The Kelly ECC at 50 The Kelly ECC at 50 The Kelly ECC at 50

Once a student activist’s dream, the Samuel E. Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center celebrates five decades as a space for diversity and inclusion.

By Hannelore Sudermann | Photos by Emile Pitre | March 2022

Credit should start with Eddie Walker. In 1966, the Cleveland High School honors graduate came to the UW and found it lacking. Of the University’s 32,000 students, only about 60 were Black, and there were hardly any faculty of color. Growing up in the Central District, he was accustomed to a multicultural community. While he encountered Chicano, Asian and American Indian students on campus, they just disappeared into the landscape. “It scared me,” he says.

Art, activism and culture were his priorities. Walker was raised on the Bible and the poetry of W.E.B. Du Bois, his mother’s favorite. In his 20s, he was studying the likes of Camus, Sartre, Che Guevara and Diego Rivera. He attended civil rights and Black student leadership rallies that mobilized students to engage in the social justice movement. He understood how important culture was in activating change, and as a founding member of the UW’s Black Student Union, he created a role for himself as “Minister of Arts and Culture.” “It was by self-definition,” he says with a laugh. He was longing for an art department or arts community to connect with. When the other BSU leaders asked him what he thought the UW needed, “I said, an ethnic cultural center, something multiethnic so the different cultures can be near each other and go to other people’s events,” he says.

“We needed a building. We needed a space to be together. And we needed a theater so the community could come out and join us,” says Walker. E.J. Brisker, at that time the president of the BSU, added to the vision a center where students could be tutored through their most difficult classes.

Cultural celebrations are the norm at the Kelly ECC. These folklorico dancers perform at a 2015 event hosted by MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán).

Walker’s vision was a space where Black, Hispanic, Asian, Pacific Islander and Native American students could meet and eat and party and dance together. Where they could teach each other and organize around social justice goals. Where they could make themselves at home. The BSU leaders handed the request to Samuel E. Kelly, the UW’s newly hired vice president for minority affairs. Kelly’s position had been created just a year earlier in response to student activism, particularly the BSU-led sit-in in the president’s office in 1968.

A former Army colonel and the UW’s first African American senior administrator, Kelly was the perfect champion for underrepresented students. “If Sam Kelly decided something needed to happen, he went after it,” says Emile Pitre, ’69, a student activist who ultimately served as director of the Instructional Center adjacent to the ECC, chemistry instructor and associate vice president in the Office of Minority Affairs and Diversity.

Heeding the call of student activists to hire more faculty of color and recruit more underrepresented minority students, President Charles Odegaard and the Board of Regents also approved the plan to build a student center with a multiethnic focus. They funded the project with $239,000 and hired Benjamin McAdoo Jr., ’46, to design the project. McAdoo, the first Black architect licensed in Washington, was also the first African American to have an architectural practice in the state. He was best known for his midcentury modern houses, but his building designs also included churches, a fire station and the Queen Anne public swimming pool.

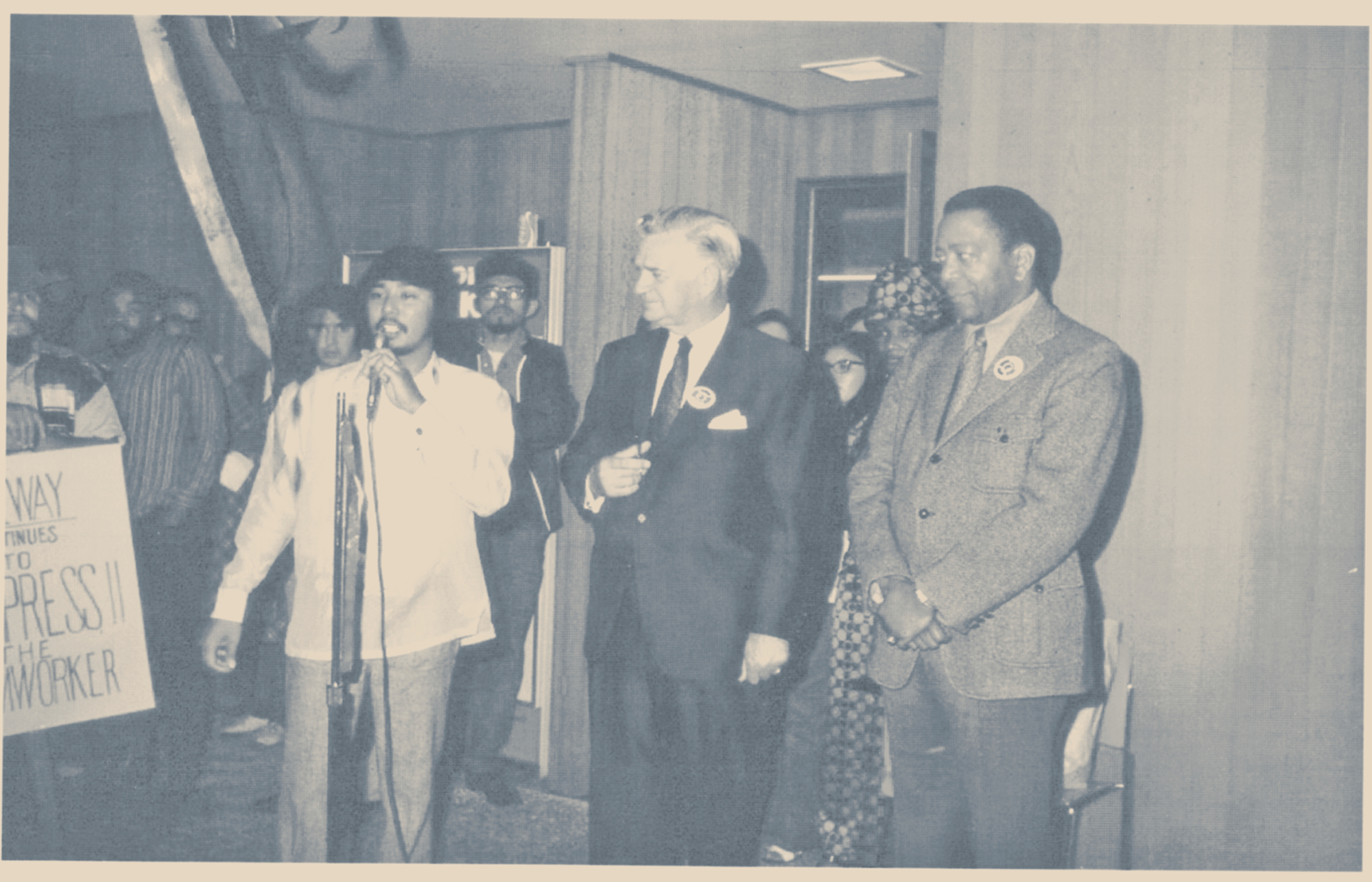

Roy Flores, the first director of the Ethnic Cultural Center, left, President Charles Odegaard and Vice President for Minority Affairs Samuel E. Kelly at the dedication of the original Ethnic Cultural Center in 1972.

For the site two blocks west of campus at the intersection of Brooklyn Avenue Northeast and Northeast 40th Street, McAdoo designed an understated, one-story wooden, modern-style structure. While the center had its grand opening in the spring of 1972, it was already welcoming students in 1971. Walker, who had been traveling, came home to find a fully realized Ethnic Cultural Center. “They did it!” he says. “I was in shock. It was too wild.”

The students wasted no time claiming the space. Emilio Aguayo, ’72, painted the first large mural on the Chicano Room wall. Today his work, “Somos Aztlan,” is one of the oldest preserved Chicano murals in the region. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, murals—on houses, schools and city buildings—were fast becoming a major element in the Chicano movement across the South and West. “I got the idea that art always helps a cause,” Aguayo said in a 2016 interview with the Seattle Civil Rights & Labor History Project.

Walker took on the next mural, “Bearers of Culture,” which features an African American woman with images of other Black women in her hair. “I wanted to celebrate Black women,” he says. “No one else was doing it. They were the ones who organized and got things done.” He didn’t ask anyone for permission to do the project. Walker bought his own paint, drew the outline freehand and painted it before anyone could stop him. Asian American students and Native American students later followed with their own murals in the ECC.

“Even in its first few years, the center was a hotbed of activity,” says Sharon Maeda, ’68, who became the second UW director of the ECC in 1973. Every week, members from MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán), the American Indian Student Association, the Asian Student Coalition and the BSU came for their meetings. Students also used the space for major events and celebrations, to plan protests and paint picket signs, and often just to hang out, study or make a meal. “That kitchenette was very important,” says Maeda. “It’s not like now when you can buy all kinds of food on the Ave.” For many students, food was a key connection to a sometimes-distant home. “Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, never mind that the University was shut down, they needed the kitchen,” she says. She recalls one student who would bring boxes of flour tortillas from Yakima to sell to his classmates. Another would sometimes turn up with coolers of salmon from his reservation, selling the fish to defray his college expenses.

From the start, the center had its own social justice library, where students could access history and literature. The authors included Angela Davis, Zora Neale Hurston and Octavio Paz.

While student funds helped pay for the construction and maintenance of the building, there wasn’t any support for programming. So, Maeda and other staff started writing grants to fund theater productions and cultural events. Students invited speakers like Stokely Carmichael and Julian Bond, both leaders in the Black Power movement. They also brought in playwright and filmmaker Luis Valdez and mounted a production of “I Am Joaquín,” a work centered in the Chicano movement.

“That’s one of the beautiful things about living in the Pacific Northwest. We’re so diverse here, and this provides a facility where people can learn about each other.”

Alex Rolluda, '85

Every week brought new activities and new uses. In 1983, the National Coalition to Support Indian Treaties used the center for a forum on highly radioactive nuclear waste—the dumping of which affected Indian reservations and communities. A week later, Chang Wen-Lung performed Chinese classical music in the theater. In 1992, activist Helen Zia, then editor of Ms. magazine, came to visit with students. The performance space known as the Ethnic Cultural Theater housed larger student meetings, as well as performances of works by multicultural playwrights by The Groupe Theatre.

Alex Rolluda, ’85, who had spent much of his childhood in the Philippines, came to the UW in the 1980s to study architecture. As an undergraduate, he rarely ventured from the architecture building. “But I was approached by some friends who asked me to join them at a party at the ECC,” he says. “There I found people of similar backgrounds just hanging out.” When you’re in a UW class with 250 students, it can seem overwhelming, he says. Students like him needed to decompress and see people from their own cultures. As an architecture student, he understood the value of the center not looking like the rest of the UW. “It was nice. You could just get away from all the collegiate Gothic and, being about a block away, you could feel a little detached from the main campus.”

Two decades later, the UW hired Rolluda’s firm to rebuild the center to serve a growing population of students. More than 70 student organizations were using the center and the need had far outgrown the original facility. Also, McAdoo’s original wood building, somewhat of a temporary structure, had deteriorated over nearly 40 years of heavy use. Rolluda’s partner, Sam Cameron, ’73, brought his own perspective as an African American student who had to transition from a small town to a big-city campus. So did Sam McPhetres, ’99, ’07, who grew up in the Northern Marianas. “Between us, we had the decades covered,” Rolluda says.

The architects worked closely with students and alumni to understand their priorities. A kitchen space was a must. So was saving the murals. “And socialization was very important,” Rolluda says. “The students wanted to be able to look across the hall to see what’s going on in different parts of the building. They didn’t want people hiding behind walls and doors, and they wanted to share their cultures on the walls and through the doors.” The design team was inspired by the idea of a vibrant, open marketplace.

The new, $15.5 million, three-story structure of wood, stone and concrete references some of the details of McAdoo’s original design. It is modern, and intentionally not collegiate Gothic. It has two major atrium spaces, a performance studio, with wide staircases and hallways where people can easily stop for conversations. When the students arrive, usually after their morning classes, the building really comes to life.

“We asked students what they wanted their experience to be from the time they stepped in the front door,” says Rolluda. “One of the first comments was, ‘I smell food.’ They wanted the smells to go up to the third floor and attract people down to share.” They also wanted it filled with art and dance, a place to do taekwondo, tai chi or stick dancing from the Philippines. “That’s one of the beautiful things about living in the Pacific Northwest,” says Rolluda. “We’re so diverse here, and this provides a facility where people can learn about each other.”

When Maeda attended the grand opening of the new building in 2012, “I was awestruck. It was beautiful,” she says. Eddie Walker came in at the same time and looked up to see his mural hanging above in the main atrium. “Tears just ran down his face,” Maeda says. “He was blown away.”

More than a space to organize for social justice or socialize, the center has remained rooted as a sanctuary. In 2016, the year #BlackLivesMatter became an international movement, the ECC was the site of a teach-in, bringing together the University community and alumni. In 2017, when the federal government announced it would terminate the DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) program, many students who were either undocumented or who had undocumented family members were in distress. The ECC, which already had the Leadership Without Borders program in place to help undocumented students develop as leaders, became a resource for legal advice and counseling.

A few years ago, Yuhaniz Aly first stepped foot in the ECC as a high schooler to attend an event. “It was my first time in any UW building,” she says. She found it again as a high school senior, touring campus on a Purple & Gold recruitment visit. “I was excited about being a Husky,” she says, “and I asked if they hired students.” That led her to working at the center for the past four years. Before COVID-19, she would see hundreds of students come through each week. “It was my first community at the UW,” she says. “I met some of my closest friends there.” Because there wasn’t a club representing her Cham culture—a population of Muslim communities from Vietnam and Cambodia—she was invited to join other student clubs. “The upperclassmen that I met, they were just so passionate in their identities.” Then, with an ECC adviser’s encouragement, she revived the Cham Student Association.

Aly encouraged her classmates to explore the ECC. Magdalene Tran, one of her friends from high school, came for the center’s block party at the start of her sophomore year and found a place for herself, particularly in the space of civic engagement. As a staff member of the ECC, she has helped coordinate viewing parties and local election events where students review voters guides together.

While it opens in the morning, the center typically comes to life after lunch, Tran says. Students come in to study or watch music videos on YouTube. A dance or movement class may be taking place in the studio, and the Chinese Student Association might be making dumplings. “It is always so lively in the building, you can hear student voices coming from all the floors,” says Tran. “For me, it’s a home away from home. It’s a space where I have developed, not just as a student, but as a person. It’s where I hear the most about activism on campus and where I can create social change.”