on N.E. 52nd Street and the Ave. Thinking back, I realized that I didn’t usually come this far north when I was a student. More businesses are populating the upper part of the Ave, no doubt attracted by the development there. Penny and I walked around wondering what other businesses would come here. There are a lot of Korean places on the Ave. I’m happy that Penny can learn about Korean food in the U District, just like I did when I first came to the neighborhood 23 years ago.