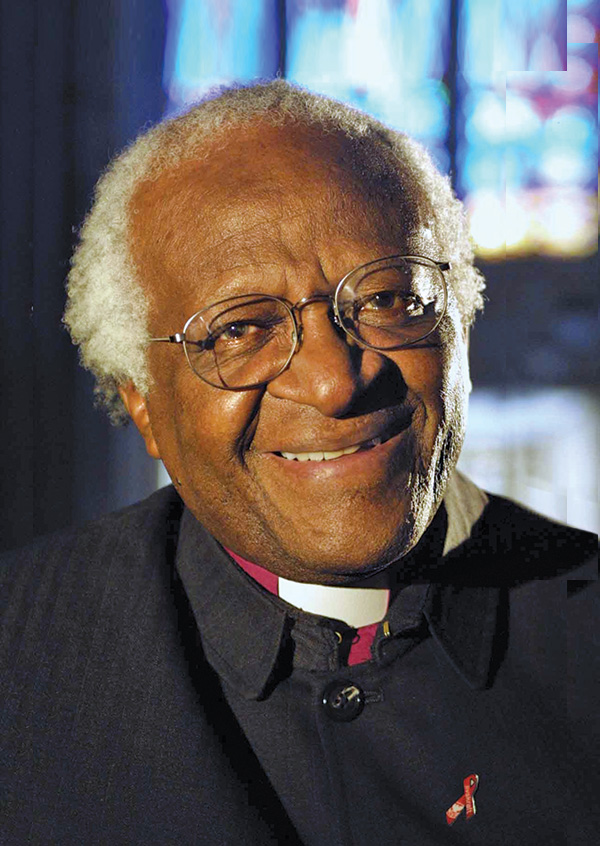

Remembering Desmond Tutu’s visit to the UW

20 years ago, the human rights leader delivered a message of hope to Seattle.

Twenty years ago, the human rights leader Desmond Mpilo Tutu delivered a message of hope to Seattle.

In May of 2002, Archbishop Desmond Tutu stepped on the stage at the UW in academic vestments while performers played joyous African music. Taking the lectern to receive an honorary doctorate, he flashed that smile familiar the world over: “Now you know, I’m a preacher … you’ve been warned.”

The crowd laughed, and for the next 30 minutes was enchanted by the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize winner’s magical speech. He confronted many of the world’s ills head-on, much the way he’d confront apartheid. His well-chosen words and gentle demeanor were weapons in his fight against oppression. “His disarming personality could in fact disarm people,” says Dr. Steve Gloyd, a School of Medicine professor involved in the event.

Tutu died in December at 90. For Gloyd and hundreds of others who took part in his Seattle visit, the occasion of his death caused them to reflect on the way the visionary touched their lives.

Seattle in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s was a hub of activity around African politics, and the UW was fertile ground for anti-apartheid work. “South Africa was inspiring the world, really, and that inspired the UW,” says Ed Taylor, ’94, now vice provost and dean of Undergraduate Academic Affairs. “There was student energy around inviting Desmond Tutu, there was faculty energy and our region and our nation had been paying attention to liberation in South Africa.”

After an 80-year hiatus, the Faculty Senate decided to revive the practice of bestowing of honorary doctoral degrees for Tutu. The occasion brought him to attend a forum on the health of the world’s children as well as a special academic convocation that included speeches, local dignitaries and musical performances. Tutu was dazzling. “I receive it on behalf of the millions and millions back home who are the real heroes and heroines of our struggle,” Tutu said of his Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. “For it is a truism: What is a leader without followers? And one becomes increasingly aware of just how much we really owe to those who erroneously are referred to as the ordinary people. In my theology, there are no ordinary people.”

Two decades later, that moment quickly comes to Taylor’s mind when he reflects on the day, he says. “He really believed at the time that the transformation to democracy was going to happen because of ordinary people,” he says. “He called them wounded healers who were going to nurture freedom.”

As a leader in the global health department, Gloyd spent one-on-one time with Tutu. “It lifted me up in a way that I hadn’t been for years,” Gloyd says.

The events of the day crystalized years of work in Africa for both Gloyd and Taylor. Gloyd worked in Mozambique in the 1970s assisting the implementation of the government’s ambitious universal health care plans. He remembers violence from the former Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and South Africa spilling across the border. After moving to Seattle, he was one of eight doctors arrested for demonstrating outside the South African consul’s house as part of a Seattle Coalition Against Apartheid protest in 1985. The protesters were offered a plea deal, but turned it down, he says, largely because it required them to promise not to get arrested again. Gloyd started his UW employment as a lecturer shortly after the trial. “I don’t think they knew about that at the time,” he says with a chuckle.

Taylor also spent significant time in Africa, beginning with his participation in Professor Jim Clowes’ Comparative History of Ideas program. UW students and faculty began visiting the country shortly after Nelson Mandela, who had been a political prisoner, was released in 1990. “So the South African citizens were just starting to vote and the nation was becoming liberated in some ways,” Taylor says. “That was my first connection. I was working with schools in South Africa, in Cape Town and in the Port Elizabeth communities.”

Tutu returned to Seattle in 2008 for an event to improve the lives of children. He and the Dalai Lama spoke together. “They talked about compassion,” Taylor says. “They talked about love. They talked about joy. And they shared this dynamic between the two of them that was just absolutely modeling joyfulness and compassion and playfulness.”

That second visit to Seattle came at a hopeful time. Legislated apartheid in South Africa had ended, the world was a more democratic place and the U.S. was on the verge of electing its first Black president.

“They both spoke to how important it is that we see the interconnectedness, and move away from divisions, whether that be divisions between race, gender, class divisions, even separateness around environmental justice,” Taylor says. “They were really bringing this interconnectedness theme as a way to address global issues. First and foremost, it starts with seeing the world through a lens of equal rights and compassion and justice. They saw that as hand in hand.”