The life and times of Daniel J. Evans The life and times of Daniel J. Evans The life and times of Daniel J. Evans

A rare pragmatist who never compromised his values, Evans bettered the world as a senator, governor, community-college builder and champion of the environment.

By Bob Roseth | December 2024

Daniel J. Evans, who often pursued a bipartisan strategy to accomplish his goals, was a lifelong Republican. However, over the course of his career his party effectively left him, abandoning most of the principles that he cherished.

He was born in 1925 and grew up in the Laurelhurst neighborhood of Seattle. His father was a civil engineer, rising to become the engineer for King County, responsible for designing and building the road system for the growing city and environs. His mother, following a family tradition, was a frequent volunteer for the local Republican Party. Political discussions were common at their dinner table.

Evans joined the Boy Scouts and achieved the level of Eagle Scout by age 16. Much later, political commentators connected his scrupulous honesty and forthrightness with those early experiences and nicknamed him “Straight Arrow.” Evans credited his scouting experiences with inspiring his lifelong love of Washington’s mountains and natural beauty.

Evans was in officer training school when World War II ended. He attended the UW on the GI Bill, received a B.S. in civil engineering in 1948 and a master’s degree a year later. He was called back to military service in the Navy during the Korean War in 1951. From the Sea of Japan, he wrote his father about his intention to seek political office when he returned home and help the country head down a different path.

A self-described sense of mission led Evans to run for the state Legislature from the 43rd district in 1956. His campaign was energized by buddies from his scout troop who volunteered to help him doorbell every house in the district, a new idea in local campaigns. He not only won but outpolled the district’s incumbents. Evans’ practical, detail-oriented approach, buoyed by a steady optimism, already was on display.

In his first session, he served on committees dealing with highways, forestry, and state lands and parks. After the session, his party recognized him as its outstanding freshman legislator and by 1960 he had become their floor leader. Colleagues and observers in Olympia noted that he was a quick study, mastering the detail and substance of ideas as fast as anyone in government.

Evans in his gubernatorial office with Assistant Secretary of State Sam Reed.

Evans’ political style was evident from Day One. When the parties were at loggerheads over the route for construction of what became the Evergreen Point Bridge in 1961, he recognized that his side didn’t have the votes for his preferred route. So he signed on as co-sponsor of the Democratic proposal, ensuring in negotiations that approaches to the bridge from eastern ramps were improved to his liking. “I still think it’s in the wrong location,” he commented, “but since it is being built, we ought to do a proper job of it.”

In 1963, minority Republicans learned that a band of House Democrats was disenchanted with their party’s leadership. Moving carefully and quietly, with Evans in the vanguard, they persuaded the dissidents to join them in a vote to oust the longtime speaker, giving the Republicans a measure of power even though they were in the minority by holding together the bipartisan coalition. The coup propelled Evans onto the short list of Republicans who might run for governor in 1964. He was ready for the challenge.

He knew it would be an uphill race. For starters, he had no name recognition outside his district. An early poll showed that statewide, he was supported by about 4% of voters. But as with his campaign for the Legislature, he out-organized and outworked his opponents, campaigning tirelessly and accumulating a growing cadre of enthusiastic and highly capable volunteers.

1964 was a bad year to be a Republican. Nationally, the party had chosen Barry Goldwater, a far-right senator, to run against President Lyndon B. Johnson. Candidate Evans distance himself from the party’s standard-bearer, and Goldwater’s assertion that “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” surely made him wince. He introduced himself to state voters as a “passionate moderate.”

The party endured an epic defeat that toppled Republican office holders nationwide. Despite the headwinds, Evans was elected with 56 percent of the vote as the only new Republican governor in the country. His agenda included addressing human needs for medical care and unemployment programs, a civil service system for state jobs, major expansion of community colleges, stable funding of K-12 education, more efficient government and a favorable climate for job growth. Evans prevailed by wooing independent and moderate voters, his approach in every election thereafter.

Evans out-organized and outworked his opponents, campaigning tirelessly and accumulating a growing cadre of enthusiastic and highly capable volunteers.

Some voters, and his right-wing Republican colleagues, were shocked when he announced that, in order to bring his plans to reality, tax hikes would be required. He shrugged off their criticism and continued down the path that he was sure was best for the people of his state. “We should take pride in doing what was right” was one of his standard replies.

While supporters and opponents were busy catching their breath, Evans augmented his agenda with yet more issues: improved transportation, curtailing pollution and reforming the state constitution.

For much of his time in office, Democrats had a majority in at least one house of the Legislature. Sometimes both. But he did not view that as a deal-breaker for his policies. He believed that many of his positions were actually nonpartisan, good for most citizens, and welcomed support from across the aisle. Advisers and even critics noted that they never witnessed him change his views for political reasons.

Dan Evans: as a briefly bearded governor in 1973. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

As a moderate, Evans was able to carve out a comfortable niche in the Republican Party of that day. But fervent opposition arose from right-wing party activists, especially in King County, which included a growing contingent of Birch Society members and sympathizers.

Evans responded in 1964 by repudiating the “irresponsible, irrational right” and demanding that the party expel extremists. “The Republican Party did not achieve greatness nor will it regain greatness by being part of the radicalism or lunatic fringe. I do not intend to watch silently the destruction of our great party and with it the destruction of the American political system,” he told a state convention.

The perennial American debate over who should be responsible for providing necessary human services and supports, the state or the federal government, was answered by the Birchers as “none of the above.” Evans concluded they were not Republicans, at least not traditional Republicans. The party ended up supporting his motion.

The move was largely symbolic as there was no way to police the beliefs of party members. Evans continued to face deep divisions within the Republican Party for the remainder of his time in public life.

As governor in the 1960s, Evans had to deal with large demonstrations and political activism against the Vietnam War and on behalf of civil rights. He responded by declining to send the National Guard to the UW campus, meeting with Black student activists, creating one-stop citizen service centers to address needs in underserved communities, and by appointing the first Black members of the governing boards of Seattle’s community college and the University of Washington. He also created the Indian Affairs Commission and the state Women’s Council.

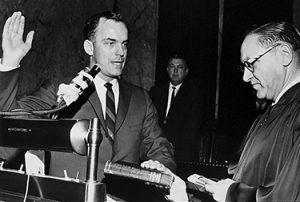

Evans is sworn in as governor for the first time in 1965. He was later named one of the top 10 governors of the 20th century in a University of Michigan study.

Evans’ plans did not always meet with success. Several times he proposed a state income tax to support equitable education. “It was apparent to me that public education would be permanently shortchanged without major reform of our regressive state tax system,” he said. But the Legislature repeatedly balked, and when a tax overhaul bill finally passed the Legislature and was sent on to voters as a constitutional amendment, it went down to resounding defeat.

His proposal for the creation of community health centers was largely ignored. He wanted highway funding removed from the pork barrel and located in a new state Department of Transportation, which would also give mass transit a higher profile, but the state didn’t make that change until long after he had departed the Governor’s Mansion. The idea of holding a constitutional convention, with an eye toward consolidating “a multi-headed executive branch,” fell on deaf ears.

Still, he enjoyed a high national profile as a future party leader. He was invited to give the keynote address at the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami and told the delegates that it was time to make America great again—by addressing the pressing problems caused by war, poverty, lack of equal opportunity and the barriers to free enterprise. The convention went on to anoint Richard Nixon as its presidential candidate.

“I’d rather go down swinging than survive as a chicken.”

Dan Evans

In 1969, Evans faced the state’s deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression. The Boeing Bust sent the jobless rate in Seattle soaring to nearly 16%, with about half those unemployed not entitled to any public financial support. Home repossessions rose eightfold. Evans secured extra federal assistance with the intervention of Senators Warren Magnuson and Henry M. Jackson. He also called for a series of state bond issues to jumpstart the economy through capital investments in waste disposal, water supply, recreation, health and social services, public transportation and community college. Every one of these was defeated in 1971, but undeterred, he offered them again the following year as part of his successful re-election campaign. Four of them were approved by the state’s voters, but the measure to improve public transportation was defeated.

Nancy Bell Evans with her husband, Dan, and children. (Photo courtesy of the Evans family)

Evans’ final term as governor included proposals for a state role in the creation of child-care centers for working families and a study of what the state could do to help people cope with the economic consequences of catastrophic illness. He urged lawmakers to focus on addressing problems of hunger, poverty, lack of medical care, support of the elderly, and civil rights. He said they had the opportunity “to make Washington the most progressive state in the nation.” But the Legislature, especially his ever-more-conservative Republican colleagues, had little interest in being progressive.

Evans, undaunted by setbacks, commented, “I’d rather go down swinging than survive as a chicken.”

As his party statewide and nationally shifted ever further to the right, he didn’t hesitate to raise his voice in opposition. “The genius of American political parties has been that they refuse to become ideological hobby horses,” he said. He wasn’t a fan of big government. Or small government. What he wanted was smart government.

See also: A conversation with Mr. Washington

In defense of his time as governor, often against his own party members, he noted that taxes in Washington had grown at a slower pace than the rest of the country and the welfare caseload was half of the national average. The critics were not mollified. The acronym RINO (Republican in name only) had not yet crept into common use, but the sentiment was there.

When the Republican National Convention in 1976 was set to meet, state party operatives, enthusiastic supporters of Ronald Reagan, denied Evans, who leaned toward Gerald Ford, a place in the state delegation, although he was the senior Republican governor in the nation.

When Evans left office in 1977, he was barraged with requests to serve on corporate boards and other high-level positions. He surprised some by accepting the offer to become the second president of The Evergreen State College. Evergreen, authorized in 1967, had pioneered an approach to education focused on portfolios rather than grades and attracted a student population that often marched to a different drummer, which raised the ire of some legislators and the incoming governor, Dixy Lee Ray. Still a startup, it was under-enrolled, which became the principal excuse for critics recommending its closure.

- Evans scaling down Evergreen’s clocktower. Photo courtesy Evergreen State College.

- Evans at the 1972 ceremony for the dedication of Evergreen’s recreation center. Photo courtesy Evergreen State College.

- On March 21, 1967, cabinet members joined Gov. Daniel Evans to sign legislation establishing The Evergreen State College. The school would open four years later, and Evans assumed the presidency in 1977. Photo courtesy Evergreen State College.

Evans bought the school enough time to raise its profile and attract laudatory comments from independent reviewers and graduates. He also created a sense of unity and mission among faculty and students. By 1980, the turnaround was complete, as Evergreen faced the new challenge of over enrollment.

But the Evergreen presidency was apparently insufficient to occupy all of Evans’ time. He accepted a position on a brand-new body, the Northwest Power Planning Council, which was charged with developing a plan for electric power in the region over the coming two decades. At its first meeting, he was elected chairman.

The council met with representatives of the major power companies, public and private, as well as experts on regional fisheries, wildlife and Native American rights. The council posed hard questions to the Army Corps of Engineers and considered a range of ideas to secure the region’s energy future at the lowest cost and least environmental impact.

Dan Evans with his father and fellow engineer Daniel L. (Les) Evans, ’17. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

Its most important conclusion was that the cheapest source of energy was conservation. This has become a cornerstone of the council’s planning. Indeed, the panel’s name is now the Northwest Power and Conservation Council.

When Sen. Jackson died suddenly in 1983, Evans received a call from his longtime colleague, Gov. John Spellman, asking him to fill the seat until a special election could be held. From the day he accepted the appointment, Evans knew he would run for a full term. He engaged in a two-month campaign for the seat against then-Rep. Mike Lowry. Evans was dismayed that the bulk of the campaign went into empty, often misleading ads and “time-constrained debates that squashed intelligent exchanges on complicated issues.” Evans won with over 55% of the vote, but he and Lowry became good friends after the election.

It’s safe to say that Evans’ time in the Senate was the least satisfying of his career. Although he was able to advance legislation expanding wilderness areas in Washington’s national parks and also gained protection for the Columbia Gorge, he was disappointed with the way the purported “world’s greatest deliberative body” conducted business. He described the congressional budget process as “convoluted duplicity.”

Evans with Richard Nixon. Photo courtesy of Dan Evans.

Ever the optimist/pragmatist, he worked with a group that proposed major shifts in government responsibility, turning many aid programs back to states while allowing them to use federal funds to expand job training and child-care services. “We spend so much time and money regulating and supervising the states instead of delivering services,” he said. Few legislators signed on to even explore those ideas. “It was apparent that a junior senator could not bring a proposal of this magnitude to fruition, and neither the president nor congressional leaders chose to lead.”

At the age of 63, Evans declined to run for re-election. He was interested in joining the administration of George H.W. Bush, particularly as Secretary of Interior, but he was reportedly deemed too “liberal and balanced” for the job.

Other doors were open. He and Lowry hatched a plan to advance their shared environmental concerns. They developed a way to save old-growth greenbelts, protect endangered habitat and build parks by creating the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Coalition as both a political lobby and administrator of matching funds.

In 1993, Lowry, who had just been elected governor, appointed Evans to the UW Board of Regents, where he served for 12 years. A Seattle Times reporter who observed him at the board meetings described him as “blunt and independent.” William P. Gerberding, UW president during much of Evans’ time on the board, commented, “He remains slightly larger than life.” The favor was returned: Evans described Gerberding as a “transformational” president, responsible for enhancing the university’s excellence, increasing faculty pay and expanding research.

Evans, who died September 20 at the age of 98, lived long enough to see his Republican Party morph into a very different entity, one that would expunge those with moderate beliefs and values in much the same way that he had urged expulsion of the John Birch Society. “Most Republican voters now share Trump’s principles, not the principles of Ronald Reagan or Dan Evans,” commented Chris Vance, former state Republican Party chairman.

Evans, optimistic to the end, continued to urge his fellow citizens to become civically active and to participate in the “generosity of voluntarism.” He remained convinced that “leadership comes from those with vision, wise planning and the ability to listen to others. People will give their votes to those leaders and that party who can best speak for their aspirations.”

Mike Flynn, longtime reporter and editor of the Puget Sound Business Journal, said it best. “He has always been a leader in what … is an unfortunately disappearing breed, those who view ideas on their merits rather than insisting that any new idea must be vetted based on where it fits ideologically. [He is] likely the most important political figure in Washington state’s history.”

Bob Roseth retired as director of UW News & Information in 2013 after nearly 30 years in the role. He helped found the UW’s Professional Staff Organization and served on the board of the League of Education Voters. Post-retirement, he has volunteered as a Washington state long-term care ombudsman. His first novel, “Ivy is a Weed,” is a mystery set at a large public university.