9.11.01:

I was there

9.11.01: I was there

9.11.01: I was there

Two alumni who escaped the horror of Ground Zero bravely share their stories of trauma and hope.

By Perry Nagle and Annabel Quintero | September 2021

> Skip to “Step Step Jump” by Annabel Quintero.

Perry Nagle, ’88, holds bachelor’s degrees in art history and philosophy from the UW and a law degree from Cornell. He is a senior adviser for Forest Carbon, a private developer of carbon credit forestry projects in Indonesia, and a published author. “Into the Ash” is based on his experience at Ground Zero on Sept. 11.

Into the Ash

I’m on my hands and knees staring at the marble lobby floor of One Liberty Plaza. The World Trade Center is collapsing. The thundering gets louder and louder, driving into my head, each level sandwiching onto the next, in a cascading rage of destruction. The marble floor heaves under my hands. The glass lobby creaks as if preparing to implode. I’m a tiny blade of grass in a typhoon. A grain of sand in a tsunami.

My apartment was 400 yards from the World Trade Center. An hour ago, on a crisp autumn day with a bright blue sky, the South Tower had fallen. I wrapped a T-shirt around my face and ran for Ground Zero.

John Street, where I lived, was a hazy dim corridor smelling of burned electrical wiring, silent except for alarms deep inside buildings. The ash was 2 inches deep and felt soft. Halfway to the site, chunks of concrete littered the street, covered in thick ash like the surface of Mars. Up ahead, fires rumbled behind a wall of black smoke, churning and flashing white-hot flames.

Perry Nagle

At Broadway, I turned south, zigzagging as I jumped over debris. Suddenly an explosion ripped the sky. Black smoke billowed above me. More thundering explosions came. I ran for a revolving door at the back of One Liberty Plaza and fell to my hands and knees in a marble-floored lobby.

Time has slowed. The destruction seems far away. I stare at my reflection in the shiny floor. The black and silver marble is cool and smooth and slippery with ash. The shaking begins to subside. But the light is fading as smoke and ash engulf the building.

“Hold on,” says a man’s voice in the dark. Emergency lights activate. I’m in the glass lobby with four other people. A tall businessman in a dark gray suit, a guy in jeans and a red polo shirt, a building manager in his green work jacket, and a short-haired woman in a yellow parka who’s lying on the floor in a ball with her eyes closed and her hands over her ears.

The windows are black with inky thick soot. The businessman is standing with his hand on the glass like he’s trying to figure out how this is happening. Wondering, like we all are, how to run away if we can’t see or breathe?

The guy in the red polo shirt suddenly bolts for the door, trying to push it open as his shoes slip on the ash.

“No!” yells the businessman.

We grab him and he screams, thrashing as we topple backward onto the floor. The businessman finally gets him in a headlock and he begins to calm down. Resignation eases into his eyes. There is nowhere to go.

“You have to wait and the air will clear,” says the building manager.

After 20 minutes, the air outside turns from black to dark gray. Everyone wraps shirts around their faces and prepares to leave.

“There are huge fires along Church Street if you go north,” I tell them.

“Are you coming?” asks the businessman.

“I’m not,” I reply, “but I live nearby.”

The empty lobby looks dirty. There are coffee cups and pieces of discarded clothing in the corners, including a blue high-heeled shoe, and the shiny marble floor is dusted with ash and grit.

I exit to the south and see a police car right in front of the lobby with its blue and white lights flashing, thank God.

“Hello!” I yell from the door, but I can’t be heard because there’s about 6 inches of ash covering the whole car. The air is still thick with smoke and ash.

“Hello!” I yell again, approaching the car and knocking lightly on the side window, where ash falls away. “Hello?”

I lift the door handle and it’s unlocked. “Excuse me … hello?” I open the door slightly as ash sprinkles down onto the empty black leather passenger seat. The radio crackles and the engine is running. “Hello?”

There’s a cup of coffee in the cup holder, a clipboard on the driver’s seat, and a sweater lying across the center console, but no police officers. Two more police cars are empty, too, with their lights on and engines running.

Nearby I can see a huge fire truck with its front doors open and emergency lights flashing from under the ash. The hoses are unwound and most of the tanks and other gear are gone. But there’s something wrong with the truck. The front and back ends tilt upward at a strange angle. Approaching, I see a huge block of concrete has smashed the middle. A pair of gloves lie on the passenger seat and a radio handset dangles out the door.

“Are you OK?” I ask. “Do you know you’re bleeding?” He slowly looks down at his blood-caked shirt and then holds out his arms to examine them. “It’s not my blood,” he says in a rough voice. “I’m a paramedic.”

Returning to One Liberty Plaza, I navigate around to Church Street facing the site, which is covered in rubble. In front of me, what looks like the entire top of one of the towers is lying on its side, mostly exposed I-beams with some concrete floors still attached. Around it, rows of jagged stainless-steel columns point upward, which I think was the façade of the towers. Debris crashes to the ground from time to time but I’m protected by the building’s overhang. Farther up the street, black smoke belches and swirls and I can hear the low roar of fires. The sky is still obscured by a mixture of smoke and ash.

Behind me is what’s left of a Brooks Brothers store where I used to shop. The windows are smashed in and mannequins are strewn around. One reaches up toward an elegant wood display table with stacks of white button-down collared business shirts covered in a thick layer of ash.

Exiting the store, I find a man on his hands and knees coughing. He must have crawled in from the debris field outside.

“Hey are you OK?” I ask, kneeling beside him. He’s clenching his eyes shut and his entire face is white with ash, with tear streaks running down his cheeks.

“You’re bleeding,” I say, noticing his shirt, but he can’t seem to hear me. “Do you know you’re bleeding?”

I decide to go for help at the fire station that I remember is on the south side of the towers. But there’s more smoke in this area and my eyes are burning. I can’t see anything and have to turn back.

The bleeding guy has moved. He’s leaning against the wall with his eyes closed and there’s a trail in the ash where he dragged himself. Thank God, he’s still breathing.

“Hey, how are you doing?” I ask, kneeling again. He looks at me through narrowed bloodshot eyes.

“Are you OK?” I ask. “Do you know you’re bleeding?”

He slowly looks down at his blood-caked shirt and then holds out his arms to examine them.

“It’s not my blood,” he says in a rough voice. “I’m a paramedic.”

He closes his eyes and tilts his head back. A piece of debris crashes down across the street and he opens his eyes again.

“We had a whole team right here,” he says, turning his head to look at Church Street, which is completely buried. “Had everyone lined up. I came over to get something from my bag and everything came down.” He stares at Church Street. “I think that’s my ambulance,” he finally says, nodding at a bulge about 30 yards away.

We look at Church Street for a long time. Then I sit down and put my head back against the wall. It’s been a long morning.

The screech of metal scraping metal has me back on my feet.

“HEY, WHAT ARE YOU DOING?” I yell. There’s a guy across the street. He’s climbing on the pile and pulling on pieces of debris like he’s trying to find a way in.

“HEEEEEYYY!!” I yell again. “WHAT ARE YOU DOING!”

“Take it easy,” says the paramedic.

“He’s right out in the open,” I say. “He’s going to get killed.”

“He’s in shock,” says the paramedic. “He doesn’t know what he’s doing. You need to calm down. There’s nothing we can do for him right now. You’re in shock, too.”

A chunk of concrete smashes into the pile next to the guy and I instinctively turn away. But when I turn back, he’s clawing his way across the debris again.

Bright sunlight suddenly illuminates the pile in front of us and we look up at a small blue opening in the sky, which is gone in a moment when the smoke swirls again. I sit down next to the paramedic, put my head back against the wall, and close my eyes.

I’m awakened by the voice of a firefighter, who’s kneeling in front of the paramedic.

“Where is your team?” he says, but the paramedic isn’t responding. “Do you know where your team is?”

“He said he had a team on Church Street,” I say, nodding at the rubble.

“OK, we’re gonna get him outta here,” says the firefighter. “If you’re OK, you go talk to the captain over there,” he adds, pointing toward the fire station that’s now visible across the pile.

The fire department captain is standing in front of what’s left of Station 10 with several other firefighters. As I approach, he looks at me and frowns.

“What are you doing here?” he asks.

“I’m just trying to help,” I reply. “I got here when the second tower fell.”

“Have you seen anyone else?” he asks.

“There’s a paramedic over there with a firefighter helping him,” I reply, pointing, “and there were some people in that lobby but they’re gone.”

“That’s it?” he asks.

“That’s it,” I reply. “You’re the first guys I’ve seen down here.”

The captain shakes his head and scans the smoldering pile in front of us. “Get him a jacket,” he says to one of the firefighters. “And keep an eye on him.”

The jacket is heavy and reaches almost to my knees. It has large metal buckles in the front. I join three firefighters who are picking their way along Church Street.

“How come there aren’t more firefighters here?” I ask one of the guys.

“We aren’t the first wave,” he says. “We had to mobilize. Everyone who got the first call already came. We’re from New Jersey.”

Eventually more firefighters arrive. A fire truck is guided into place in front of One Liberty Plaza and men start unwinding long hoses and dragging them toward the pile. It’s time for me to go.

The fire department captain is still standing in front of Station 10, holding a radio handset.

“I think I’m going to go home,” I say.

“That’s probably a good idea,” he replies.

“Are you from Station 10?” I ask.

“We can’t find 10,” he says, shaking his head. “Hang the jacket in the engine bay.”

There’s a row of hooks along the wall in the empty engine bay. Rubble has spilled in from the doorway and is scattered across the shiny concrete floor. I hang up the jacket and turn to leave. The captain is back on the radio. “10 please respond,” he says. “13 please respond. Ladder 4 please respond. Do I have anyone out there?”

Two blocks from the site there is nobody. Just my muffled footsteps in the ash, silently tracking my way home through the hollow unfilled space of this busiest city on earth, now empty and quiet like an alien world.

Annabel Quintero, ’97, ’17, is the Seattle-born daughter of Ecuadorian immigrants and a survivor of Sept. 11. Her best-selling book “Step Step Jump” is a story of hope dedicated to helping others transform trauma to triumph. She holds a B.A. in political science and an M.Ed. from the UW.

Step Step Jump

The tower seemed to groan, twisting and swapping, shifting the world all around me. I was confused. I was terrified and unprepared. But I listened to the voice inside of me that spoke.

I said out loud, “OK, Annabel. You have to try. Try to get out of the building, even if you have to die trying.” And then I ran.

The floor was a jagged landscape, uneven and unpredictable. The building rolled, throwing me left and right. Each unforgiving step forward was a Herculean effort, my feet falling too far or catching the ground too quickly. My knees buckled, my arms knocking into walls that shouldn’t have been so close and grasping emptily. I twisted the handle and opened the door, slowly at first, preparing myself for more horror to erupt on the other side…

Annabel Quintero

I gripped the railing, focusing on coordinating my feet with the steps, my hands with the slope of the stairs. From the landing, I jumped down the steps, landing on my left foot in the middle of the flight. Grabbing the railing tightly but briefly, I sprang off, landing with my right foot on the landing this time. I took a second step, then again—step step jump. One more flight, one more landing, one more floor. Step step jump.

Yet, just like with all questions, as I stirred and tried to find meaning, I found mostly half-truths. My life, my memories, and everything I had ever read or learned about history, politics, and culture just poured out of me, gushing like a waterfall.

I loved my country, but I often felt ashamed of our collective history. In a way, I sympathized, not with what the men flying the planes had done, but with the broken hearts they must have been carrying inside of them their whole lives. To have lived a life of marginalization, oppression, and compromised futures is to have lived a half-life.

I grappled with why some societies were pitted against each other, the atrocities of the acts of governments, and the hatred that can bloom within a soul and transform planes into bombs. There is no separating the acts of our government from the acts of our own.

But they stole more than that, ruined more than that. The structures themselves had fallen, revealing a vulnerability our city and nation didn’t know or believe existed. Our financial structure had stalled, choking on the ash that caked the streets.

Conquer. The word rang through my mind so clearly and resonated deep within me. It was an active word, one rooted in fear, one felt by so many of my ancestors before me as their homes and lives were laid to ruin by those who felt they should live, worship, and behave differently. I felt their fear. I knew their pain.

That is what it felt like, that our rule was being usurped, that we were being overtaken, just like so many others had throughout all of history and modern mankind. I remembered, all at once. I remembered how my Indigenous ancestors had been slain by the Spanish in the name of expansion. I could feel my memory of reading that my Native American and African ancestors had been forced out of their homes and into chains by the white side of the world and my family tree.

It was a generational ache that bloomed in my chest, a deep-seated trauma I’d inherited in my genetic code—one snippet of helix reserved for the map of my eyes, which shone bright like my father’s. One was for my curly brown hair, which looked just like my mom’s. Another section held the memory of suffering, the dots and dashes of trauma from long ago.

It came in waves, invaded my body in gulps and gasps, overwhelming and underscoring every breath. I felt history wash over me in ripples, like a tide, feelings of ancestral pain overlaid with acute trauma. I had been that close to it. I was on the front of this attack, at the center of this newly minted Wall Street war. Fear enveloped me, and with my head in my hands, flashes of ancestral memory, of the back story of terrorism in this country, flitted across my mind.

When death comes to you, you listen. When you stare finality in the face, it’s your duty to pay attention to what is reflected back at you.

When death comes to you, you listen. When you stare finality in the face, it’s your duty to pay attention to what is reflected back at you. But mine was a collection of past experiences displayed, and a sensory journey, an exploration of my physical and spiritual selves. In many ways, it was an awakening…

The drumbeat had dispersed into a full-body thrum. I had never felt so aware of my life, so alive in my skin. I rested my hands lightly on the pew before me, and with my eyes closed, could feel the rivers within me. I was of currents, the flow of my blood a powerful force within me that I had never, ever felt before. But it wasn’t just the current of my blood, I realized, though that alone was a marvel. It was like pulling back the curtain of creation to see the elements that made us whole and human. It was energy. It was light. It was life itself. And it was all thanks to God.

Yes, fire had the capacity to destroy, but it also had the capacity to heal. Though there was so much I did not understand, I felt my heart open. Mother Earth was holding me in her womb, and my ego was dying off again; it was leaving my body there in that lodge … the sweat lodge was a catalyst, a cauterizer searing and sealing my wounds, sizzling the torn parts of myself back together again.

Each and every day since the towers fell, I feel its weight in my world. The pressure to make every day count, the guilt I felt in surviving but not yet having learned to thrive, the self-imposed silence I suffered through. To speak of that day in any way other than a whisper or a prayer seemed like an injustice to all of those we lost.

I had just begun the midlife search for more, the halfway point of reckoning that seems to happen to so many. I found myself looking for ways to add more meaning to my life, to deepen my purpose, and rekindle my journey toward growth.

I stood on stage in front of hundreds of people and said these words out loud: My name is Annabel Quintero and I am a September 11th survivor.

I asked the audience: “How many of you have an untold story? How long have you been silent?” That experience changed me. Instead of running away from tragedy—step, step, jump—I knew it was time to run toward my future with the same measure of force, energy, and speed.

Writing this book has evolved my healing, like medicine heals the body. We never truly know how much silence traps us and our true message, and our light is never truly experienced for all to see and feel. Just like in the ways we learn about ourselves, understand patterns and take new action to grow, that too is how we will evolve our society and this world. We are not separate from our history. It is as beautiful as it is painful. To know it and acknowledge it informs our collective patterns, so we can understand how we got to this present moment. When we understand structures and old mindsets then we can co-create a new systemic response and contribute to our collective consciousness and wellness.

My story is one of hope with thoughts and lessons that provoke us to heal: When you ask God or your higher consciousness a question, believe what comes up. And since you asked, heed the answer even if you are filled with fright.

In a crisis, if you don’t know what to do, stop and breathe. Connecting with the sacred through your breath can save your life, or at the very least, give you data to make the next best decision.

There are all kinds of traumas and healing is cyclical.

Humans create ideas and babies, everything else is given to us by Mother Earth. You can be faithful and still tease out what is not loving from your faith. Your intuition is your superpower.

If you hit rock bottom, when all the normalcy of your life is gone and you only have the shell of your skin: you are both enough and everything at the same time. Remind yourself, “I am a Soul experiencing life in this vessel.” Your spirit is more powerful than any condition or circumstance.

Your mind is powerful, when emotional overwhelm comes up, distract it by serving others. Being knowledgeable is not the same as being wise, let your wisdom be your wealth.

Your personal growth and healing contribute to the collective experience and consciousness. The mind can trap you or set you free, go higher in your consciousness beyond your five senses and see how everything begins to change.

Your enemy might just be you. You may not know what your silence is condoning, nor that your ignorance might be colluding with the problem.

That God is much more integrated within us than we allow ourselves to experience, that we are not separate from God, just like we are not separate from our government or our history. We are the church, we are the friend, we are the enemy, and we will be the ancestors.

Your story and how you give it voice can accelerate someone else’s healing.

My hope in sharing this story is that you begin to compassionately do your inner work.

I hope I have done my ancestors justice in sharing their history. I hope I have helped to shed light on the generational trauma that too often goes unspoken and unacknowledged.

I create safe spaces for leaders to examine, understand, and embrace their whole selves. As a cultural broker, I am committed to redefining cultural wellness and to help us discover how we define both culture and wellness.

My name is Annabel Quintero and I am a September 11th survivor. But I am so much more than that. I am an evolutionary monument to the fallen. I am a friend to the crows and a believer of saints. I am a city girl who is at home in the stillness of the trees. I am a child of the earth and a lover of life. We are far stronger than we ever believed possible. We have this day to make it count in so many ways. My purpose is to help you prioritize your dreams, center your wellness and break your limiting beliefs. Are you ready to realize a vision bigger than yourself? Are you ready to step, step, jump for your soul?

These excerpts are from Annabel Quintero’s book, “Step Step Jump: Transforming Trauma to Triumph from the 46th Floor.” Her book is available for purchase at amazon.com. Watch a video from Quintero and learn more at stepstepjump.com.

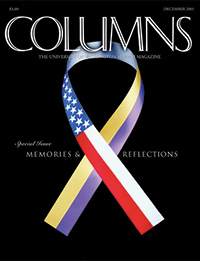

Memories and reflections

The December 2001 edition of UW Magazine’s predecessor, Columns, was largely devoted to coverage of the 9/11 attacks and the tragic plane crash that killed 16 UW alumni and Husky football fans the following day. Stories included:

The December 2001 edition of UW Magazine’s predecessor, Columns, was largely devoted to coverage of the 9/11 attacks and the tragic plane crash that killed 16 UW alumni and Husky football fans the following day. Stories included:

- 9/11: What we saw, what we felt, what it means

- Minoru Yamasaki, ’34, was the man who designed the Towers

- 9/12/2001: Remember the Huskies

- Editor’s letter: Amid tragedy, a ribbon of hope

Previous Columns pieces also include a remembrance on the 10-year anniversary in 2011 and The agony of September 12, editor Jon Marmor’s 2019 reflection on the crash that occurred on Sept. 12, 2001.

Pictured at top: Lights shine in memory of the victims of the 9/11 attacks on the anniversary in 2010. (Roverny/Wikimedia Commons)