Nobel Prizes, Pulitzer Prizes, MacArthur Foundation “genius” grants, Lasker Awards, elections to prestigious national academies … faculty, staff and alumni of the UW have won ’em all. But there’s a less-well-known organization that for the past six decades has honored some of the most accomplished people in a most impressive range of fields: The Academy of Achievement. And it’s no surprise that three people with strong connections to the UW are among them.

From Maya Linn to Archbishop Tutu to Sally Ride to Arnold Palmer, members from the arts, business, science, public service and sports communities make up an incredibly diverse collection of visionaries and overachievers whose impact has been immeasurable. One example is Linda Buck, ’75, a neurobiologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center who received the 2004 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology for her pioneering work on the mechanism of smell.

Linda Buck. Photo by Henrik Montgomery.

Neurobiologist, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

2004 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology

Inducted into the Academy of Achievement in 2005

Funny, Linda Buck didn’t start out on the path to scientific stardom. As a UW student during the crazy, early 1970s, the Seattle native was really interested in psychology. Her goal then was to become a psychotherapist. That lasted until she took her first UW undergraduate course in immunology. She loved it so much that she switched her focus to biology. (Her UW bachelor’s degree was in microbiology.) After earning a Ph.D. in immunology from the University of Texas at Dallas, she went on to work in research positions at Columbia University and Harvard University before joining the UW in 2002. In addition to her role at Fred Hutch, she is an affiliate professor of physiology and biophysics at the UW.

Her work on the mysteries of the nose started in 1988, when she decided to map the olfactory process at the molecular level. The daughter of an electrical engineer-slash-inventor father and mother who loved to solve puzzles, Buck believes she got her answer-seeking chops and curiosity from her parents. “One of the things I love about doing science,” she said, “it’s really puzzle solving.”

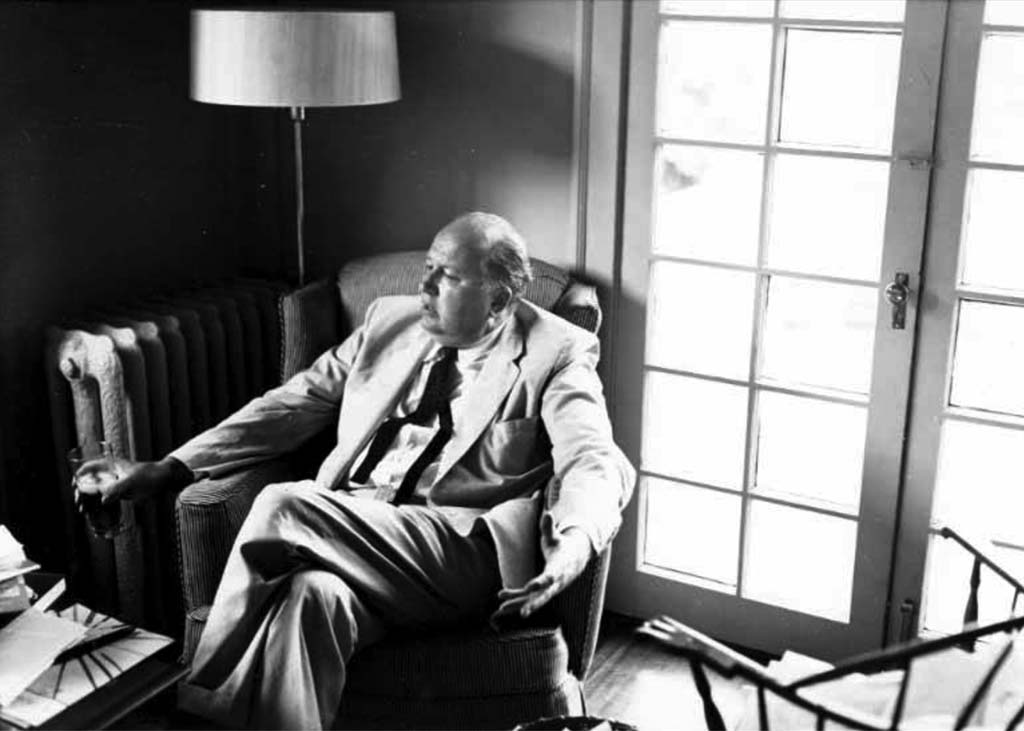

Theodore Roethke. Photo courtesy of UW Libraries special collections.

English professor at the UW, 1947-1963

Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, 1954

One of America’s greatest poets graced the UW campus for 16 years following World War II, evidenced by the Pulitzer Prize he received for his 1953, work “The Waking: Poems 1933-1953,” and National Book Awards for his 1957 book “Words for the Wind” and “The Far Field,” which was published in 1964.

He had quite a noteworthy career for someone who had a happy childhood growing up in Michigan despite being a thin and sickly child. He particularly enjoyed helping his father in the family greenhouses and a local game reserve that his family oversaw. In a 1953 interview with the BBC he told interviewer Allan Seager that “I had several worlds to live in, which I felt were mine. One favorite place was a game sanctuary where herons always nested.” It was no surprise that his childhood experiences and love for nature had a huge impact on his poetry.

After teaching at several East Coast institutions, he came to the UW in 1947, where his writing continued to garner acclaim as he pushed his students to develop innovative ideas. He tragically died in 1963 when he suffered a fatal occlusion while visiting the Bloedel Estate on Bainbridge Island.

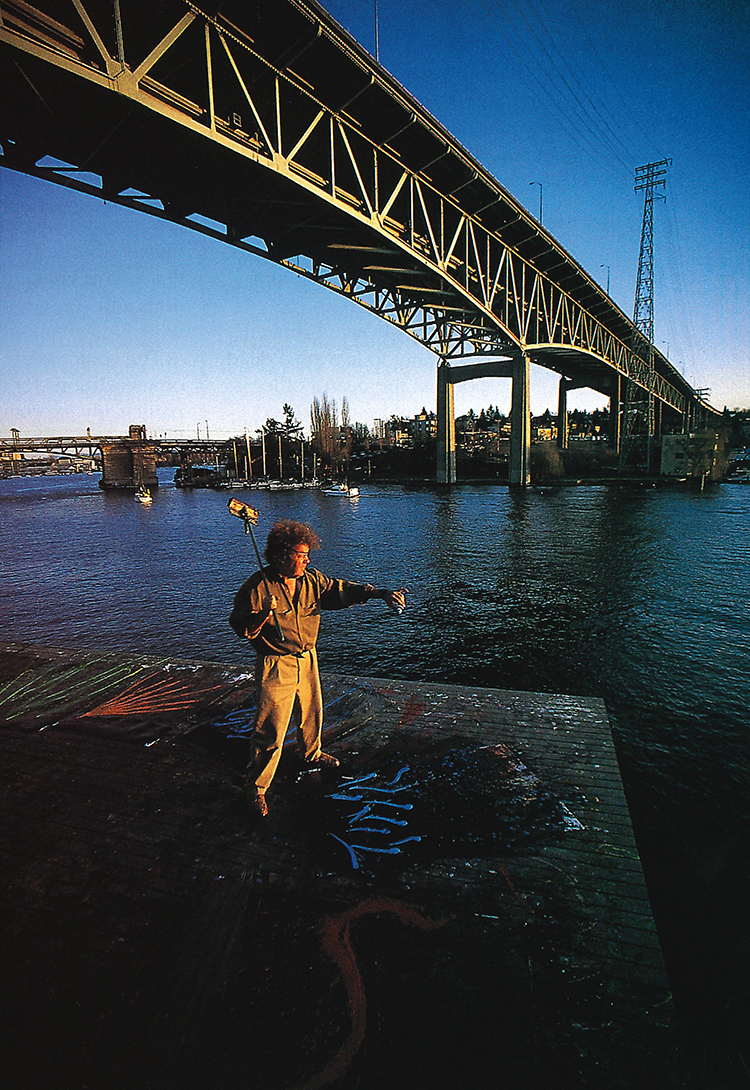

Dale Chihuly. Photo by Russell Johnson.

No one transformed glass into an art form the way Tacoma native Dale Chihuly did. Survivor of a terrible childhood tragedy when his brother George and his dad died within a year of each other, Chihuly attended the UW in the 1960s and earned a B.F.A. from the School of Art + Art History + Design.

After earning a graduate degree from the University of Wisconsin, he went on to create an entirely new field of art, turning blown glass into stunningly colorful and wildly imaginative designs that were as enormous in size as they were on the impact they left on their viewers. The inspiration was studying weaving with UW professor Doris Brockway, when he started to include pieces of glass into his textiles. That led him to study glass blowing a few years later.

Chihuly’s path to stardom – he’s been called one of the most important artists of the 21st century by Smithsonian Museum leaders, no less – took an unusual path. He worked in a meatpacking plant and as a commercial fisherman to save money for school. He also designed furniture. His art glass is on display in more than 200 museums worldwide.