Around 5 p.m. they were ready for action. After weeks of discussions, it came down to this moment on May 20, 1968. Members of the Black Student Union (BSU) and their supporters marched into the office of UW President Charles Odegaard. As students secured the room, it became clear: they weren’t leaving until their demands were met.

Still reeling from the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, this student group felt emboldened by the Black Power movement to take control of their own destinies. They had a lot to be angry about. At the time, there were only 150 Black students on a campus of more than 30,000. No work by Black scholars was part of the curriculum. The world around them was changing, and they were determined to see the UW change, too.

By 7 p.m., the number of people in the suite had grown to 150. Supplies, food, music—even two protesters—were lifted into the third-story office by ropes. At 8:45 p.m., BSU leader E.J. Brisker, ’70, emerged from President Odegaard’s inner office with a signed document in hand.

On that day, the UW made a commitment to diversity, agreeing to the BSU’s five demands: to recruit more students of color, establish a Black Studies program, recruit Black faculty and administrators, include Black representatives in the music faculty and give the BSU a voice in decisions affecting Black students. That commitment led to the establishment of the UW’s Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity (OMA&D), which will honor that day and further efforts to advance diversity, equity and inclusion by recognizing its 50th anniversary in 2018.

What we now know as OMA&D began as the Special Education Program, run by Charles Evans, a professor of microbiology in the UW School of Medicine. It recruited and created a support structure for students who were underrepresented in the student body, based on factors like income as well as race. Its name was later changed to the Educational Opportunity Program (EOP), and EOP remains a central part of OMA&D’s suite of programs to this day.

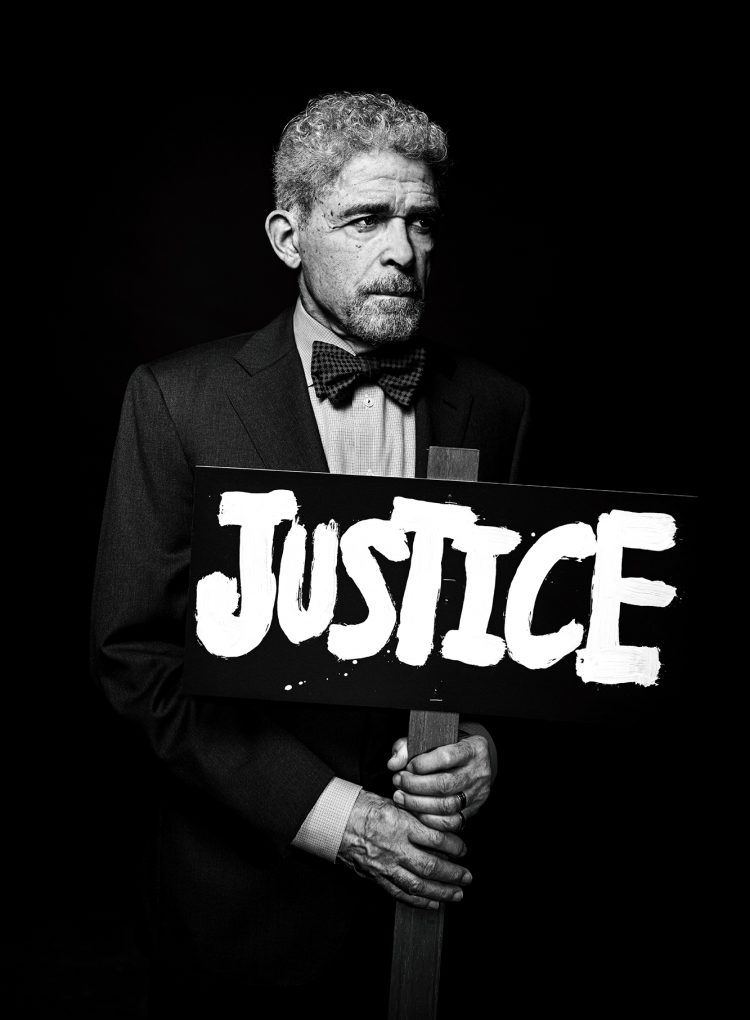

Change did not come easy. Carver Gayton, ’60, ’72, ’76, who became the UW’s first Director of Affirmative Action Programs, was tasked with increasing diversity in faculty and staff. “It was a real challenge and took a lot of work for people to buy into the concepts,” Gayton remembers. “I’ll never forget someone from the top levels of the law school telling me about their faculty recruitment work: ‘We’ve gotten in contact with Thurgood Marshall, and he refused.’ Well, Thurgood Marshall was on the U.S. Supreme Court. There was a lot of pushback.”

As a student athlete at the UW, Carver Gayton played in the 1960 Rose Bowl. Eight years later, as an assistant coach, he resigned in protest after head coach Jim Owens controversially suspended four Black players.

When Evans returned to his job in the medical school, President Odegaard looked to Samuel E. Kelly, who wowed the President with his experience as an army officer and with his minority affairs work at Shoreline Community College. Kelly was firm that an organization, not just a program, was critical to helping students of color. He also insisted that Odegaard hire him as a Vice President with a seat on the President’s cabinet, a level of access still not granted to leaders of many diversity programs today. The Office of Minority Affairs (OMA) was born.

Sharon Maeda, ’68, was the second director of OMA’s Ethnic Cultural Center, the country’s first multi-ethnic center for students of color. When asked about Kelly, she remembers a man exacting in military discipline. She recalls, “He came to the ECC once and swiped his finger along the top of the bulletin board. He said, ‘You have to dust these.’ It was like we were all in the army.” But along with that discipline came the perseverance of a fighter. “He was dynamic. He fought for our rights at the highest levels,” Maeda continues. “We know that Dr. Kelly faced a lot of criticism and hostility from some people on faculty and in the administration.”

One of the first Black army officers to command both Black and White troops, Kelly had a talent for bringing people together. He led OMA at a transformative time in Seattle’s history, with cross-cultural collaborations by activists like the Gang of Four, which included BSU founding member Larry Gossett, ’71; Roberto Maestas, ’66, ’71, the leader of El Centro de la Raza; “Uncle Bob” Santos, who fought to preserve the Chinatown/International District; and Bernie Whitebear, the founder of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation.

Sharon Maeda was the director of the Ethnic Cultural Center, the country’s first multi-ethnic center for students of color.

With support from the community, a strong partnership with President Odegaard, a clear vision and tenacity, Kelly created and strengthened many of the programs that define the office today, from EOP and the Ethnic Cultural Center to the Instructional Center, which has served more than 35,000 students with academic support since 1970, and the Friends of the EOP, which has raised millions of dollars to support students since 1971. With college access programs like Upward Bound, OMA went across the state to reach students from underrepresented minority communities to share the dream of college.

Gayton credits OMA’s early success to its origins: “The student movement made an impact on the immediacy of the issues. The foundation gave a sense of urgency from the beginning for getting a Vice President and setting it up for success.” Just as it did in its early days, the office has continued to evolve to meet the needs of underrepresented minority, first-generation (first in their families to attend college) and low-income students, along with faculty and staff. In service to those communities, it has reflected our changing world, shaping the landscape around diversity, equity and inclusion in higher education and at the UW.

Magdalena Fonseca was born in Mexico. When she was a child, her father was sponsored by a farmer in Othello and brought the family to the tiny Eastern Washington community. Her older sister, the first to go to college, attended the UW. “She was bossy. She said, ‘You’re going to go to college, you’re going to the University of Washington,’” Fonseca recalls. Fonseca entered the UW as part of the EOP and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1998 and a master’s degree in education in 2011.

As she began life as a UW graduate, Washington state experienced a dramatic shift in the conversation around race. In November 1998, Washington voters passed Initiative 200. It forbids universities or any government agency from using race or sex as criteria, outlawing governmental affirmative action programs.

After earning her undergraduate degree, Fonseca came back to OMA as an office assistant. She remembers experiencing a high level of anxiety in the aftermath of I-200’s passage. “To be a young person who had just graduated, I was intrigued to see where politics meets real-world experiences,” she says. “There was the feeling that we may not be able to provide the same level of resources to our students. It was scary.”

Magdalena Fonseca entered the UW as an EOP student and has worked at the UW since 2001 as an advocate for underrepresented minority communities.

After I-200, enrollment of students from underrepresented communities dropped. UW leadership regrouped, outlining initiatives to improve diversity while complying with state law. The UW created a more holistic approach to admissions, looking at the whole student rather than just grade-point average and test scores. Working to attract a diverse pool of students, OMA ramped up its outreach efforts across the state. This included creating the Student Ambassador Program, an effort connecting UW students with high school and middle school students, and continuing work in the Yakima Valley, Eastern Washington and other areas across the state with historically underrepresented communities.

By the time Rusty Barceló stepped on campus as the UW’s new Vice President of Minority Affairs in 2001, the level of anxiety had subsided. But the crisis was not over. OMA had to adapt to survive. One place to begin was the name of the department. The Office of Minority Affairs became the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity to reflect the fact that the office serves more than just underrepresented minority students—it serves first-generation and low-income students as well.

“The University of Washington, especially around its diversity programs, is one of the country’s best-kept secrets. Everybody, from the leadership to the community to the whole campus, comes together to make things happen.”

Rusty Barceló

Under Barceló’s supervision, the office’s focus broadened to include all areas of the University, from faculty and staff—with the establishment of the Office of Faculty Advancement—to campus climate and diversity-related research, teaching and service.

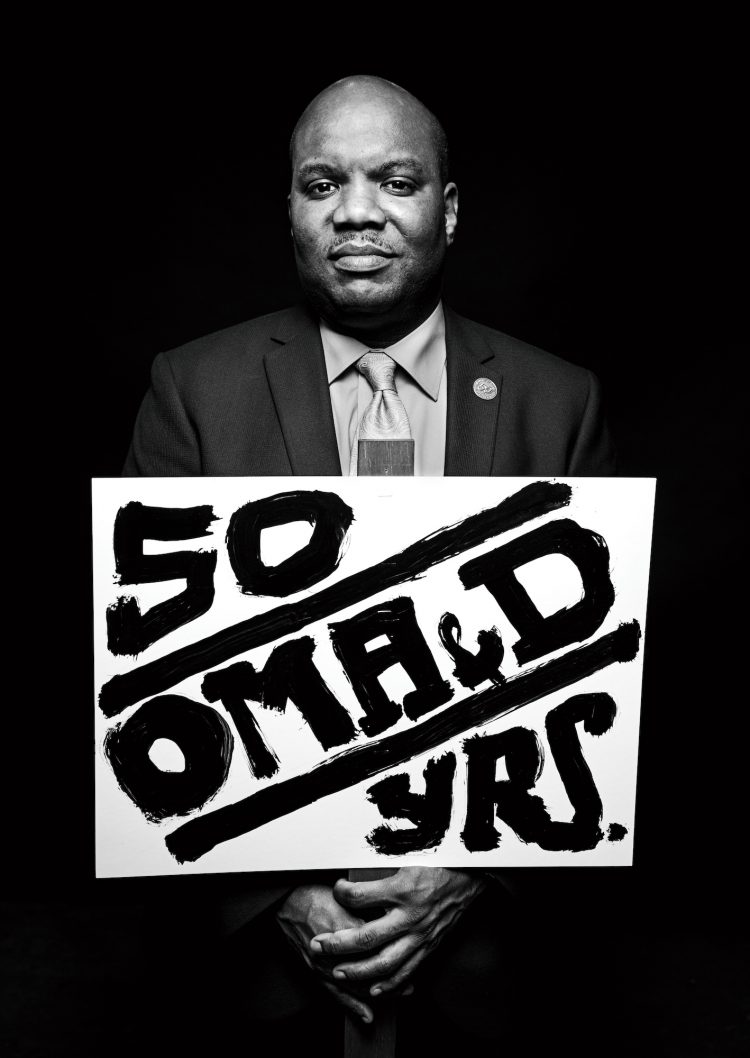

Data became a critical part of how OMA&D told its story and measured success. Emile Pitre, ’69, is a founding BSU member and was a tutor, instructor and director at the Instructional Center, before becoming OMA&D’s associate vice president for assessment. He is quick to rattle off a list of prominent government and community leaders who are among the nearly 30,000 UW graduates who were EOP students.

Emile Pitre, a founding member of the Black Student Union, occupied the office of UW President Charles Odegaard in 1968.

After a year as an office assistant, Fonseca moved to the Samuel E. Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center (renamed for the founding vice president in 2013), and she’s been there ever since. “I have known many of the people at OMA&D for over 20 years now,” she reflects. Now, as the center’s interim director, she serves more students than ever. For two years in a row, the UW has set records for the most diverse incoming class in its history.

At OMA&D, the community works together to move forward, serving 21,000 students in middle schools, high schools and two-year colleges across the state. More than 5,700 current UW undergraduates benefit from opportunities ranging from advising to community building and leadership development. OMA&D’s most recent addition, Intellectual House, provides a learning and gathering space for American Indian and Alaska Native students, faculty and staff, as well as others from various cultures and communities. Its 2015 opening was the culmination of a four-decade-long dream to build a longhouse-style facility on campus. With these efforts, OMA&D is doing work that will benefit our University and our region. As Pitre says, “You can’t advance the cause unless you have a group that’s ready to go alongside you.”

Barceló is not surprised about the heightened conversation around race today. In her career working on diversity, she has seen it play out on our country’s campuses. “There has been this quiet backlash, a retrenchment,” she observes. “I’ve seen programs like Chicano studies, African American studies being challenged across the country.

“The University of Washington, especially around its diversity programs, is one of the country’s best-kept secrets. What makes the UW so unique is how everybody, from the leadership to the community to the whole campus—not only the folks at minority affairs—comes together to make things happen.”

Across society, diversity work has historically existed on the margins, the job of someone else to figure out. Rickey Hall, UW’s current Vice President of Minority Affairs & Diversity and Chief Diversity Officer, says that time has come to an end: “In order to succeed, it has to be everybody’s everyday work. We all must lead from where we are. We all have spheres of influence. No one person is going to be able to transform the institution. It takes all of us pushing and lifting.”

Rickey Hall, Vice President of OMA&D and Chief Diversity Officer.

Building our university community is a shared responsibility. This theme is reinforced across all three campuses today with the Race & Equity Initiative, launched by UW President Ana Mari Cauce in 2015.

As OMA&D celebrates the past, it is also looking forward. According to Hall, plans for the next 50 years start in one place: with students. “Issues are ever-changing and evolving, and this office must change and adjust as the needs of our students change,” he asserts. “That’s what we’re trying to do here: make sure we are meeting the needs of our students today and students coming in tomorrow.”

The students OMA&D serves today define their identities on multiple levels, not just race or gender. They were raised with more education around these issues and have a different level of awareness. And they are outside of the traditional ethnic boundaries, like multiracial students, and other intersectional identities.

The Leadership Without Borders program, which is led by Fonseca and serves undocumented students, is one example of how OMA&D is responding to the changing needs of our student populations. With undocumented students in mind and with the mission to serve as a launch pad for students’ leadership, the program is a space for community building and a connection point for awareness, as well as resources and services.

From leadership development resources, health and wellness programming, meeting space and connecting peers, to loaning textbooks out of the Husky Lending Library, the program offers a lifeline to a group experiencing high anxiety today.

One thing is clear: the hugely successful impact of OMA&D. “Without this office, I probably would’ve dropped out,” Fonseca confesses. “If I didn’t have these spaces where I felt like people were going to understand me, I wouldn’t have stayed. I would’ve felt like it wasn’t for me, just like I believed growing up that college wasn’t for me. I would’ve fulfilled that prophecy. I will always sing the praises of the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity. I’m homegrown. And I want to give back.”