Black Voices: What the UW has gotten right Black Voices: What the UW has gotten right Black Voices: What the UW has gotten right

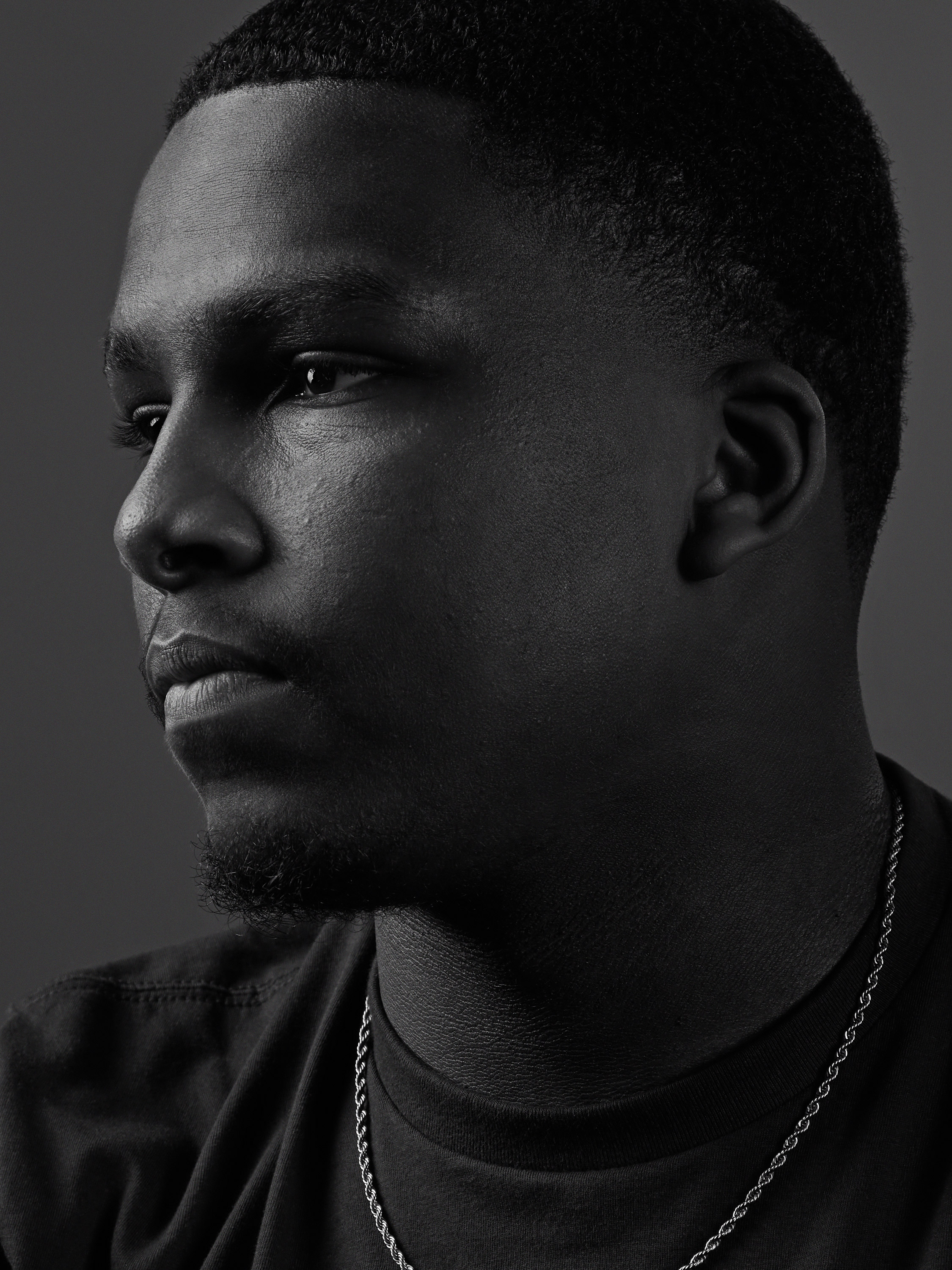

“It’s important to take stock of what we’ve accomplished so we can remember that our collective activism, past and present, isn’t in vain,” says LaShawnda Pittman, an assistant professor of American Ethnic Studies.

By LASHAWNDA PITTMAN | Viewpoint Magazine

This is part of our “Black Voices” issue of Viewpoint Magazine. Go here to see the full issue.

It’s important to point out what the UW has gotten right. We have a sundry of initiatives and institutes that bring attention to the plight and power of Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC). To name a few: the Relational Poverty Network, Urban@UW, the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology, the West Coast Poverty Center, the Center for Communication, Difference, and Equity, the Center for Child and Family Well-Being, and the Population Health Initiative. In 2015, we hired Ana Mari Cauce, the first Latina to serve as our college’s president. In 2019, Joy Williamson-Lott became the dean of UW’s Graduate School. These kinds of hires are important because they demonstrate that women of color, who experience the negative effects of gendered racism on their careers, can move into leadership roles at UW and in academia. It’s important to take stock of what we’ve accomplished so we can remember that our collective activism, past and present, isn’t in vain.

Still, our administration is overwhelmingly white and male. We have a way to go to make sure the leaders within the various departments and institutes look like the greater University community and reflect the diversity that exists in the larger society. In part, this will require improving the pipeline for faculty of color at UW, which is a structural issue and not one unique to our university. Reducing the racial disparities that faculty of color experience at every stage of tenure and promotion will involve making sure they have the resources they need to be productive. This includes research money and support on a par with their white colleagues (since we know that BIPOC experience racial disparities in receiving external funding), being thoughtful about requests for them to provide service without taking something away (for example, a reduction in teaching load and other service work) or adding something (such as research and teaching assistance, summer salary or research funds), and mentorship at every stage so that BIPOC faculty are exposed to and supported in pursuing leadership roles across campus.

The UW is well aware that it needs more BIPOC faculty. According to 2018 data from the Board of Regents Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Advisory Committee, 69% of professorial faculty are white, while 1.8% are Black. The University also needs to retain Black faculty by eliminating—not just reducing—pay disparities, addressing the high cost of living in Seattle and incorporating their invisible labor into their tenure and promotion assessments since we know that faculty of color engage in additional “race” work.

We have programs that promote the hiring, retention, and success of a diverse faculty. I can personally say I’ve experienced, and at times witnessed, the effectiveness of these programs. But there is still work to be done. The lack of diversity in Seattle combined with the lack of affordable housing makes it a difficult place for BIPOC faculty and students—especially graduate students—to thrive. Students and faculty are drawn to UW for the opportunities, but they need compelling reasons to stay. One of the most compelling is the chance to “have a life” here, being able to afford a home and build community. Some of this can be done with cluster hires for faculty, graduate student recruitment and a housing initiative.

These are structural issues and we need to stop framing them as individual ones. As a sociologist, I know that if enough people are consistently saying and experiencing the same thing, it indicates a pattern that must be addressed structurally. In other words, it shouldn’t be up to each BIPOC faculty or student to remedy these issues on their own since most are in no position to do so.

What can you—the alum, student, faculty member or employee—do? Faculty can create opportunities for students to learn about racism and advance racial justice in more creative and impactful ways, incorporating their activism, art and community involvement into assignments. They can help students build community connections and collaborations based on their unique interests and career/learning goals and they can provide service-learning opportunities. This is work that my colleagues and I do in American Ethnic Studies.

I see my students calling for educational experiences that allow them to think and operate in fresh and creative ways and provide them opportunities to give back and learn outside of campus. I was recently involved with faculty and BIPOC student leaders in the University’s first Abolitionist Institute. It was a transformative experience for faculty and students alike. We need more of this!

Our students, especially BIPOC student leaders, are already doing so much to advance racial justice. Student groups including the Black Student Union, UW BLM, the African Students Association, the Graduate Opportunities and Minority Achievement Program, the Latinx Student Union, the Pacific Islander Student Commission, the American Indian Student Commission, the Association of Black Business Students and the Black Law Students Association, fill critical gaps on campus and continue to make demands to address their unique needs. I also hope that alumni, faculty and the administration support their efforts to make all that the UW offers them more racially equitable, just and safe. After all, they are the future.

Warning: Undefined array key "thumbnailoption" in /data/www/columns_wordpress/wp-content/themes/columns/vendor/Columns/MagazineGallery.php on line 179

Warning: Undefined array key "thumbnailoption" in /data/www/columns_wordpress/wp-content/themes/columns/vendor/Columns/MagazineGallery.php on line 179