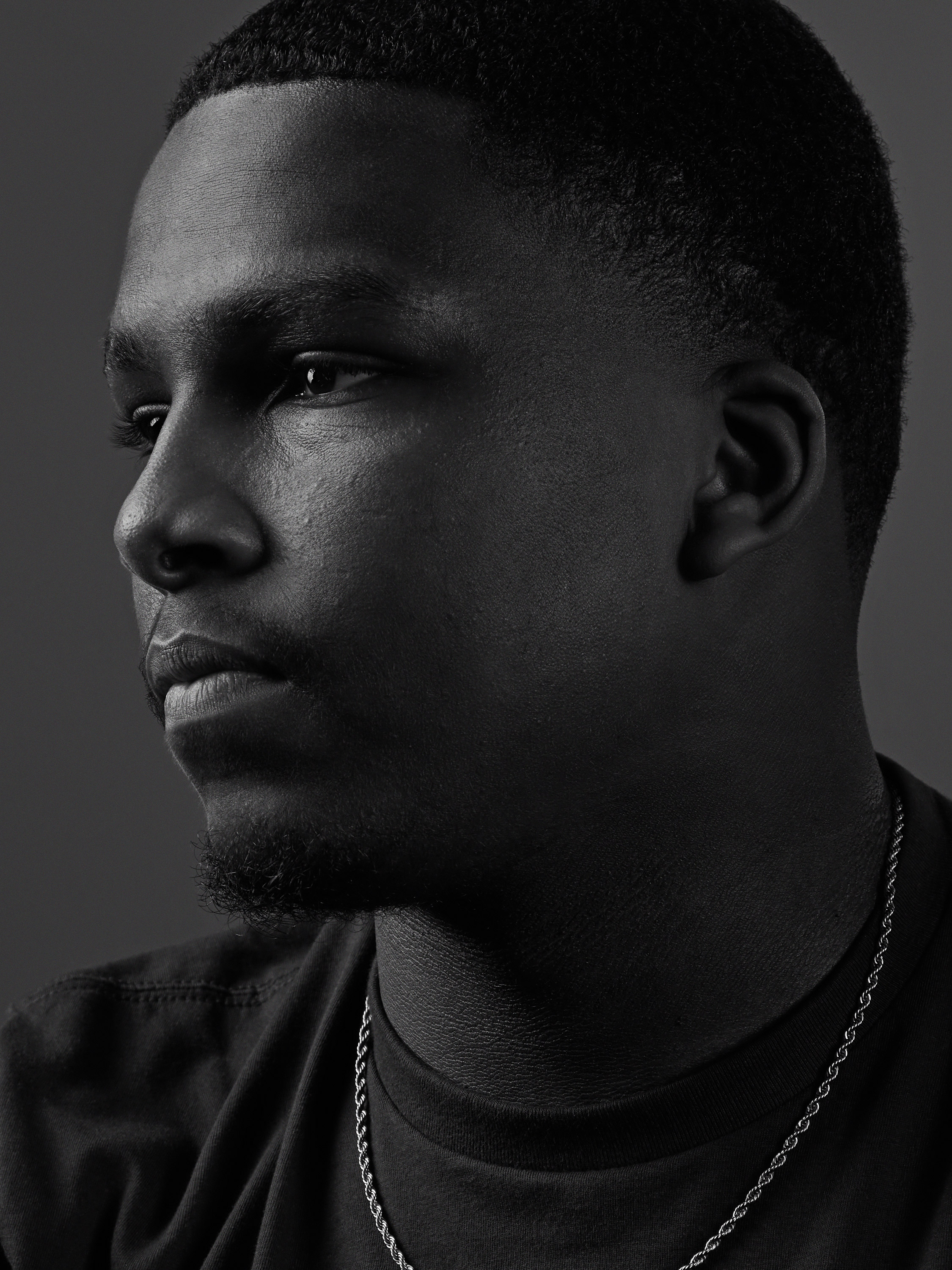

Black Voices: Justice should be our North Star Black Voices: Justice should be our North Star Black Voices: Justice should be our North Star

“We need an urgent shift in the climate and system stemmed in anti-racism, anti-colonialism, and any other form of discrimination,” says Claire Gwayi-Chore, a Ph.D. student in Global Health.

bY Claire Gwayi-Chore | Viewpoint Magazine

This is part of our “Black Voices” issue of Viewpoint Magazine. Go here to see the full package.

When the color of your skin is seen as a weapon, you will never be seen as unarmed.

When I read this quote from the Black Lives Matter movement, I knew I had to respond. It spoke to me in such a visceral way. Yet, weeks of quarantine and juggling teaching, learning and research—the typical unbalanced life of a graduate student—had me so stressed and exhausted, I couldn’t even think of what that “something” was. The University had shared so many resources and messages in regards to the pandemic, yet my Department of Global Health, the wider School of Public Health (SPH) and the greater University were silent about ongoing racial injustices. It was clear that students who identify as Black, Indigenous or a person of color (BIPOC) were not being prioritized, and I could no longer stay silent. So, at 7 a.m. on May 28, three days after George Floyd was killed by police, I opened my laptop and wrote an email to my department and school leadership stating: “Please check on your Black students, colleagues and friends. We are not OK.”

In that message, I emphasized the mental and emotional stress of performing as a Black student. It is already difficult enough navigating academia while Black. Imagine having to deal with all of that while dedicating your energy to anti-racism and diversity, equity and inclusion work on- and off-campus and trying to manage the impact of COVID-19 on your community—all while seeing on TV every day for months others who look like you being murdered.

I do not take all of the credit for catalyzing the school into action, but for many, that was a moment of awakening. I was suddenly pulled into meetings with my chair, dean and other leaders from across campus. I was invited to share my perspective with various advisory boards. I suddenly had access to the voices, policies and strategies that decide my success as a BIPOC student in terms of recruitment, matriculation and graduation. I learned how the academic system really works and what drives decision-making. However, that access came with a price.

First, I became the educator—teaching about the impacts of racism on BIPOC, defining what it means to be an ally vs. an advocate, explaining the harms of white supremacy, and disentangling the difference between intention and impact when moments of white fragility emerged. Second, I became the crusader—speaking up for other BIPOC students who feared retaliation or felt that their voice would not be heard. Hearing their stories of racial trauma experienced at the UW was angering yet bizarrely affirming. I felt deflated at hearing how the institution failed to protect them, yet saw myself in similar moments when I wondered whether I was irrational for feeling like a victim of a macro- or microaggression. Third, I became the laborer—developing and reviewing strategic documents, crafting public messaging, updating curricula and bylaws, and organizing meetings, all while protesting for my life to matter.

My personal currency of activism was quickly depleted. By July I was mentally and emotionally exhausted. I had to unlearn all of the productivity parables I thought were true and learn that rest, in itself, is a radical form of activism for people who identify as BIPOC. And so, I took a much-needed break to refill my activism “purse” and reframe the work that I am passionate about.

This is the message for the University, especially those who teach, advise and support students: You cannot rely on BIPOC students to do the work of labeling and disrupting racism. Working toward anti-racism is a collaborative effort and everyone must take part—especially those who benefit most from racism and white supremacy. We do not need acts of performative activism like one-off emails or panel discussions. We first need deep, introspective learning to understand the history and practice of racism and colonialism in higher education and research, followed by time to unlearn all of the resulting overt and covert violent practices against BIPOC educators and students. In turn, we must develop strategic, intersectional responses that aim to dismantle—not merely transform—the racist system we all live, work and learn under. In short, “the same systems responsible for our oppression cannot be responsible for our justice,” as Derecka Purnell of The Guardian wrote.

As a new academic year starts, and in the wake of a new wave of global protests for Black Lives Matter, the University must work harder to confront and dismantle racism. This effort requires urgency because as you wait, your BIPOC students continue to be stressed, harassed, injured and murdered. Speaking on behalf of students, we have to be able to keep our leadership, faculty and staff accountable and demand change without fear of repercussion. We need an urgent shift in the climate and system. It must be steeped in anti-racism, anti-colonialism and any other form of acting against discrimination that affects the safety and success of students, especially those of marginalized and underrepresented identities.

I hope that the UW aims to amplify the voices of student-activists like me who are committed to confronting and dismantling racism and thus, helping make the institution a better place.

Justice, not merely impact, should be our North Star.

Warning: Undefined array key "thumbnailoption" in /data/www/columns_wordpress/wp-content/themes/columns/vendor/Columns/MagazineGallery.php on line 179

Warning: Undefined array key "thumbnailoption" in /data/www/columns_wordpress/wp-content/themes/columns/vendor/Columns/MagazineGallery.php on line 179