Why we 🤍 the ECC Why we 🤍 the ECC Why we 🤍 the ECC

You can organize a movement, build a community, find a campus family, find your calling or just escape from class. Four decades of alumni share their love of this place.

Interviews by Hannelore Sudermann | Viewpoint Magazine

Nine alumni tell us why they love the Samuel E. Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center, a multicultural center on campus that values diversity and inclusion for all. The interviews were edited and condensed for clarity.

♥ | Because it’s the best place on campus

When I think of mental health and things like that, I think of the ECC. It offered a place of inclusion and belonging for all of us. And when I was a student, pretty much every student of color knew every other student of color on campus. Beyond being a base for all the student associations, it was a place where successful people in the Hispanic community—like engineers at Boeing—could connect with us. They would come out and feed us during finals and bring us presents during the holidays. Those were like family gatherings. It was also one of the places the off-campus community felt they had access to connect with students.

Within the students, every group did something special, and we were all part of it. The Hawaiian students, for example, held luaus. The building during my time as a student was run down. It was not the nicest place on campus, but it was the best place.

—Roy Diaz, ’94, ’96, ’02, is an intellectual property lawyer and former president of the UW Alumni Association.

The view inside the ECC. The mural seen at the top, “Bearers of Culture,” was painted by Eddie Ray Walker, co-founder of the ECC.

♥ | Because it is a different world

I grew up on the Yakama Reservation and came from White Swan High School in Yakima. My graduating class was about 36. My first class at the UW had over 200. It was culture shock. Without the ECC and the Minority Scholars Engineering Program, I don’t think I would have made it through. At first, it was mostly tutoring at the Instructional Center across from the ECC four to five days a week, and later the ECC became place for socializing. Though the engineering program had hundreds of students, only two of us were Native American. It was lonely. The ECC offered a different world. It was the one place I could see another Native American. A couple of my friends were always there no matter what time of day. If someone wasn’t there, they would be showing up soon. My experience with the ECC is one of the reasons I became so involved: I was president of the chemical engineering student organization, active in First Nations at UW and the first student to participate in OMA&D’s ambassador program. It’s why I’m working with students now. It’s why I’m mentoring them.

—Jerald Harris, ’01, is a citizen of the Chinook Indian Nation. He works as a mentor and enrichment coordinator with students in he Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde.

Photo by Sophanna Tes, ’19

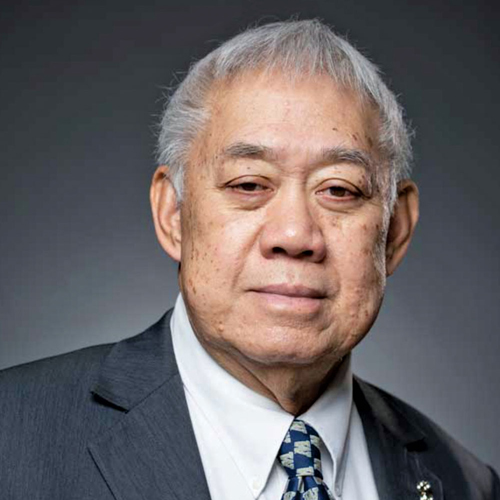

Frank Irigon

♥ | Because you can do big things there

We took over a community newspaper and, out of the ECC, we created the first pan-Asian publication in Seattle. It started with Diane Wong, ’72, Norman Mar, ’72, Alan Sugiyama, ’84, and me. I remember meeting at the ECC to name it. We had a number of ideas and someone brought up the song by Sly and the Family Stone, “Family Affair.” We took that and created “Asian Family Affair.”*

We would meet up at the center on Saturdays and Sundays and did everything by hand. Sometimes we would have to ask the campus police to let us in on the weekend. We had an IBM electric typewriter and we wrote up and laid out the paper, putting together all the stories and pictures. The University afforded us that space to publish a newspaper and tell stories no other local media would produce. We wrote about Alaska Cannery Workers and Executive Order 9066, the 1942 order that led the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans. We interviewed Patsy Takemoto Mink, the first woman of color elected to Congress, and George Takei, actor and activist. We were pushing to highlight Asians in public roles.

None of us were paid. The newspaper was a labor of love for our community and need for getting the news out. A lot of us were going to school and the ECC was close. Without being able to start it there on campus, I don’t know how long we would have been able to stay focused. At the ECC we had nurturing environment. It was a place where people could have different points of view and still get along.

—Frank Irigon, ’76, ’79, lifelong activist and co-founder and onetime executive director of the International District Community Health Center. Recipient of the 2022 Charles E. Odegaard Award.

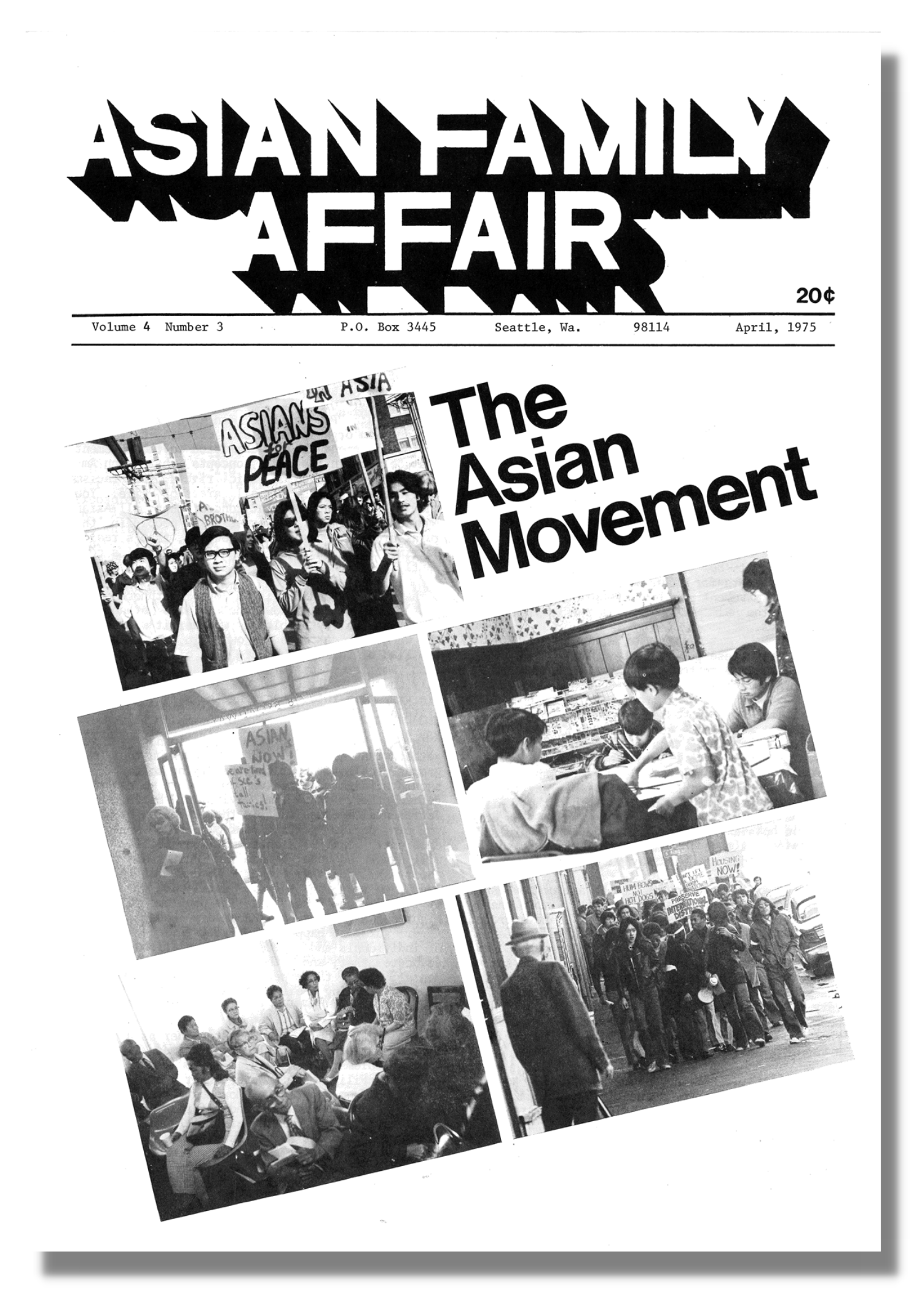

*In 1972, Asian American and Pacific Islander students developed Asian Family Affair, the first pan-Asian newspaper in the Northwest. The hardworking team of journalists tackled topics including labor disputes and neighborhood preservation and women’s rights. They did this work out of the Ethnic Cultural Center.

In 1975, the Asian Family Affair, a newspaper produced by UW students for readers in Seattle’s Asian American community, turned its focus to Asian American rights, activism and community experience.

Tiffany Dufu

♥ | Because it’s where you can find your path

One of the most important parts of my UW experience was the leadership opportunities. I was president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and a member of the student organization called Sisterhood, which was formed by Toyia Taylor. We met in the Black room at the ECC. I spent most of my time there. In both organizations, we were committed to community service. We would go and visit a house for teenage mothers bringing clothes and gifts. It made us think about our lives and the opportunities we had and to connect with young brown women that we loved to give back to. We also mentored young women at local public schools. The experience has definitely informed my career now.

How often was I there? Every day! We lived there! I worked as a tutor in the Instructional Center across the street and then I would come over to the ECC and just hang out. At big public universities you often hear that you’re going to be lost. But as a student of color at the University of Washington, it was very personal. I felt the UW was and continues to feel so small.

—Tiffany Dufu, ’96, author of “Drop the Ball: Achieving More by Doing Less,” is a national figure in the women’s leadership movement. Her company, The Cru, focuses on advancing women and girls in their personal and professional lives.

Vivian Lee

♥ | Because it’s a base from which alumni can encourage diversity across campus

In the late 1990s, the UW Alumni Association’s Multicultural Alumni Partnership held several annual retreats at the Kelly ECC. And from 1997 to 2001, MAP developed and co-sponsored diversity summits with a student group called Multicultural Organization of Students Actively Involved in Change. The goal was to encourage campus-wide involvement in promoting diversity. MAP had a lean budget and we often provided food for the summits out of our own pockets. The large session was always held in the ECC Theater and all the breakout sessions were held in the ECC, in each of the four rooms with the ethnic paintings. The ECC and the Ethnic Theater have represented diversity just by being named as diversity places.

—Vivian Lee, ’58, a nursing alumna with a ground-breaking career in the Seattle health community, is a volunteer, advisor and activist. She mentors future nurses and advocates for students from underrepresented backgrounds. She co-founded the UW’s Multicultural Alumni Partnership in 1994 and won the Odegaard Award in 2000.

Shafiqa Ahmadi

♥ | Because it was ahead of its time

I was an Afghan refugee who immigrated here with my family in 1987. While the UW didn’t have that many Afghan students when I started in the early 1990s, I found a community of people at the ECC who looked like me. It was a great place for community building. I remember there was a TV where we would watch “Days of Our Lives” together. We also did our homework there, just sitting near other students. It was a community of scholars. Out on a campus that was predominantly white, you didn’t feel like you belonged, but at the ECC we felt understood and supported. It was ahead of its time. There were individuals who worked there who really understood students of color and the challenges we faced. It’s something a lot of institutions should be doing. A lot of what I do now is certainly informed by my own experiences at the UW.

—Shafiqa Ahmadi, a former UW student and current associate professor of clinical education at the University of Southern California. She is an expert on diversity and legal protection of underrepresented students, including Muslims and survivors of bias, hate crimes and sexual assault.

Tim Bond

♥ | Because it was home to Seattle’s first multiethnic theater

The Group Theatre was formed in the ECC’s theater back in 1978 when Rubén Sierra and 10 other people put on a play called “Short Eyes.” It was so successful, more performances were added. Once the run was done, people kept asking “What are you going to do next?” So the next play was “Steambath” about God being a Puerto Rican janitor. And people were asking, “What is your theater group called?” And Ruben said, “The Group,” and that’s how it became The Group Theatre. It was the only multicultural theater in the city and became known around the country. The Group performed plays by African American, Chicano and Asian American playwrights and cast actors of color in plays that typically had white actors. I was a student coming with a BFA from Howard University back in 1980-’81 and I read that the UW had an Ethnic Cultural Theater that was home to a professional company that does multiethnic plays. There was a fellowship especially for graduate students of color in the drama department. It attracted me all the way from Washington, D.C. It totally changed my life.

Once it formed, The Group quickly became one of the top five theaters in Seattle, it was so successful. By the time I got there in 1981, it was a professional theater that used professional actors. Rubén and I started a multicultural playwrights festival. Writers from around the country would come and workshop their plays with us. We also had a loyal season ticket-holding audience. We were a major part of the theater ecology, a place where actors could launch their careers, going from amateur to professional on their way into major careers. It was a great time for theater in Seattle.

—Tim Bond, ’84, was artistic director for The Group from 1991 to 1996. From there he worked at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival and went on to direct in theaters around the world. He returned to Seattle in 2016 to serve as head of the UW’s professional actor training program. In 2020 he became artistic director for TheaterWorks in Silicon Valley.

Photo by Sophanna Tes, ’19

Yuriana Garcia Tellez

♥ | Because you can be who you are

I’m originally from Mexico and I grew up in Eastern Washington. When I came to campus, I struggled to find any kind of support. I actually walked into the Ethnic Cultural Center and said, “I’m an undocumented student, where can I get resources?” At the time, people on campus did know there were undocumented students, but they didn’t understand how to help us. There wasn’t an active allyship. Being a freshman in a new city, keeping my grades up and dealing with financial pressures and living pressures was more than most people realized. While we had in-state tuition, thanks to House Bill 1079, we had no access to financial aid. When you walked into an office on campus, you never knew if you were able to feel welcome. Professors had no idea about our student experience. We were closeted. But I would talk to anybody who would listen about how we were underresourced.

When you make a space dedicated to students of color—people who look like me—you feel you can actually trust people with who you are. When I met Maggie (Fonseca, an ECC staff member at the time and current director), she said, “You can trust me.” It was just so important having someone to listen. Where I met barriers on campus, at the ECC they just asked, how do we help you? I think I started speaking up right away. I was the person who would just put myself out there even though I was afraid. We started a registered student organization for undocumented students and put together a fundraiser that raised $1,000 to give a scholarship to someone who was undocumented. Then we thought of holding a conference and invited regional teachers and counselors to help build a community around undocumented students. I remember that day, March 22, 2012. We were planning for about 45 people and 230 showed up. Educators and parents brought their students and children. We packed them all into the ECC. Afterwards, we heard from the students that it was a relief to learn that college was a possibility and there might be a scholarship you can apply to. Everybody should be able to lean into their lives, including undocumented students.

—Yuriana Garcia Tellez, ’18, led the Kelly ECC-based Leadership Without Borders program for undocumented students. She later worked in undocumented student services at Rutgers University. She also worked in diversity outreach and engagement for the city of Bellevue. Today, she is an inclusion recruiting program coordinator at Netflix.

Emile Pitre

♥ | Because it was planned by students for students

In the late 1960s, some of the founding members of Black Student Union attended a conference in Los Angeles to learn about establishing Black studies programs and recruiting Black faculty, students and administrators to their school. They also heard from poet Sonia Sanchez, a leader in the Black arts movement, about how celebrating culture can foster student wellbeing. They came home wanting to build a place on campus for social and cultural support and celebration. The students drafted plans for a multiethnic cultural center, a theater and a learning center and, with the help of Dr. Samuel E. Kelly, presented them to the University’s administration.

—Emile Pitre, ’69, was a founding member of the Black Student Union and later joined the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity. Over three decades working with underrepresented first-generation and low income students, his various roles included serving as director of the Instructional Center and associate vice president for assessment at OMA&D. He is also known as OMA&D’s “elder statesman” and historian.

- Photo by Sophanna Tes, ’19

- Photo by Sophanna Tes, ’19